The Virgin and Saint Vincent, 16th century tapestry stolen from a church in Roda de Isábena, a tiny town in the high Pyrenees, in 1979 was officially returned to Spain on Wednesday, April 17th, in a ceremony at the Spanish’s ambassador’s residence in Washington, D.C. U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) Director John Morton and Spanish Ambassador Ramón Gil-Casares spoke at the ceremony, describing the recovery operation as a fine example of what can be accomplished when law enforcement collaborates even across national boundaries.

This was certainly a joint effort, starting with the Spanish Civil Guard and coming to fruition in the United States. The stolen tapestry was first identified by a curator at a museum in Lérida when he saw it in an auction catalogue from the Brussels Antiques and Fine Art Fair of January 2010. The Spanish authorities contacted the Belgian police who investigated the tapestry and found that it was co-owned by a Belgian gallery owner and two partners in Milan and Paris. They found the owners had shopped the piece around to various galleries since 2008.

For reasons that are not clear to me but probably have something to do with auction houses being, on the whole, fairly amoral organizations, the discovery of the tapestry did not stop the sale. It went ahead in April of 2010. The tapestry sold for $369,000 to a dealer in Houston. That’s when Spain turned to the United States for help in stopping this sick cycle of fencing stolen goods. They invoked the Mutual Legal Assistance Treaty and after an investigation, ICE’s Homeland Security Investigations (HSI) special agents in Houston seized the tapestry in November of 2012.

There was never any doubt that this was the tapestry stolen in December of 1979 from the Cathedral of St. Vincent Martyr of Roda de Isábena. It’s a wool-silk weave depicting three saints – Saint Ramón, Saint Vincent and Saint Valerius — paying homage to the Virgin Mary and Christ child. Saint Valerius was bishop of Zaragoza in the late 3rd, early 4th century. Saint Vincent was his deacon. They were both tortured under Diocletian (a gridiron was reputedly involved) and died at Roman hands. Relics of Saints Vincent and Valerius are still kept at the cathedral in Roda.

There was never any doubt that this was the tapestry stolen in December of 1979 from the Cathedral of St. Vincent Martyr of Roda de Isábena. It’s a wool-silk weave depicting three saints – Saint Ramón, Saint Vincent and Saint Valerius — paying homage to the Virgin Mary and Christ child. Saint Valerius was bishop of Zaragoza in the late 3rd, early 4th century. Saint Vincent was his deacon. They were both tortured under Diocletian (a gridiron was reputedly involved) and died at Roman hands. Relics of Saints Vincent and Valerius are still kept at the cathedral in Roda.

Saint Ramón was bishop of Roda-Barbastre from 1104 until his death in 1126. He’s the one who commissioned the building of the Romanesque Cathedral we see today (with many later additions). His remains were buried in a beautiful sarcophagus in the cathedral. All three of these saints, therefore, have strong connections to Roda and the Huesca region in general. The tapestry was commissioned to honor the town’s main religious figures and it hung above the church’s altar for nearly 500 years.

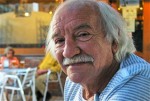

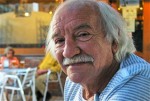

The sleepy town of Roda d’Isàvena was a county capital and seat of the diocese in Saint Ramón’s days. The episcopal see was moved to Lleida in 1149 and Roda slowly contracted from a bustling regional center to a one-horse hamlet. Today it is the smallest village in Spain to have a cathedral. This sadly made it a prime target for the depredations of Erik the Belgian, real name René Alphonse van den Berghe, an art thief who for 30 years looted museums, churches and monasteries mainly in Spain but also elsewhere in Europe.

The sleepy town of Roda d’Isàvena was a county capital and seat of the diocese in Saint Ramón’s days. The episcopal see was moved to Lleida in 1149 and Roda slowly contracted from a bustling regional center to a one-horse hamlet. Today it is the smallest village in Spain to have a cathedral. This sadly made it a prime target for the depredations of Erik the Belgian, real name René Alphonse van den Berghe, an art thief who for 30 years looted museums, churches and monasteries mainly in Spain but also elsewhere in Europe.

He was arrested in Spain in 1981 and jailed for the next four years (with a few hours’ break in 1983 when he faked a heart attack and then escaped from the hospital by literally tying his sheets together and climbing out the window; he was immediately recaptured). He was never convicted of anything, probably because during those years stolen and missing artwork just kept turning up mysteriously. In other words, he cut a deal, and now the statute of limitations has run out so he feels free to confess/brag about his exploits which, according to him, include 600 thefts of more than 6,000 artifacts — statues, paintings, tapestries, jewels, manuscripts, altarpieces, you name it.

He was arrested in Spain in 1981 and jailed for the next four years (with a few hours’ break in 1983 when he faked a heart attack and then escaped from the hospital by literally tying his sheets together and climbing out the window; he was immediately recaptured). He was never convicted of anything, probably because during those years stolen and missing artwork just kept turning up mysteriously. In other words, he cut a deal, and now the statute of limitations has run out so he feels free to confess/brag about his exploits which, according to him, include 600 thefts of more than 6,000 artifacts — statues, paintings, tapestries, jewels, manuscripts, altarpieces, you name it.

Spain was one of his favorites targets because it was packed with cultural patrimony kept in unsecured venues in small, off-the-beaten-path towns. It was easy for him to just walk in and help himself to whatever he liked. It’s hard to know what’s true or not because he’s a scumbag and proven liar, but according to interviews he’s given, much of his thieving was not just enabled but actively commissioned by church authorities. He claims whenever the Vatican wanted to convert some of their clutter into cash, they’d sell it to him and call it stolen in public.

Apparently he prided himself on selecting artifacts based on their beauty rather than their monetary value. Not that that inspired him to treat them with due reverence. One of the objects he stole from Roda’s Cathedral of St. Vincent Martyr is the chair of Saint Ramón, a 9th century cross-frame wooden stool carved with Nordic motifs that is the oldest piece of furniture known to survive in Spain. Erik the Belgian cut it to pieces to make it easier to smuggle out of the country. Decades later, after the statute of limitations had run out, he arranged for the return of some fragments. Those are now arranged on an acrylic cross-frame structure to give visitors and pilgrims some sense of how it once looked.

Apparently he prided himself on selecting artifacts based on their beauty rather than their monetary value. Not that that inspired him to treat them with due reverence. One of the objects he stole from Roda’s Cathedral of St. Vincent Martyr is the chair of Saint Ramón, a 9th century cross-frame wooden stool carved with Nordic motifs that is the oldest piece of furniture known to survive in Spain. Erik the Belgian cut it to pieces to make it easier to smuggle out of the country. Decades later, after the statute of limitations had run out, he arranged for the return of some fragments. Those are now arranged on an acrylic cross-frame structure to give visitors and pilgrims some sense of how it once looked.

As he tells the story, the chair was burned by his men when he was being tortured by the cops in 1982 and they mailed the fragments to the Ministry of Culture, but from what I can tell from news articles, as late as the mid-1990s the chair was in parts unknown. The remains don’t look scorched at all either. It’s probably just another one of his tall tales, like when he says he broke into Yuste Monastery, where Holy Roman Emperor Charles V moved to after his abdication in 1556 until his death in 1558, stripped it completely bare of all its valuables and then had sex with his girlfriend on Charles’s bed.

As he tells the story, the chair was burned by his men when he was being tortured by the cops in 1982 and they mailed the fragments to the Ministry of Culture, but from what I can tell from news articles, as late as the mid-1990s the chair was in parts unknown. The remains don’t look scorched at all either. It’s probably just another one of his tall tales, like when he says he broke into Yuste Monastery, where Holy Roman Emperor Charles V moved to after his abdication in 1556 until his death in 1558, stripped it completely bare of all its valuables and then had sex with his girlfriend on Charles’s bed.

I suppose we should be happy The Virgin and Saint Vincent tapestry is still in one piece and, uhh, unstained. Conservators will double-check on that score. The tapestry will be kept at the Institute of Cultural Heritage of Spain (IPCE), a center for restoration with the latest technology and experts in the field. It will be examined and analyzed in great detail to see if it requires any interventions to keep it from deteriorating any further and to determine the optimal conditions for its long-term preservation.

Since that picture’s a little blurry, here’s some B-roll from the ceremony that shows the tapestry being carried into the room in a crate, then unrolled and displayed.

The Sacrifice of Polyxena, the 1647 painting by Charles Le Brun that was discovered in the Coco Chanel Suite in Paris’ Ritz Hotel during renovations last year, was bought at auction by the Metropolitan Museum of Art for $1,885,194, three times the high estimate. It’s new world record for a Le Brun painting. There are very few museums that have the kind of acquisition budget that will keep them in the bidding when prices get to this level, so it’s extremely fortunate for the public that the Met was in it to win it.

The Sacrifice of Polyxena, the 1647 painting by Charles Le Brun that was discovered in the Coco Chanel Suite in Paris’ Ritz Hotel during renovations last year, was bought at auction by the Metropolitan Museum of Art for $1,885,194, three times the high estimate. It’s new world record for a Le Brun painting. There are very few museums that have the kind of acquisition budget that will keep them in the bidding when prices get to this level, so it’s extremely fortunate for the public that the Met was in it to win it. spectacular The Abduction of the Sabine Women which is one of two paintings on the subject done by the master. (The other one is in The Louvre.)

spectacular The Abduction of the Sabine Women which is one of two paintings on the subject done by the master. (The other one is in The Louvre.)