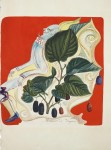

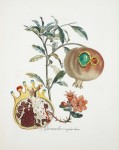

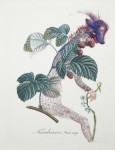

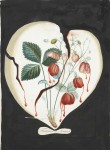

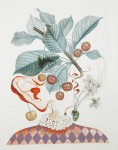

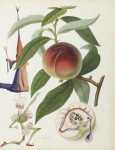

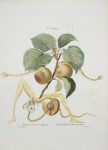

In 1969, Swiss publisher Jean Schneider commissioned Salvador Dalí to make something new and exciting out of 19th century botanical illustrations. The Surrealist artist took ten images from Pierre-Antoine Poiteau’s Pomologie française: recueil des plus beaux fruits cultivés en France (originally published in 1808; Dalí probably used the 1848 edition) and three from Traité des arbres et arbustes que l’on cultive en France by Duhamel du Monceau, illustrations by Pierre-Jean Redouté. He painted over and around the engravings with watercolors, using an element of the original prints as a jumping off point for his characteristically whimsical, sexual, humorous, orthogonal-to-reality vision.

As he later declared, in connection with his designs for jewellery, ‘I see the human form in trees, leaves, animals; the animal and vegetable in the human. My art in paint, diamonds, rubies, pearls, emeralds, gold, chrysoprase shows the metamorphosis that takes place; human beings create and change. When they sleep, they change totally into flowers, plants, trees. In Heaven comes the new metamorphosis. The body becomes whole again and attains perfection.’ (quoted in Dalí Jewels: A Collection of the Gala-Salvador Dalí Foundation, Milan, 1999, p. 36).

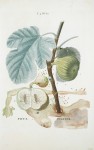

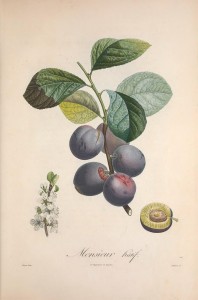

Here’s an example of that metamorphosis he describes. The original is Monsieur hâtif by Pierre-Jean Redouté. Dalí transforms the scientifically rigorous 200-year-old botanical image into Prunier hâtif, meaning Hasty plum.

This short Bonhams video describing the series superimposes the modifications over the originals so you can see the transformation in action.

Schneider published the paintings in a lithograph series known as the FruitDalí Series which was immediately popular with art collectors. The original watercolor studies, on the other hand, went into hiding. Schneider stashed them in a bank vault and they remained there unknown for decades. With the exception of a single exhibition in an art gallery Cologne in late 2000, early 2001, the watercolors have never even been seen. The gallery purchased the watercolors on consignment from Schneider and the current owner bought them from the gallery.

The fourteen watercolors were sold at Bonhams’ Impressionist and Modern Art sale in London on June 18th not as a single lot but as individuals. They went for well above their estimates; the total price paid for all 14 was £726,700 ($1,120,000).