A New York Appellate Court has ruled that the small gold cuneiform tablet looted from Berlin’s Vorderasiatisches Museum at the end of World War II and acquired by Reuven Flamenbaum after his liberation from Auschwitz must be returned to the museum. It took the court less than a month to announce its decision which sides firmly with the plaintiff rejecting all the defendants’ legal arguments.

A New York Appellate Court has ruled that the small gold cuneiform tablet looted from Berlin’s Vorderasiatisches Museum at the end of World War II and acquired by Reuven Flamenbaum after his liberation from Auschwitz must be returned to the museum. It took the court less than a month to announce its decision which sides firmly with the plaintiff rejecting all the defendants’ legal arguments.

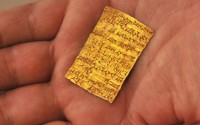

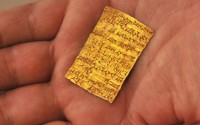

Quick summary (read last month’s entry for the full background): The tablet was discovered in the foundations of the Ishtar temple by a German archaeological team in 1913. The 9.5-gram card is inscribed in cuneiform on both sides describing the construction of the temple and calling on all who visit the temple to honor its builder, King Tukulti-Ninurta I (1243-1207 B.C.). After complications and delays caused by the First World War, the artifacts made it into the Vorderasiatisches Museum’s collection in 1926. With another war looming in 1939, the museum closed its doors and put everything in storage. Sometime between then and the end of the war when inventory was taken, the tablet went missing. Overwhelmed by the sheer numbers of artifacts looted from the museum and the conflicting authorities of post-war Berlin, the museum did not report the loss to the police or any art theft registries.

According to Flamenbaum family lore, Reuven got the tablet from a Soviet soldier around that time. He traded it for two cigarettes or a salami (the details are hazy, obviously) and took it with him when he immigrated to the United States in 1949. He settled in Long Island and got a job at a liquor store. Later he bought said liquor store using the tablet as collateral for a loan. In 1954 he had it appraised at Chritie’s and they told him it was a fake worth a hundred bucks at most. Still he kept it as a treasured memento of his survival.

Reuven Flamenbaum died in 2003. Three years later, Hannah Flamenbaum, Reuven’s daughter and executor of his estate submitted a list of assets as part of a petition to settle the account. The tablet was not mentioned individually on this list, just a “coin collection.” Her brother Israel objected that the so-called coin collection was more valuable than Hannah had stated “and includes one item identified as a ‘gold wafer’ which is believed to be an ancient Assyrian amulet and the property of a museum in Germany.” He told the Vorderasiatisches Museum about it too, while he was at it.

Reuven Flamenbaum died in 2003. Three years later, Hannah Flamenbaum, Reuven’s daughter and executor of his estate submitted a list of assets as part of a petition to settle the account. The tablet was not mentioned individually on this list, just a “coin collection.” Her brother Israel objected that the so-called coin collection was more valuable than Hannah had stated “and includes one item identified as a ‘gold wafer’ which is believed to be an ancient Assyrian amulet and the property of a museum in Germany.” He told the Vorderasiatisches Museum about it too, while he was at it.

The museum filed a claim to recover the tablet. At a Nassau County Surrogate’s Court hearing, Dr. Beate Salje, director of the Vorderasiatisches, testified that the piece was stolen at the end of the war by a person or persons unknown. The Red Army looted the museum — many of those artifacts were returned by the Soviets in 1957 — as did German troops and people taking refuge in the museum. The museum also submitted a report by Dr. Eckart Frahm, Assistant Professor of Assyriology at Yale University, covering a 1983 article by A.K. Grayson about the fate of the Ashur artifacts. This article stated that Professor H.G. Guterbock from the Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago told the author that he had seen a gold Assyrian tablet from a Berlin museum “in the hands of a dealer in New York in 1954.”

There is a reference to that allegation in the Vorderasiatisches’ record of the tablet, an annotation that it was “seen by Guterbach 1954 in New York” with “Grayson” written underneath. This entry is not dated and could have been written at any time after 1983, or before, I guess, if you suppose that Grayson heard the story from Guterbock whenever and told the museum. There’s zero evidence of that, however, so it’s meaningless speculation.

The Surrogate’s Court decided that the museum had met its burden of proving legal title, but that its claim was barred by the doctrine of laches, a legal principle that requires an owner “exercise reasonable diligence to locate” lost property. Apparently the court thought that note was evidence that the museum knew about the tablet’s being in New York decades ago but didn’t pursue it. It’s really not, though. They seriously misread the report.

The museum appealed and Hannah Flamenbaum cross-appealed, now claiming an affirmative defense that the tablet belonged to the estate based on the doctrine of laches. In May of 2012, the Appellate Division dismissed the cross-appeal and reversed the Surrogate’s Court decision on the grounds that the defense had not demonstrated that the museum failed to exercise reasonable diligence to locate the tablet. The case went back to Surrogate’s Court and finally wound up before the New York Court of Appeals last month.

The New York Court of Appeals has decided for the museum, rejecting both the doctrine of laches argument and the ugly, in my opinion, spoils of war theory which the estate proffered holding that the Soviet Union gained legal title to the tablet when it was looted as a spoil of war and then transferred the title to Reuven Flamenbaum when he bartered two cigarettes or a salami for it. They shot down both arguments in terms that made my wizened little heart grow three sizes this day:

We agree with the Appellate Division that the Estate failed to establish the affirmative defense of laches, which requires a showing “that the museum failed to exercise reasonable diligence to locate the tablet and that such failure prejudiced the [E]state” …. While the Museum could have taken steps to locate the tablet, such as reporting it to the authorities or listing it on a stolen art registry, the Museum explained that it did not do so for many other missing items, as it would have been difficult to report each individual object that was missing after the war. Furthermore, the Estate provided no proof to support its claim that, had the Museum taken such steps, the Museum would have discovered, prior to the decedent’s death, that he was in possession of the tablet …. As we observed in Lubell, in a related discussion of the defense of statute of limitations, “[t]o place a burden of locating stolen artwork on the true owner and to foreclose the rights of that owner to recover its property if the burden is not met would . . . encourage illicit trafficking in stolen art” (77 NY2d at 320). […]

The “spoils of war” theory proffered by the Estate — that the Russian government, when it invaded Germany, gained title to the Museum’s property as a spoil of war, and then transferred that title to the decedent — is rejected. The Estate’s theory rests entirely on conjecture, as the record is bereft of any proof that the Russian government ever had possession of the tablet. Even if there were such proof, we decline to adopt any doctrine that would establish good title based upon the looting and removal of cultural objects during wartime by a conquering military force …. Allowing the Estate to retain the tablet based on a spoils of war doctrine would be fundamentally unjust.

Then Hannah Flammenbaum’s attorney expressed his dismay at the ruling in terms that almost made my heart re-wizen.

Attorney Steven Schlesinger said the family was disappointed and questioned whether the court refused to uphold “title by right of conquest” because it would open the door for those who obtained art looted by Germans during the Holocaust.

“You can’t argue that the United States doesn’t recognize the right of conquest when this entire country is the result of the law of conquest,” he said, citing territorial expansion that includes Texas and California and at least 50 Indian land claims in New York.

Uh, are you seriously using the genocide of Native Americans as an argument in favor of a Holocaust survivor’s descendants getting to keep stolen property? Because that’s appalling. And yeah, actually, while we’re at it, upholding “title by right of conquest” would open the floodgates to collectors and museums keeping art looted during the Holocaust. These legal battles are ongoing. Why in the world would you want to be the case that establishes the right of Holocaust profiteers to keep the treasures they acquired with blood on their hands? All of this for a tablet that Hannah Flammenbaum claims she wants to donate to the Holocaust Museum anyway? It’s gross.

Archaeologists from the University of Münster excavating the ancient sanctuary of Jupiter Dolichenus near the town of Dülük in southern Turkey have unearthed more than 600 stamp and cylinder seals dating from between the 7th and the 4th centuries B.C. Seals were used as votive offerings to the gods and as such have been found at many ancient sanctuaries, but the sheer numbers found here make the discovery unique.

Archaeologists from the University of Münster excavating the ancient sanctuary of Jupiter Dolichenus near the town of Dülük in southern Turkey have unearthed more than 600 stamp and cylinder seals dating from between the 7th and the 4th centuries B.C. Seals were used as votive offerings to the gods and as such have been found at many ancient sanctuaries, but the sheer numbers found here make the discovery unique.  The seals are carved with a wide variety of images. They range from simple geometric shapes to scenes of heroes battling animals or mythological creatures. One seal depicts men worshiping star-like symbols of divinity.

The seals are carved with a wide variety of images. They range from simple geometric shapes to scenes of heroes battling animals or mythological creatures. One seal depicts men worshiping star-like symbols of divinity.  Shrines to Jupiter Dolichenus, who is always depicted holding a thunderbolt in one hand and a double-headed axe in the other while riding a sacred bull, have been found in Rome, Hungary, Romania, Germany, Austria and even in the remote British fort of Vindolanda just south of Hadrian’s Wall. Like Mithraism, another bull-centered Eastern mystery religion, the worship of Jupiter Dolichenus was popular in the Roman army, but it wasn’t restricted to military. Judging from handy lists of adherents that have been found inscribed in some of the 17 known temples, more than 60% of the devotees were civilians.

Shrines to Jupiter Dolichenus, who is always depicted holding a thunderbolt in one hand and a double-headed axe in the other while riding a sacred bull, have been found in Rome, Hungary, Romania, Germany, Austria and even in the remote British fort of Vindolanda just south of Hadrian’s Wall. Like Mithraism, another bull-centered Eastern mystery religion, the worship of Jupiter Dolichenus was popular in the Roman army, but it wasn’t restricted to military. Judging from handy lists of adherents that have been found inscribed in some of the 17 known temples, more than 60% of the devotees were civilians.  The seals that have been found long predate the Roman era of Jupiter Dolichenus, however. Like all the Eastern religions that carved a niche out for themselves in Rome, this Jupiter was a syncretized version of a much older deity. He started off as the Hittite sky and storm god Tesub-Hadad and was only blended with the Greco-Roman sky and storm god after the Romans conquered the area in 64 B.C. Most of what we know of this cult is post-Roman, so such a large number of seals from when he was Tesub-Hadad rather than Jupiter are invaluable sources for researchers. So far, archaeologists have identified seals from the Neo-Babylonian, local Syrian, Levantine and Achaemenid periods.

The seals that have been found long predate the Roman era of Jupiter Dolichenus, however. Like all the Eastern religions that carved a niche out for themselves in Rome, this Jupiter was a syncretized version of a much older deity. He started off as the Hittite sky and storm god Tesub-Hadad and was only blended with the Greco-Roman sky and storm god after the Romans conquered the area in 64 B.C. Most of what we know of this cult is post-Roman, so such a large number of seals from when he was Tesub-Hadad rather than Jupiter are invaluable sources for researchers. So far, archaeologists have identified seals from the Neo-Babylonian, local Syrian, Levantine and Achaemenid periods.