A mummy that has been in the collection of the Bavarian State Archaeological Collection in Munich has been identified as a young Inca woman whose skull was smashed shortly before death. When the mummy came to the museum from the Anatomical Institute of Ludwig-Maximilians University in 1970, all documentation of its origin was lost. It was first recorded at the university in 1904, but its movements before then were unknown. Because of the mummy’s dark brown skin, it was thought to be a bog body, possibly recovered from the Dachauer moor outside of Munich. The plaited hair, the fetal position (minus the lower legs which were damaged by bombing in World War II), the well-preserved bone tissue all argued against a central European bog origin, however.

A mummy that has been in the collection of the Bavarian State Archaeological Collection in Munich has been identified as a young Inca woman whose skull was smashed shortly before death. When the mummy came to the museum from the Anatomical Institute of Ludwig-Maximilians University in 1970, all documentation of its origin was lost. It was first recorded at the university in 1904, but its movements before then were unknown. Because of the mummy’s dark brown skin, it was thought to be a bog body, possibly recovered from the Dachauer moor outside of Munich. The plaited hair, the fetal position (minus the lower legs which were damaged by bombing in World War II), the well-preserved bone tissue all argued against a central European bog origin, however.

The mummy has been on display at the State Archaeological Collection since the donation. To finally identify the mummy’s origin, physical condition and cause of death, the museum decided to do a full forensic anthropological examination. They took CT scans of the entire body, did stable and unstable isotope analysis of the teeth, examined tissue samples microscopically, tested ancient DNA and reconstructed any injuries found.

Radiocarbon dating found the mummy dates to 1451–1642 A.D. and was between 20 and 25 years old at the time of death. Stable isotope analysis revealed that she ate maize and seafood and was from the Peruvian/Northern Chilean border along the coast. Her hair was dark in life (it has faded over the centuries) and her braids are tied with fiber bundles made from wavy camelid hair, a pattern characteristic of New World camelids (alpacas or llamas). Her skull also testifies to her origin: she has a Wormian or “Inca” bone at her occiput, an extra wedge of bone between sutures that is found in native South American populations but not European ones, and the flattened back of her skull is typical of Inca intentional cranial deformation.

Radiocarbon dating found the mummy dates to 1451–1642 A.D. and was between 20 and 25 years old at the time of death. Stable isotope analysis revealed that she ate maize and seafood and was from the Peruvian/Northern Chilean border along the coast. Her hair was dark in life (it has faded over the centuries) and her braids are tied with fiber bundles made from wavy camelid hair, a pattern characteristic of New World camelids (alpacas or llamas). Her skull also testifies to her origin: she has a Wormian or “Inca” bone at her occiput, an extra wedge of bone between sutures that is found in native South American populations but not European ones, and the flattened back of her skull is typical of Inca intentional cranial deformation.

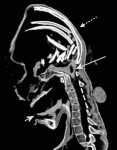

It was the skull that held the biggest surprise. She lost her front teeth after death and there’s a small wound on her forehead, but other than that, from the outside, the head looks intact. The CT scans revealed impressions are vastly deceiving. She was a victim of massive blunt force trauma to the skull. her forehead, upper skull and face were completely staved in. The upper jaw was broken. Large chunks of bone are lying against the back of the skull, along with the remains of brain tissue and possible sites of blood accumulation.

It was the skull that held the biggest surprise. She lost her front teeth after death and there’s a small wound on her forehead, but other than that, from the outside, the head looks intact. The CT scans revealed impressions are vastly deceiving. She was a victim of massive blunt force trauma to the skull. her forehead, upper skull and face were completely staved in. The upper jaw was broken. Large chunks of bone are lying against the back of the skull, along with the remains of brain tissue and possible sites of blood accumulation.

This was a perimortem injury, inflicted around the time of death, not damage done to the body after death. Terrace-like shapes on the inside back of the skull suggest a rounded weapon was used to beat her face in by someone standing in front of her. How she might have encountered this brutal skull-collapsing fate is unclear. Ritual murder is one possible explanation, but without a burial context, it’s probably unprovable. Osteological evidence suggests she lived fairly well — her dental wear was low and her joints and vertebra show no sign of stressful labor — but she was ill. Thickening of some of her heart and large intestine tissue and DNA found in rectal tissue indicate she suffered from a chronic parasitic infection by the protozoan Trypanosoma cruzi, known as Chagas disease, since infancy. Perhaps her lifetime debilitating illness made her a candidate for sacrifice. If she’s going to die anyway, goes the logic, might as well give her demise religious significance.

This was a perimortem injury, inflicted around the time of death, not damage done to the body after death. Terrace-like shapes on the inside back of the skull suggest a rounded weapon was used to beat her face in by someone standing in front of her. How she might have encountered this brutal skull-collapsing fate is unclear. Ritual murder is one possible explanation, but without a burial context, it’s probably unprovable. Osteological evidence suggests she lived fairly well — her dental wear was low and her joints and vertebra show no sign of stressful labor — but she was ill. Thickening of some of her heart and large intestine tissue and DNA found in rectal tissue indicate she suffered from a chronic parasitic infection by the protozoan Trypanosoma cruzi, known as Chagas disease, since infancy. Perhaps her lifetime debilitating illness made her a candidate for sacrifice. If she’s going to die anyway, goes the logic, might as well give her demise religious significance.

As far as how she got from Peru to Germany, researchers believe the mummy was one of two brought to Germany by Princess Theresa von Bayern of Bavaria at the turn of the century. Princess Theresa was the daughter of Prince Regent Luitpold who ruled Bavaria while King Ludwig II, the great palace builder sometimes known as Ludwig the Mad, was sidelined by purported mental illness. In her youth she and her cousin Otto, Ludwig’s brother and successor, were in love but could not marry because of Otto’s own struggles with mental illness and the political complications of her father being regent. She never married, dedicating her life to educating herself (women were not allowed to attend university) in the natural sciences.

As far as how she got from Peru to Germany, researchers believe the mummy was one of two brought to Germany by Princess Theresa von Bayern of Bavaria at the turn of the century. Princess Theresa was the daughter of Prince Regent Luitpold who ruled Bavaria while King Ludwig II, the great palace builder sometimes known as Ludwig the Mad, was sidelined by purported mental illness. In her youth she and her cousin Otto, Ludwig’s brother and successor, were in love but could not marry because of Otto’s own struggles with mental illness and the political complications of her father being regent. She never married, dedicating her life to educating herself (women were not allowed to attend university) in the natural sciences.

In 1898, Princess Theresa went on an expedition to Peru. According to her records, she carried two mummies with her back to Bavaria. There are no records of where she installed the mummies. She died in 1925, leaving her extensive collection of South American anthropological remains to the State Museum of Ethnology in Munich. Since this mummy appears in the Anatomical Institute records in 1904, just six years after her Peruvian expedition, if it was one of the Princess Theresa mummies, she probably donated it to them directly.