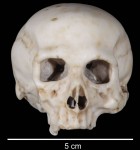

A new study provides fresh evidence that a small anatomical model of a skull was made by Leonardo da Vinci. Since the 1990s, the model has been examined by doctors, art historians and geologists, among others, who have provided solid evidence in favor of the attribution, but Belgian researcher Stefaan Missinne’s take on it contributes highly significant additional information, including for the first time a date of ca. 1508.

A new study provides fresh evidence that a small anatomical model of a skull was made by Leonardo da Vinci. Since the 1990s, the model has been examined by doctors, art historians and geologists, among others, who have provided solid evidence in favor of the attribution, but Belgian researcher Stefaan Missinne’s take on it contributes highly significant additional information, including for the first time a date of ca. 1508.

[Names have been edited per comment from Dr. Missinne below.] Winfried and Waltraud Rolshausen came across the piece in an antiques shop in Homburg, Germany, in 1987. Winfried is a medical doctor, so they purchased the skull for 600 German marks ($415 by today’s conversion) and he put it on display in his office. In 1996, Prof. Dr. Roger Saban of Paris, then director of the museum housing the massive anatomical collection of Paris Descartes University’s medical school, recognized that it was not just a decorative sculpture, but a remarkably accurate 1/3rd scale anatomical model of a skull. Saban’s conclusion:

“A striking, unusual and rare fact for a sculptor to create this very precise, proportional 1/3 scale model, which breathes a scientific spirit wanting to conserve a three-dimensional piece, which is easier to transport in secrecy than a human skull originating from a burial site or an exploration.”

Secrecy was essential for anatomists since human dissection was against the law and custom, and Leonardo was a pioneering anatomist. Saban noted the skull model bears a remarkable similarity to one of the seminal images in the history of anatomy: Leonardo da Vinci’s 1498 drawing of a sectioned cranium, now in the Royal Collection at Windsor Castle. The Windsor skull drawings on three pages, back and front, are groundbreaking innovations in anatomical illustration. RL 19059 recto was probably the first of the series (although we can’t be certain because Leonardo’s notebooks were dismembered and sold off piecemeal), and he helpfully dated it to April 2, 1498. RL 19058 and RL 19057 follow. They were Leonardo’s first forays into accurate observation-based views of human anatomy (or at least the first known to have survived), and the first anatomical drawings to employ the kind of section views used in architectural design.

Secrecy was essential for anatomists since human dissection was against the law and custom, and Leonardo was a pioneering anatomist. Saban noted the skull model bears a remarkable similarity to one of the seminal images in the history of anatomy: Leonardo da Vinci’s 1498 drawing of a sectioned cranium, now in the Royal Collection at Windsor Castle. The Windsor skull drawings on three pages, back and front, are groundbreaking innovations in anatomical illustration. RL 19059 recto was probably the first of the series (although we can’t be certain because Leonardo’s notebooks were dismembered and sold off piecemeal), and he helpfully dated it to April 2, 1498. RL 19058 and RL 19057 follow. They were Leonardo’s first forays into accurate observation-based views of human anatomy (or at least the first known to have survived), and the first anatomical drawings to employ the kind of section views used in architectural design.

Like the miniature model, the skull on the verso (back) of RL 19057 has no lower jaw and depicts the outer features of the skull at the same level of knowledge. Both are missing the inferior orbital fissure, and both place the sutura coronalis — a connective tissue joint that separates the front and back bones of the skull — in an unusual position at the back of the skull; other features on the cheekbones and eye sockets match as well.

Like the miniature model, the skull on the verso (back) of RL 19057 has no lower jaw and depicts the outer features of the skull at the same level of knowledge. Both are missing the inferior orbital fissure, and both place the sutura coronalis — a connective tissue joint that separates the front and back bones of the skull — in an unusual position at the back of the skull; other features on the cheekbones and eye sockets match as well.

There’s also a philosophical commonality between the drawings and model. According to the notes accompanying the drawings, Leonardo was studying the skull in an attempt to locate the sensus communis, the place where all the senses, all intellectual and creative faculties, come together in the brain. That spot, Leonardo theorized, was the locus of the soul. He points to the spot in the recto of RL 19058. It’s where all the lines intersect in the plane he has tilted so the seat of the soul could be seen best.

The model, which is not anatomically accurate on the inside because for structural purposes it couldn’t be as hollow as the skull actually is, does include the optic canals, the openings through which the eyes send visual information to the sensus communis where the optic nerve picks up the info and sends it to the brain. Thus the optic canals are the means by which “the visual power passes to the sensorium,” as Leonardo put it. No other skull known includes this morphological detail linked to the sensus communis.

The model, which is not anatomically accurate on the inside because for structural purposes it couldn’t be as hollow as the skull actually is, does include the optic canals, the openings through which the eyes send visual information to the sensus communis where the optic nerve picks up the info and sends it to the brain. Thus the optic canals are the means by which “the visual power passes to the sensorium,” as Leonardo put it. No other skull known includes this morphological detail linked to the sensus communis.

What Saban got wrong is the material. He thought it was carved out of marble. A 2003 X-ray fluorescence analysis found that the skull was made of an “agate alabaster” extracted from the Cipollone mine just 50 miles from Florence. Missinne found an anomaly in the results: the presence of the rare metallic element iridium which does not naturally occur in alabaster from the Cipollone mine or anywhere else that we know of. That means the iridium was added, and that the skull wasn’t carved so much as modeled, created out of a mixture of ground agate, calcium and river sand (the source of the Ir) that Leonardo called “mistioni.” This was his own invention, the product of research between 1503 and 1508 mentioned in several of his surviving notebooks. He made artificial pearls with this modelling material, and in Manuscript F and the Codex Atlanticus he writes that he can use it to produce agate. That’s as close to a signature as we’re likely to get.

There are references to model skulls in Leonardo collections after his death. The first is a “detailed engraved skull made from fine calcedonia stone” listed in the 1524 inventory of Leonardo’s student and heir (and possible lover) Andrea Salai. A 1584 catalog of the Villa Riposo in Florence describes one object as “by Leonardo da Vinci there’s a skull of a dead man with all its minutiae.” There are also descriptions of a model of “a child’s skull” in a Habsburg collection in Prague and Innsbruck, which could be an interim step between its Florentine origin and rediscovery nearly 500 years later in southwestern Germany.

Read about Leonardo’s anatomical drawings in the Windsor collection in this catalog from the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s 1981 exhibition of the Windsor drawings, Leonardo da Vinci: Nature Studies. The entire book is available free of charge to view online or download as a pdf.

Reference: Missinne, S.J. (2014). The oldest anatomical handmade skull of the world c. 1508: ‘The ugliness of growing old’ attributed to Leonardo da Vinci, Wiener Medizinische Wochenschrift. The full paper can be purchased or accessed via institutional login here.