After more than a dozen years, a sailor’s coat that was recovered from the gun turret of the Civil War ironclad warship USS Monitor is about to go on public display. Conserving this compelling artifact was an incredibly hard task, starting with the act of removing it from the ship. The 150-ton revolving gun turret, a revolutionary innovation that made a strong impression with its two massive Dahlgren artillery guns manned by 14 sailors but that was problematic in practice, was raised from the protected wreck site on August 5th, 2002. It was found inverted as it had flipped upside-down when the ship capsized and the skeletal remains of two crewmen were buried under coal, assorted debris and the Dahlgren guns.

After more than a dozen years, a sailor’s coat that was recovered from the gun turret of the Civil War ironclad warship USS Monitor is about to go on public display. Conserving this compelling artifact was an incredibly hard task, starting with the act of removing it from the ship. The 150-ton revolving gun turret, a revolutionary innovation that made a strong impression with its two massive Dahlgren artillery guns manned by 14 sailors but that was problematic in practice, was raised from the protected wreck site on August 5th, 2002. It was found inverted as it had flipped upside-down when the ship capsized and the skeletal remains of two crewmen were buried under coal, assorted debris and the Dahlgren guns.

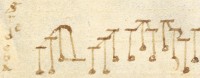

Amidst that debris was a wet mass of fabric wrapped around a group of gun tools including a rammer and a worm (a device used to clean unspent powder from the barrel). It was heavily concreted, part of a hardened mass of iron corrosion salts, marine life and sediment that formed over the 141 years the wreck spent under 220 feet of salt water. The concretion had grown into the woven fiber of fabric, and removing the textile from so firm an embrace required painstakingly precise use of hand and pneumatic chisels. It took days of work just to dislodge it.

Amidst that debris was a wet mass of fabric wrapped around a group of gun tools including a rammer and a worm (a device used to clean unspent powder from the barrel). It was heavily concreted, part of a hardened mass of iron corrosion salts, marine life and sediment that formed over the 141 years the wreck spent under 220 feet of salt water. The concretion had grown into the woven fiber of fabric, and removing the textile from so firm an embrace required painstakingly precise use of hand and pneumatic chisels. It took days of work just to dislodge it.

That was just the beginning. We have very few textiles recovered from shipwrecks as they tend to decay quickly in the ocean water, so there isn’t exactly a manual of how to go about preserving a Civil War-era wool coat pried out of the jaws of an iron-clad gun turret. Conservators next placed it in a long, leisurely fresh water bath to slowly leach the ocean minerals out of the fabric. It would take many, many more baths over the next decade plus. In between soakings, conservators worked on cleaning the concretions still on the surface and interior of the coat using ultrasonic dental scalers. Then they worked on removing the rust stains.

That was just the beginning. We have very few textiles recovered from shipwrecks as they tend to decay quickly in the ocean water, so there isn’t exactly a manual of how to go about preserving a Civil War-era wool coat pried out of the jaws of an iron-clad gun turret. Conservators next placed it in a long, leisurely fresh water bath to slowly leach the ocean minerals out of the fabric. It would take many, many more baths over the next decade plus. In between soakings, conservators worked on cleaning the concretions still on the surface and interior of the coat using ultrasonic dental scalers. Then they worked on removing the rust stains.

They found that although the very fine merino-type wool was still in surprisingly pliable condition, the cotton threads that had stitched the sections together were long gone. Add to that the stress from the wreck and ocean living and the garment had come apart into 180 pieces. An estimated 85-90% of it had survived but far from intact, and there was no chance it could be completely stitched back together because the fabric was just too fragile.

Textile conservators Colleen Callahan and Newbold Richardson reached out to the museum and conservation community to see if anybody could recognize the garment from the pieces. Karen France, Chief Curator of the Navy Museum, identified it as a double-breasted sack jacket known as a “pilot’s jacket.” The Monitor‘s may be the only one of its kind to have survived. It was privately made and then modified for military use. Black rubber buttons marked “U.S.N” over two stars and an anchor that had come off when the cotton string fixing them to the coat rotted away, were found next to the coat.

Textile conservators Colleen Callahan and Newbold Richardson reached out to the museum and conservation community to see if anybody could recognize the garment from the pieces. Karen France, Chief Curator of the Navy Museum, identified it as a double-breasted sack jacket known as a “pilot’s jacket.” The Monitor‘s may be the only one of its kind to have survived. It was privately made and then modified for military use. Black rubber buttons marked “U.S.N” over two stars and an anchor that had come off when the cotton string fixing them to the coat rotted away, were found next to the coat.

Callahan and Richardson worked hard to piece together some of the 180 fragments so that they could be mounted on archival backing and arranged for display in a way that made it look like a proper coat even if still in pieces.

Following a trail of evidence left by residual stains, stitching holes and the weave of the fabric, Richardson reassembled the front and back panels of the coat, while Callahan worked on the sleeves.

“It was like a jigsaw puzzle,” Callahan says, “and even after all our work we could not find a place for every piece.”

Now fully laid out on their protective mounts, the sections of the coat look much as they might have before being assembled by their original maker.

Six long-separated black rubber buttons bearing the letter “U.S.N.”and an anchor have been reunited with the fabric, fastened down through hidden magnets.

Part of an iron handle from a gunnery tool remains embedded in the cloth, too, left to preserve both the fragile weave and a dramatic part of the Monitor’s story.

“What better way to tell the story of the ship’s sinking — and to put people back in that exact moment of time — than a coat that was discarded by someone trying to escape the turret,” Hoffman says.

Conservators have freeze-dried the coat pieces to remove the last water still in the textile from the many baths and now they are ready for display at the USS Monitor Center.