The Victorian-era public urinal atop Blackboy Hill in Bristol has been listed as Grade II historic structures of “more than special interest” by English Heritage.

A spokesman for the organisation said: “Historic elements of the public realm, including street furniture and public facilities, are particularly vulnerable to damage, alteration and removal and where they survive well, they will in some cases be given serious consideration for designation.

A spokesman for the organisation said: “Historic elements of the public realm, including street furniture and public facilities, are particularly vulnerable to damage, alteration and removal and where they survive well, they will in some cases be given serious consideration for designation.

“In times of austerity, facilities and structures such as this set of urinals are under increasing threat, and where there are found to be deserving of protection English Heritage will recommend to the Secretary of State that they be added to the National Heritage List for England.”

He said the urinal was a “relatively rare surviving example of a once common type of building” and represented the “civic aspirations of the authorities in the Bristol suburbs in the late Victorian period”.

The ornate cast iron building was made by W MacFarlane & Co. Ltd’s Saracen Foundry in Glasgow, by order of the Bristol Sanitary Committee in the 1880s. It is a rectangular full height structure with intricate perforated designs in Moorish style on the iron walls and a glass roof. Inside, chest-high white porcelain urinals are inset in the iron framing with curved modesty screens dividing each unit. The tile floor is a modern replacement, but the rest is original. The facility is still in use today and is a little the worse for wear. Perhaps its listing will inspire renovations.

The ornate cast iron building was made by W MacFarlane & Co. Ltd’s Saracen Foundry in Glasgow, by order of the Bristol Sanitary Committee in the 1880s. It is a rectangular full height structure with intricate perforated designs in Moorish style on the iron walls and a glass roof. Inside, chest-high white porcelain urinals are inset in the iron framing with curved modesty screens dividing each unit. The tile floor is a modern replacement, but the rest is original. The facility is still in use today and is a little the worse for wear. Perhaps its listing will inspire renovations.

Public lavatories were a nexus of Victorian obsessions — sanitation, technology, decoration as a marker of respectability, social reform, class conflict, gender roles, avoiding the various grossnesses of human biology. The modern era of public toilets was ushered in by sanitary engineer George Jennings who built “commodious refreshment rooms, with the accompaniments usually connected with them at large railway stations” in the Crystal Palace for the Great Exhibition of 1851. The euphemistic description in the catalog was no deterrent to use. The first public flushing toilets were a hit, used 827,820 times by men and women during the five months of the Great Exhibition. The pay toilets raised £2,441 at a penny per usage, a fee that would remain standard for 150 years, inflation be damned. The idiom for urinating “spend a penny” is a legacy of Jennings’ innovation.

Public lavatories were a nexus of Victorian obsessions — sanitation, technology, decoration as a marker of respectability, social reform, class conflict, gender roles, avoiding the various grossnesses of human biology. The modern era of public toilets was ushered in by sanitary engineer George Jennings who built “commodious refreshment rooms, with the accompaniments usually connected with them at large railway stations” in the Crystal Palace for the Great Exhibition of 1851. The euphemistic description in the catalog was no deterrent to use. The first public flushing toilets were a hit, used 827,820 times by men and women during the five months of the Great Exhibition. The pay toilets raised £2,441 at a penny per usage, a fee that would remain standard for 150 years, inflation be damned. The idiom for urinating “spend a penny” is a legacy of Jennings’ innovation.

Spurred by the success of the Exhibition facilities and George Jennings’ ceaseless advocacy for public lavatories, the Society of Arts privately funded separate men and women’s toilets in 1852. They were as spectacular a failure as the ones in the Crystal Palace had been a success. Elegantly appointed and staffed by a supervisor and two attendants, these bathrooms were pricey at two pence per use or three pence for the basic plus a wash and brush (that’s right, you had to pay extra to wash your hands after using the public toilet). Perhaps deterred by the price or simply resistant to the very notion, only 58 men and 24 women used the lavatories over the course of a month. The facilities were promptly shut down.

The first public in both senses of the word — municipally funded and located on the public thoroughfare — lavatory was built outside the Royal Exchange in 1855. It was for men only and facilities would remain exclusively Gents for nearly 40 years. There was immense resistance from both men and women to the notion of public conveniences for the fairer sex. For some people, the notion of women peeing or pooping in close confines with other people of all walks of life was shockingly immodest, by its very design putting respectable middle and upper class women in the position of exposing their bodies and bodily functions in public much like prostitutes. The mixing of classes was seen as a danger in and of itself, the lady contaminated by rubbing shoulders with the flower girl.

The Ladies Sanitary Association began campaigning for public women’s facilities in 1878, demanding there be public restrooms (with one free water closet in every facility for poor women) to accommodate the hundreds of thousands of working women navigating the city. Eleven years later, the first municipal women’s facility opened in Piccadilly Circus.

The controversy was by no means over, however. In London’s civil parish of St Pancras, the first public latrines with accommodations for women were built on Kentish Town Road and St Pancras Road in the 1890s, but when the Vestry (the parish government) debated installing a women’s only facility at the intersection of Park Street and Camden High Street, it took five years, from 1900 to 1905, to get over all the snickering and dissembling from the governing body and protests from the residents and businesspeople. We have no less of a witness to this fracas than playwright George Bernard Shaw who was a Vestryman at St Pancras from 1897 to 1903.

In the March 1909 issue The Englishwoman, a journal advocating the extension of the franchise to women, Shaw published The Unmentionable Case for Woman’s Suffrage, an essay arguing that women in government were necessary to keep grown men from devolving into junior high nitwits whenever issues pertaining to women’s sanitation, public accommodations, etc. were discussed. He also revealed the sabotage and Catch 22s that kept the bathrooms from being built for five years.

For instance, the bus companies protested that the facility would be a dangerous traffic obstacle, even though there was a men’s room literally in the middle of the intersection across the street from the proposed ladies’ room. They put up a wooden model at the proposed location and indeed it was ploughed into no less than 45 times. Shaw pointed out in the essay that this statistic was not exactly bullet-proof.

For instance, the bus companies protested that the facility would be a dangerous traffic obstacle, even though there was a men’s room literally in the middle of the intersection across the street from the proposed ladies’ room. They put up a wooden model at the proposed location and indeed it was ploughed into no less than 45 times. Shaw pointed out in the essay that this statistic was not exactly bullet-proof.

[The wooden model] brought about all the power of the vestryman over the petty commerce and petty traffic of his district. In one day, every omnibus on the Camden Town route, every tradesman’s cart owned within a radius of two miles, and most of the rest of the passing vehicles, including private carriages driven to the spot on purpose, crashed into that obstruction with just violence enough to produce an accident without damage. The drivers who began the game were either tipped or under direct orders; but the joke soon caught on, and was kept up for fun by all and sundry.

The one Vestrywoman, Mrs. Miall-Smith, tried to get her colleagues to take the issue seriously because the thousands of women flocking to Camden Town to work in its factories needed to pee every once in a while, but with the class-mixing paranoia that accompanied the public toilet issue, her argument wasn’t likely to persuade the opposition.

Shaw noted that there was one highly relevant woman staff member who should have weighed in on the issue: a female sanitation inspector hired to examine the sanitary accommodations for women factory workers. She had an enormous task of inspecting work sites to see if they even had any facilities for women at all (many of them did not) and checking the ones that did have women’s lavatories multiple times a week for cleanliness. Shaw’s comment on her is a fascinating window into the complexities of communication across class and gender lines in Victorian Britain.

The exclusion of women from the Borough Council left the inspectress in a difficult position. The barrier of the unmentionable arose between her and members of the Health Committee. It was all the higher because the inspectress was generally an educated woman of university rank, not at all conversant with the sort of local tradesman who regards the subject of sanitary accommodation as one to which no lady should allude in the presence of a gentleman.

Finally in December of 1905, the debate ended. After more prodding from Mrs. Miall-Smith and a report from the Highways, Sewers and Public Works Committee, the borough agreed to build the Park Street women’s lavatory.

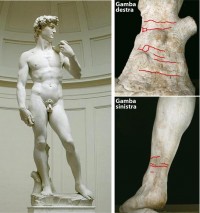

The Chianti region of Tuscany has experienced more than 250 tremors in three days, the two strongest of which measured 3.8. and 4.1 on the Richter scale. They only visible harm they caused was some minor structural damage in a town 20 miles south of Florence, but authorities are concerned that this could presage a larger seismic event that would wreak havoc on the city’s greatest artistic icon: Michelangelo’s statue of David.

The Chianti region of Tuscany has experienced more than 250 tremors in three days, the two strongest of which measured 3.8. and 4.1 on the Richter scale. They only visible harm they caused was some minor structural damage in a town 20 miles south of Florence, but authorities are concerned that this could presage a larger seismic event that would wreak havoc on the city’s greatest artistic icon: Michelangelo’s statue of David.  Small cracks in the left ankle and stump were first noticed in 1851. They may have developed during the flood of 1844 or three years later when sculptor Clemente Papi made a full-size plaster cast of David, but the recent study suggests the original source of the problem was that the statue spent almost four centuries outside the Palazzo della Signoria leaning forward at an approximately five degree angle which put undue stress on the weakest parts of the structure. (The angled placement wasn’t deliberate; researchers believe it was likely the result of the ground settling unevenly underneath the plinth.) The tilt was only corrected when David was moved indoors to the Galleria dell’Accademia in 1873.

Small cracks in the left ankle and stump were first noticed in 1851. They may have developed during the flood of 1844 or three years later when sculptor Clemente Papi made a full-size plaster cast of David, but the recent study suggests the original source of the problem was that the statue spent almost four centuries outside the Palazzo della Signoria leaning forward at an approximately five degree angle which put undue stress on the weakest parts of the structure. (The angled placement wasn’t deliberate; researchers believe it was likely the result of the ground settling unevenly underneath the plinth.) The tilt was only corrected when David was moved indoors to the Galleria dell’Accademia in 1873.