The Batmobile made for the 1966 TV show from a 1955 Lincoln Futura concept car by legendary car customizer George Barris may be the one we think of as the first Batmobile, but that’s just because the TV show was such a smash hit (pow! bam!) and the car so damn cool that it became an instant icon. Its iconic status garnered it $4.62 million including buyer’s premium when it sold at auction in January of 2013, and I myself repeatedly referred to it as the first Batmobile.

I was wrong. It’s the first of a long line of sublime to ridiculous television and film custom Batmobiles (the 1940s serials used a black Cadillac, a limo and a Mercury Eight, all off the line), but National Periodic Publications, owners of DC Comics, officially licensed a Batmobile built years before the TV show for promotional purposes. Its design comes straight from the comic book, a particularly great one at that, a product of the vision of artist Dick Sprang.

I was wrong. It’s the first of a long line of sublime to ridiculous television and film custom Batmobiles (the 1940s serials used a black Cadillac, a limo and a Mercury Eight, all off the line), but National Periodic Publications, owners of DC Comics, officially licensed a Batmobile built years before the TV show for promotional purposes. Its design comes straight from the comic book, a particularly great one at that, a product of the vision of artist Dick Sprang.

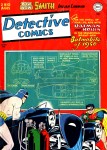

Dated February 1950, Detective Comics #156 hit the newsstands in December 1949 (spanning two decades!) and introduced a new Batmobile for a new decade. The story is that Batman is chasing mobster Smiley Dix when the bridge he’s driving over collapses. Batman breaks his leg and the Batmobile is totalled. Our hero takes advantage of his convalescence to build a new Batmobile — stronger, faster, and full of new bells and whistles. The “Batmobile of 1950” was high-tech marvel with a radar antenna in the tail fin and a forensic laboratory in place of a back seat. It made an indelible impression on Batman fans, many of whom consider it the definitive design to this day.

Dated February 1950, Detective Comics #156 hit the newsstands in December 1949 (spanning two decades!) and introduced a new Batmobile for a new decade. The story is that Batman is chasing mobster Smiley Dix when the bridge he’s driving over collapses. Batman breaks his leg and the Batmobile is totalled. Our hero takes advantage of his convalescence to build a new Batmobile — stronger, faster, and full of new bells and whistles. The “Batmobile of 1950” was high-tech marvel with a radar antenna in the tail fin and a forensic laboratory in place of a back seat. It made an indelible impression on Batman fans, many of whom consider it the definitive design to this day.

Forrest Robinson was 13 years old when Detective Comics #156 was issued, and it certainly made an impression on him. For years he sketched ideas for a real Batmobile in his notebook. Ten years later, he bought a 1956 Oldsmobile Rocket 88 and designed a new look for it inspired by Sprang’s Batmobile. It took Robinson and his friend Len Perham three years of work in the Robinson family barn in New Hampshire to replace the Oldsmobile body with a custom fiberglass body 17 feet long and seven feet wide with the iconic single giant dorsal fin, an upturned bat-nose front, quad headlights, horizontal tailfins and doors that slide into pockets on the rear fenders. In 1963 the car was done. Robinson painted it space-age silver and drove it as his personal ride.

Forrest Robinson was 13 years old when Detective Comics #156 was issued, and it certainly made an impression on him. For years he sketched ideas for a real Batmobile in his notebook. Ten years later, he bought a 1956 Oldsmobile Rocket 88 and designed a new look for it inspired by Sprang’s Batmobile. It took Robinson and his friend Len Perham three years of work in the Robinson family barn in New Hampshire to replace the Oldsmobile body with a custom fiberglass body 17 feet long and seven feet wide with the iconic single giant dorsal fin, an upturned bat-nose front, quad headlights, horizontal tailfins and doors that slide into pockets on the rear fenders. In 1963 the car was done. Robinson painted it space-age silver and drove it as his personal ride.

In 1966, the popularity of the Batman television program caused a Batmania throughout the land. The All Star Dairy Association, a national dairy co-op, spent $3 million to tap into this groundswell, licensing Batman, Robin and the Batmobile from National Periodic Publications for use in dairy-based promotional campaigns. They sold Batnog that Christmas and a variety of fruit drinks, ice cream, cones, sandwiches, etc. with Batman and Robin on the packaging. (Slam Bang Vanilla Ice Cream with Banana Marshmallow needs to make a comeback, by the way. It should never have left us.) It worked like a charm. By early 1967, sales on Batman-packaged ice creams increased 300%.

In 1966, the popularity of the Batman television program caused a Batmania throughout the land. The All Star Dairy Association, a national dairy co-op, spent $3 million to tap into this groundswell, licensing Batman, Robin and the Batmobile from National Periodic Publications for use in dairy-based promotional campaigns. They sold Batnog that Christmas and a variety of fruit drinks, ice cream, cones, sandwiches, etc. with Batman and Robin on the packaging. (Slam Bang Vanilla Ice Cream with Banana Marshmallow needs to make a comeback, by the way. It should never have left us.) It worked like a charm. By early 1967, sales on Batman-packaged ice creams increased 300%.

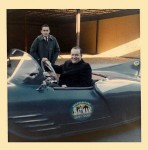

All Star’s New Hampshire affiliate, Green Acres Ice Cream, leased Robinson’s car to play to make personal appearances as the Batmobile. They repainted it in Batman black, put the Batman Dairy Foods logo on the doors and under the dorsal fin, and drove it around three northeastern states promoting Batman & Robin ice cream products. This was the first ever officially licensed touring Batmobile. George Barris’ Batmobiles, the Futura and its fiberglass-on-Ford-Galaxie copies, didn’t start touring until 1967.

All Star’s New Hampshire affiliate, Green Acres Ice Cream, leased Robinson’s car to play to make personal appearances as the Batmobile. They repainted it in Batman black, put the Batman Dairy Foods logo on the doors and under the dorsal fin, and drove it around three northeastern states promoting Batman & Robin ice cream products. This was the first ever officially licensed touring Batmobile. George Barris’ Batmobiles, the Futura and its fiberglass-on-Ford-Galaxie copies, didn’t start touring until 1967.

After its turn selling ice cream to the kiddies, Forrest Robinson sold the car for $200 to a friend of his in 1967. The friend didn’t show the car much love, I’m afraid, and it spent decades rusting in a New Hampshire field before passing through several hands until it was acquired in 2011 by Florida car collector George Albright. He researched its history, contacting Robinson, Perham and dairy executives who remembered its service as the Batmobile. Not having the time and resources to dedicate to a proper restoration of the vehicle, in 2013, a month after the Barris Batmobile made such a splash at auction, he put it up for sale on eBay with a minimum bid of $19,800. He wound up pulling it and doing a private deal, selling it for an undisclosed amount to Toy Car Exchange LLC who have spent the past year restoring it to pristine condition. Thanks to the addition of red accents, it looks more Batmanny than it ever did.

After its turn selling ice cream to the kiddies, Forrest Robinson sold the car for $200 to a friend of his in 1967. The friend didn’t show the car much love, I’m afraid, and it spent decades rusting in a New Hampshire field before passing through several hands until it was acquired in 2011 by Florida car collector George Albright. He researched its history, contacting Robinson, Perham and dairy executives who remembered its service as the Batmobile. Not having the time and resources to dedicate to a proper restoration of the vehicle, in 2013, a month after the Barris Batmobile made such a splash at auction, he put it up for sale on eBay with a minimum bid of $19,800. He wound up pulling it and doing a private deal, selling it for an undisclosed amount to Toy Car Exchange LLC who have spent the past year restoring it to pristine condition. Thanks to the addition of red accents, it looks more Batmanny than it ever did.

Toy Car Exchange has now put the restored 1963 Batmobile for sale at Heritage Auctions’ Entertainment & Music Memorabilia auction on December 6th. The opening bid is $90,000.