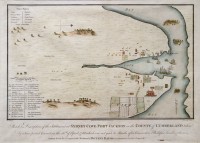

Documents discovered in the archives of the Spanish navy reveal that Spain planned to invade the nascent British colony in Australia in the mid-1790s. Chris Maxworthy, vice president of the Australian Association for Maritime History (AAMH), found the documents detailing a plan of attack approved by King Carlos IV to fire “hot shot” cannons, cannons that fired heated balls that could set wooden ships and buildings on fire as well as blow large holes in them, on Port Jackson, modern-day Sydney Harbour.

“The plan was to attack Sydney from the Spanish colonies in South America with a fleet of 100 medium-sized boats armed with cannons and ‘hot shot’,” [Maxworthy] told The Australian Financial Review.

“The goal was the complete surrender by the British and their expulsion from the Australian land mass … The effect [of the hot shot] would be to not only impact the targets ashore but also create multiple fires in the wooden buildings of that era in Sydney, particularly if the plans occurred during the hot summer months.”

Governor Arthur Phillip had established the first British colony on the continent at Port Jackson in January of 1788, 18 years after explorer James Cook landed there and named the harbour after Admiralty official Sir George Jackson. The convicts started coming right away, as the prisoner transport system to Britain’s colonies had been painfully cut off since 1776 by the Revolutionary War and subsequent independence. By 1792, there were more than 4,000 convicts populating Sydney, but since food was scarce and disease was rife, they would not have been able to put up much of a fight against a Spanish armada. Any Spanish victory would likely have been of short duration, however, as Britain had a much stronger navy and army and could have reclaimed the colony with minimal effort.

Governor Arthur Phillip had established the first British colony on the continent at Port Jackson in January of 1788, 18 years after explorer James Cook landed there and named the harbour after Admiralty official Sir George Jackson. The convicts started coming right away, as the prisoner transport system to Britain’s colonies had been painfully cut off since 1776 by the Revolutionary War and subsequent independence. By 1792, there were more than 4,000 convicts populating Sydney, but since food was scarce and disease was rife, they would not have been able to put up much of a fight against a Spanish armada. Any Spanish victory would likely have been of short duration, however, as Britain had a much stronger navy and army and could have reclaimed the colony with minimal effort.

Spain’s concern was that a British colony in the Pacific would be a grave threat to the crown’s holdings in South America and the Philippines, a concern first articulated by Spanish naval officer Francisco Muñoz y San Clemente only months after the colony was founded. He reported that the convict colonists would be well positioned to act as privateers and harry Spanish shipping between the Philippines and the Americas. Once it had developed a full naval presence, the Australia colony would be able to launch a full-scale invasion of Spain’s holdings.

That same year, 1788, Italian nobleman, explorer and Spanish naval officer Alessandro Malaspina and José de Bustamante y Guerra proposed a Pacific expedition modeled after Cook’s. The government approved the expedition and each man had a corvette custom-built for the voyage. It also added a stop to the expedition’s itinerary: Port Jackson, so the explorers could see first hand how valid Muñoz’s concerns were.

That same year, 1788, Italian nobleman, explorer and Spanish naval officer Alessandro Malaspina and José de Bustamante y Guerra proposed a Pacific expedition modeled after Cook’s. The government approved the expedition and each man had a corvette custom-built for the voyage. It also added a stop to the expedition’s itinerary: Port Jackson, so the explorers could see first hand how valid Muñoz’s concerns were.

Bustamante and Malaspina departed from Cadiz in 1789. Over the next five years, they traveled from the east coast of South America around Cape Horn to the west coast and up north to Mexico, then detoured to Alaska on orders to search yet again for the mythical Northwest Passage. From Alaska they went back to Mexico, then west to Manila and south to Doubtful Sound on New Zealand’s South Island. In March of 1793, the expedition landed at Port Jackson where they mapped the coast and studied the local flora and fauna.

Malaspina confirmed Muñoz’s impressions in his report to the crown. Port Jackson was indeed a danger to Spain’s overseas possessions because

Malaspina confirmed Muñoz’s impressions in his report to the crown. Port Jackson was indeed a danger to Spain’s overseas possessions because

with the greatest ease a crossing of two or three months through healthy climates, and a secure navigation, could bring to our defenceless coasts two or three thousand castaway bandits to serve interpolated with an excellent body of regular troops. It would not be surprising that in this case — the women also sharing the risks as well as the sensual pleasures of the men — the history of the invasions of the Huns and Alans in the most fertile provinces of Europe would be revived in our surprised colonies. … The pen trembles to record the image, however distant, of such disorders.

All those prostitutes, forgers and pickpockets wouldn’t just band up with the regular troops to make a formidable invasion force, but then they’d settle down and have lots of reproductive sex just like those German barbarian ancestors of the British monarch did.

Despite the trembling of his pen, Malaspina did not advocate a military response to this threat. He believed the worst case scenario could be prevented by opening trade between Chile, the Philippines and Sydney. Why fight lusty convicts when you can do business with them and make it very much in their interest not to interrupt the flow of Chilean beef and Philippine spices? Malaspina had witnessed firsthand how hard-scrabble an existence the colonists eked out. They had little livestock, pulled their own carts and plows, and rarely ate meat. Spanish products would prove addictive, he thought, and instead of spending money trying to squash the colony, the crown would profit handsomely while achieving its ultimate goal of defanging the Australian menace.

From Port Jackson, Malaspina and Bustamante made one last stop — Tonga — before returning to Cadiz in September of 1794. King Charles IV and Manuel de Godoy, the king’s prime minister and puppet master (and probably the queen’s lover), welcomed Malaspina back, promoting him to fleet-brigadier for his efforts. The good vibes didn’t last. In late 1795 Malaspina was caught conspiring to overthrow Godoy and the next year was tried for plotting against the state. Although the trial did not result in a conviction, in April of 1796 Charles IV stripped him of his naval rank and sent him to jail in the fortress of San Antón in La Coruña, Galicia, where he remained imprisoned until 1802.

From Port Jackson, Malaspina and Bustamante made one last stop — Tonga — before returning to Cadiz in September of 1794. King Charles IV and Manuel de Godoy, the king’s prime minister and puppet master (and probably the queen’s lover), welcomed Malaspina back, promoting him to fleet-brigadier for his efforts. The good vibes didn’t last. In late 1795 Malaspina was caught conspiring to overthrow Godoy and the next year was tried for plotting against the state. Although the trial did not result in a conviction, in April of 1796 Charles IV stripped him of his naval rank and sent him to jail in the fortress of San Antón in La Coruña, Galicia, where he remained imprisoned until 1802.

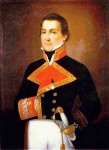

Bustamante did not share in his colleague’s disgrace. He was promoted to navy brigadier after their return and remained in the crown’s good graces. In 1795, Spain was compelled to declare war on Great Britain by its ally France. Even if Malaspina hadn’t gotten on Godoy’s shitlist, his proposal for a mercantile approach to Australia wasn’t suited to the new circumstances. Instead, in 1796 Bustamante was appointed governor of Paraguay and Commander General of the fleet of Río de la Plata, in charge of the military defense of Spain’s South American colonies, and, as we now know, a pre-emptive military attack on Port Jackson.

The archival documents show that Jose de Bustamante y Guerra, the deputy commander of the Spanish expedition, subsequently proposed an invasion of the colony to King Carlos IV and his ministers. The government sent Bustamante to a new military post at Montevideo in Uruguay and he began to build a small fleet of attack vessels.

“As the military and naval commander, Bustamante was tasked to both defend South America from an anticipated British invasion, and to take the fight to the British in the Pacific,” Mr Maxworthy said.

Although Spain remained a French ally and enemy of Britain until the Battle of Trafalgar turned the tide on October 21st, 1805, neither side ever did get around to invading each others’ colonies. When Godoy switched allegiance to Great Britain after Trafalgar and then back to France after Napoleon’s defeat of Prussia in 1807, it made King Charles IV look like even more of a weakling than everyone (including court painter Francisco de Goya who consistently depicted him as a rotund, confused country squire better suited to hunting than absolute rule) already thought he was.

Although Spain remained a French ally and enemy of Britain until the Battle of Trafalgar turned the tide on October 21st, 1805, neither side ever did get around to invading each others’ colonies. When Godoy switched allegiance to Great Britain after Trafalgar and then back to France after Napoleon’s defeat of Prussia in 1807, it made King Charles IV look like even more of a weakling than everyone (including court painter Francisco de Goya who consistently depicted him as a rotund, confused country squire better suited to hunting than absolute rule) already thought he was.

Charles’ son Ferdinand favored an alliance with Britain and after one attempted coup by the Crown Prince and several riots by his supporters, on March 19th, 1808, King Carlos IV abdicated in favor of his son who became King Ferdinand VII.