CAT scans on 30 of the recently restored plaster casts of people killed in the eruption of Vesuvius in 79 A.D. have found that Pompeiians had far better teeth than their modern counterparts. The scans showed the victims’ teeth were in excellent condition (the orthodontist who analyzed the scans called their teeth “perfect”) without a single cavity among them. There was some evidence of wear, but no tooth decay whatsoever.

CAT scans on 30 of the recently restored plaster casts of people killed in the eruption of Vesuvius in 79 A.D. have found that Pompeiians had far better teeth than their modern counterparts. The scans showed the victims’ teeth were in excellent condition (the orthodontist who analyzed the scans called their teeth “perfect”) without a single cavity among them. There was some evidence of wear, but no tooth decay whatsoever.

The sample is too small to draw broad conclusions about the dental health of the overall population of the city, but that they ate healthy high-fiber foods low in fat and sugar is in keeping with what we know of their diet from previous poop studies. There’s another reason for their fine teeth: samples of Pompeii’s water and air found high levels of fluoride. Volcanic rocks and hot springs are high in fluorine which dissolves into water as fluoride, the same thing 25 countries deliberately add to their tap water for public dental health purposes.

The sample is too small to draw broad conclusions about the dental health of the overall population of the city, but that they ate healthy high-fiber foods low in fat and sugar is in keeping with what we know of their diet from previous poop studies. There’s another reason for their fine teeth: samples of Pompeii’s water and air found high levels of fluoride. Volcanic rocks and hot springs are high in fluorine which dissolves into water as fluoride, the same thing 25 countries deliberately add to their tap water for public dental health purposes.

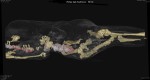

While the casts have been X-rayed before, this is the first time any of them have been CAT scanned. One of the reasons for that is that the density of the plaster varies — the oldest of it dates to the 19th century, plus layers from subsequent restorations — but it can be as dense as bone. People with our squishy outsides are comparatively easy to scan, but add a thick plaster exoskeleton and it gets tricky. The archaeological team was able to borrow a 16-layer scanner from Philips SpA Healthcare that allowed them to see through the plaster to the bones in great detail. The scanner is superfast, taking only 100 seconds for a full body scan, and is able to block distortions to the images caused by metal elements. It was designed for people with prosthetics or implanted devices. The dead of Pompeii don’t have titanium hips and pacemakers, but metal pieces were added to some of the casts to reinforce the plaster structure.

While the casts have been X-rayed before, this is the first time any of them have been CAT scanned. One of the reasons for that is that the density of the plaster varies — the oldest of it dates to the 19th century, plus layers from subsequent restorations — but it can be as dense as bone. People with our squishy outsides are comparatively easy to scan, but add a thick plaster exoskeleton and it gets tricky. The archaeological team was able to borrow a 16-layer scanner from Philips SpA Healthcare that allowed them to see through the plaster to the bones in great detail. The scanner is superfast, taking only 100 seconds for a full body scan, and is able to block distortions to the images caused by metal elements. It was designed for people with prosthetics or implanted devices. The dead of Pompeii don’t have titanium hips and pacemakers, but metal pieces were added to some of the casts to reinforce the plaster structure.

The aperture of the scanner is just 70 cm (28 inches), so they had to select smaller casts that would fit all the way through, or limit the scan to the head and chest. The 30 casts of men, women and one child, plus two more casts of animals (a dog and a pig or wild boar) were CAT scanned. The mother holding her child discovered under the staircase in the House of the Golden Bracelet, for example, could not be scanned, but a slighter older child, probably a boy, found a few yards away from the mother was small enough to be fully scanned. The cast of the child contained a full skeleton. The length of femur established that the child was between two and three years old at time of death. A bump on the sternum previously thought to be a knot has now been identified as a fibula, probably gold, a baby version of the heavy gold bracelet found on his mother’s wrist which gave the house its name.

The aperture of the scanner is just 70 cm (28 inches), so they had to select smaller casts that would fit all the way through, or limit the scan to the head and chest. The 30 casts of men, women and one child, plus two more casts of animals (a dog and a pig or wild boar) were CAT scanned. The mother holding her child discovered under the staircase in the House of the Golden Bracelet, for example, could not be scanned, but a slighter older child, probably a boy, found a few yards away from the mother was small enough to be fully scanned. The cast of the child contained a full skeleton. The length of femur established that the child was between two and three years old at time of death. A bump on the sternum previously thought to be a knot has now been identified as a fibula, probably gold, a baby version of the heavy gold bracelet found on his mother’s wrist which gave the house its name.

The scans also found fractured cranial bones, indicating that some of the deaths believed to have been caused by asphyxia from volcanic gases were in fact the result of victims being struck hard on the head by falling roof tiles or rocks.

The scans also found fractured cranial bones, indicating that some of the deaths believed to have been caused by asphyxia from volcanic gases were in fact the result of victims being struck hard on the head by falling roof tiles or rocks.

Another fascinating find was actually the lack of a find. The cast of a woman thought from her silhouette to have been pregnant at the time of her death is empty. The CAT scan found no fetal bones and no adult bones. This is an artifact from the 19th century when some of the early casts were done after the skeletal remains were removed, possibly for ethical or religious reasons. One of the most iconic casts, the dog writhing on its back from the House of Orpheus, is also completely devoid of bones and it’s unlikely they would have been removed out of respect for the dead.

Another fascinating find was actually the lack of a find. The cast of a woman thought from her silhouette to have been pregnant at the time of her death is empty. The CAT scan found no fetal bones and no adult bones. This is an artifact from the 19th century when some of the early casts were done after the skeletal remains were removed, possibly for ethical or religious reasons. One of the most iconic casts, the dog writhing on its back from the House of Orpheus, is also completely devoid of bones and it’s unlikely they would have been removed out of respect for the dead.

The analysis of the scans is still in the beginning stages so we’ll hear more about this project as it progresses. They have collected sufficient data to create 3D virtual models that will not only provide invaluable information about the lives and deaths of the people of Pompeii, but also about the plaster itself which will be of great aid in future conservation decisions. The team is planning to create a database of the 3D models so scholars around the world have access to them.

The analysis of the scans is still in the beginning stages so we’ll hear more about this project as it progresses. They have collected sufficient data to create 3D virtual models that will not only provide invaluable information about the lives and deaths of the people of Pompeii, but also about the plaster itself which will be of great aid in future conservation decisions. The team is planning to create a database of the 3D models so scholars around the world have access to them.