Five dwellings and one laundry facility at the ancient site of Pompeii have been reopened to the public after an extensive program of restoration: the House of the Cryptoporticus, the House of Paquius Proculus, the House of Sacerdos Amandus, the House of Fabius Amandio, the House of the Ephebus and the Fullonica (laundry) of Stephanus. The restorations were part of the EU-funded Great Pompeii Project, created to address the precipitous decline of the UNESCO World Heritage Site, which focuses on repairing the most significant and at-risk structures. Work was taking so long that in October the EU threatened to pull funding if they didn’t get cracking, which is why the announcement that these six major restorations have been completed was made with much fanfare two months later.

Five dwellings and one laundry facility at the ancient site of Pompeii have been reopened to the public after an extensive program of restoration: the House of the Cryptoporticus, the House of Paquius Proculus, the House of Sacerdos Amandus, the House of Fabius Amandio, the House of the Ephebus and the Fullonica (laundry) of Stephanus. The restorations were part of the EU-funded Great Pompeii Project, created to address the precipitous decline of the UNESCO World Heritage Site, which focuses on repairing the most significant and at-risk structures. Work was taking so long that in October the EU threatened to pull funding if they didn’t get cracking, which is why the announcement that these six major restorations have been completed was made with much fanfare two months later.

The House of the Cryptoporticus is a lavishly decorated building complete with a luxurious four-room bath complex. In its heyday it was part of one of the largest homes in Pompeii which was divided in two around 20 years before the apocalypse. Eighteen women and children fled to what they hoped was safety in the House of the Cryptoporticus during the 79 A.D. eruption of Vesuvius. Unfortunately there was no such thing as safety in Pompeii that day and they all fell victim to the volcano’s wrath. It was also severely damaged during Allied bombing in 1943, particularly the peristyle (quadrangular garden).

The House of the Cryptoporticus is a lavishly decorated building complete with a luxurious four-room bath complex. In its heyday it was part of one of the largest homes in Pompeii which was divided in two around 20 years before the apocalypse. Eighteen women and children fled to what they hoped was safety in the House of the Cryptoporticus during the 79 A.D. eruption of Vesuvius. Unfortunately there was no such thing as safety in Pompeii that day and they all fell victim to the volcano’s wrath. It was also severely damaged during Allied bombing in 1943, particularly the peristyle (quadrangular garden).

The frescoed walls and mosaic floors of the cryptoporticus (exterior covered passageway), the bathing rooms, the summer triclinium (dining room) and the oecus (main hall or salon) have been restored. A fresco in the peristyle that managed to survive World War II in relatively decent condition has been returned to its former splendor. It’s a religious shrine, a lararium, with a portrait of Hermes in a niche to the left where offerings would be left. A large looping snake dominates the wall. It is surrounded by green boughs. A beautiful peacock and a small altar with a snake wound around it complete the picture.

The frescoed walls and mosaic floors of the cryptoporticus (exterior covered passageway), the bathing rooms, the summer triclinium (dining room) and the oecus (main hall or salon) have been restored. A fresco in the peristyle that managed to survive World War II in relatively decent condition has been returned to its former splendor. It’s a religious shrine, a lararium, with a portrait of Hermes in a niche to the left where offerings would be left. A large looping snake dominates the wall. It is surrounded by green boughs. A beautiful peacock and a small altar with a snake wound around it complete the picture.

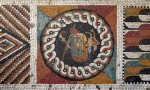

The House of Paquius Proculus is known for its electoral graffiti, one of which gives the house its name. It’s not a large home, but it has some of the most beautiful mosaic floors in the city. Black-and-white and color mosaics adorn the floor of the atrium with scenes of animals and geometric borders.

The House of Paquius Proculus is known for its electoral graffiti, one of which gives the house its name. It’s not a large home, but it has some of the most beautiful mosaic floors in the city. Black-and-white and color mosaics adorn the floor of the atrium with scenes of animals and geometric borders.  A black dog chained to a door bares its teeth on the floor of the entryway to dissuade any who would step foot on him with malicious intent. The triclinium has lost most of its mosaic floor, but in the center is an exceptional survivor: a Nilotic panel of pygmies fishing, one of whom falls into the water where hippopotami and snapping crocodiles await him eagerly.

A black dog chained to a door bares its teeth on the floor of the entryway to dissuade any who would step foot on him with malicious intent. The triclinium has lost most of its mosaic floor, but in the center is an exceptional survivor: a Nilotic panel of pygmies fishing, one of whom falls into the water where hippopotami and snapping crocodiles await him eagerly.

The House of Sacerdos Amandus has a spectacular triclinium with floor to ceiling frescoes in the third style depicting the adventures of mythological heroes Hercules, Perseus, Odysseus, Daedalus and Icarus.

The House of Sacerdos Amandus has a spectacular triclinium with floor to ceiling frescoes in the third style depicting the adventures of mythological heroes Hercules, Perseus, Odysseus, Daedalus and Icarus.

The House of Fabius Amandus is a modest structure, a typical example of a middle class Roman home. That’s significant in and of itself, but it’s also decorated with fourth style red panels on a yellow field with architectural features and with lovely mosaic floors.

The House of Fabius Amandus is a modest structure, a typical example of a middle class Roman home. That’s significant in and of itself, but it’s also decorated with fourth style red panels on a yellow field with architectural features and with lovely mosaic floors.

The House of the Ephebus, named after the bronze statue of a youth that was once part of a fountain in the sumptuous structure. It was the home of wealthy merchants and it shows. It’s actually three houses joined into one, and is replete with high quality mosaic and fresco decorations of floors and walls. Restorers reconstructed the reclining couches of the triclinium. The summer triclinium in the garden is decorated with erotic frescoes of Egyptian theme and surrounded by columns.

The House of the Ephebus, named after the bronze statue of a youth that was once part of a fountain in the sumptuous structure. It was the home of wealthy merchants and it shows. It’s actually three houses joined into one, and is replete with high quality mosaic and fresco decorations of floors and walls. Restorers reconstructed the reclining couches of the triclinium. The summer triclinium in the garden is decorated with erotic frescoes of Egyptian theme and surrounded by columns.

The Fullonica of Stephanus was excavated from 1912 to 1914 and is a fascinating composite of private and commercial, a patrician house that was fully restructured and adapted to use as a laundry. A room west of the vestibule is decorated in brilliantly colored fourth style frescoes. Large panels of bright red with decorative borders are topped by architectural features with garlands and birds on a white background. Archaeologists believe this was the main office of the fullonica where people checked their garments in and out.

The Fullonica of Stephanus was excavated from 1912 to 1914 and is a fascinating composite of private and commercial, a patrician house that was fully restructured and adapted to use as a laundry. A room west of the vestibule is decorated in brilliantly colored fourth style frescoes. Large panels of bright red with decorative borders are topped by architectural features with garlands and birds on a white background. Archaeologists believe this was the main office of the fullonica where people checked their garments in and out.

The impluvium (the sunken pool meant to catch rain water from the open roof) in the atrium was converted into a wash tub with the addition of walls. This was likely the delicate cycle of antiquity since the tougher, dirtier, badly stained fabrics were stomped on by laundry employees in larger tubs out back. There are three large square tubs in the main laundry facility and five oval tubs. Clothes were soaked in a mixture of water and unrine. Urine with its precious ammonia was a key element in ancient cleaning. It was collected from animals and humans, harvested from public bathrooms.

The impluvium (the sunken pool meant to catch rain water from the open roof) in the atrium was converted into a wash tub with the addition of walls. This was likely the delicate cycle of antiquity since the tougher, dirtier, badly stained fabrics were stomped on by laundry employees in larger tubs out back. There are three large square tubs in the main laundry facility and five oval tubs. Clothes were soaked in a mixture of water and unrine. Urine with its precious ammonia was a key element in ancient cleaning. It was collected from animals and humans, harvested from public bathrooms.

After the fabrics soaked for a while, they were trampled by the laundry workers. Then the cloth was treated with fuller’s earth — a type of clay that served as a fabric softener — and rinsed very, very thoroughly. Garments were laid out to dry on the roof or outside the entrance before getting ironed in the fullonica’s man-sized press.

Visitors to the restored fullonica will see a demonstration of how fabrics were treated in ancient Roman laundry facilities. Special tours covering all six of the newly reopened homes will be offered from now until January 10th.