The Tarkhan Dress isn’t really a dress. It’s a linen chemise nowadays, although when it was new it may have been longer. The hem is gone so there’s no way of knowing. The garment was discovered during Sir William Matthew Flinders Petrie’s 1913 excavation of a 1st Dynasty tomb in a 5,000-year-old cemetery at Tarkhan, Egypt, 30 miles south of Cairo, only neither Flinders Petrie nor anybody else realized they had found it. Sixty-four years would pass before somebody did.

The Tarkhan Dress isn’t really a dress. It’s a linen chemise nowadays, although when it was new it may have been longer. The hem is gone so there’s no way of knowing. The garment was discovered during Sir William Matthew Flinders Petrie’s 1913 excavation of a 1st Dynasty tomb in a 5,000-year-old cemetery at Tarkhan, Egypt, 30 miles south of Cairo, only neither Flinders Petrie nor anybody else realized they had found it. Sixty-four years would pass before somebody did.

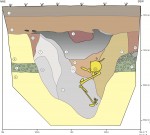

The mud-brick niched tomb had been extensively looted in antiquity. There was little left inside besides a set of alabaster jars, two wooden tool handles and pottery (which is why they dated the tomb to around 2,800 B.C.), and what Flinders Petrie described as a “great pile of linen cloth.” The pile of dirty linen went to University College London whose modest collection of Egyptian artifacts would expand by orders of magnitude when they bought Flinders Petrie’s enormous collection in 1913. The university museum is now the Petrie Museum of Egyptian Archaeology.

In 1977, the pile of “funerary rags” was sent to the Victoria and Albert Museum’s Textile Conservation Workshop for cleaning and conservation. The conservators discovered the Tarkhan Dress buried between 17 different kinds of textiles. At first they thought it was just another rag, but when they followed one seam they found another rag stitched to it, and then another. That’s when they realized those three rags were in fact a tunic with two sleeves. It was inside out and showed signs of wear, namely creases at the elbows and armpits. The v-neck linen shirt with tiny pleats on the bodice and sleeves was in excellent condition, considering its age. Conservators stitched it onto Crepeline silk so it could be placed on a dress form and displayed the way it was worn thousands of years ago.

Because of the age of the tomb in which it was discovered, the garment was hailed as Egypt’s oldest garment and the oldest woven garment in the world, but because the tomb was not intact and the linens from the burial chamber had been jumbled and dumped by looters, its context couldn’t provide a reliable date. Radiocarbon dating the garment was out of the question in 1977 because back then the test required a sample the size of a handkerchief. Some of the linen in the pile was analyzed in the early 1980s by the then-new technology of accelerator mass spectrometry carbon dating which dated it to the late third-millennium B.C., but the results were too broad to satisfy and the samples weren’t taken from the dress itself.

Last year, a tiny 2.24 milligram sample of fabric was taken from the Tarkhan Dress and radiocarbon dated at the University of Oxford. The testing found there was a 95% probability that the garment was made between 3,482 and 3,102 B.C. Modern AMS dating is usually more precise than that, but the tininess of the sample made a wider range necessary. As the 1st Dynasty is thought to have begun around 3,100 B.C., there’s a good chance the Tarkhan Dress pre-dates the Early Dynastic period and the first pharaohs to rule over a unified Egypt.

Textile fragments made of flax (Linum usitatissimum) are known from at least Egyptian Neolithic times, while weaving on horizontal looms is evidenced from at least the early fourth millennium BC. Iconographic representations in Second Dynasty Egyptian tombs at Helwan (in Greater Cairo) show the deceased wearing similar types of garments to the Tarkhan Dress, indicating that the depiction of clothing was based upon contemporary fashions rather than idealised. […]

The Tarkhan Dress … remains the earliest extant example of complex woven clothing, that is, a cut, fitted and tailored garment as opposed to one that was draped or wrapped. Along with other textile remains from Egypt, it has the potential to provide further insights into craft specialisation and the organisation of textile manufacture during the development of the world’s first territorial state

For all you sewers out there, the Petrie Museum has patterns and instructions on how to create your own Tarkhan Dress. It assumes a basic grasp of skills (like how to pleat) and terminology (what is this whip stitch you speak of?) so it’s not for beginners. Should you take the plunge, I am in a position to guarantee you one glowing blog review and probably at least a good dozen comments.