Artifacts and remains of the Wampanoag leader who forged the first alliance with the Pilgrims are being reburied in his original grave after a two-decade search for the scattered relics.

Artifacts and remains of the Wampanoag leader who forged the first alliance with the Pilgrims are being reburied in his original grave after a two-decade search for the scattered relics.

The Pilgrims called him Massasoit as if it were his first name and it has stuck, but in fact it’s a hereditary title meaning “Great Leader.” His name was Ousamequin. As Great Leader of the Pokanoket Wampanoags, he held the allegiance of numerous chieftains and villages in the Wampanoag Confederation stretching from Narragansett Bay east to Cape Cod, most of modern-day southeastern Massachusetts.

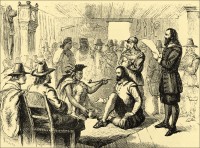

In the six years before the Mayflower landed at Plymouth, two smallpox outbreaks had decimated the Pokanoket, reducing their warrior ranks from a formidable 3,000 to a mere 300. With their enemies the Narragansetts at their doorstep (they controlled the territory west of Narragansett Bay), ready to take advantage of the Pokanoket’s military weakness, in March of 1621 Ousamequin entered into a treaty of nonaggression and mutual defense with the newly arrived English colonists. They agreed not to attack each other and to come to each other’s aid if either one were attacked by third parties.

The English had weapons and the ability to use them; the Pokanoket knew how to grow, make and find food. The military alliance was advantageous to both, since the Narragansetts were as ill-disposed towards the English as they were toward the Pokanoket, and good relations with their indigenous neighbors were essential to the survival of the colony. Without them, the Plymouth colony would quickly go the way of their countrymen at Jamestown and starve to death. As it was, they only had a place to live because they had moved into a Pokanoket village (Patuxet) left abandoned after a smallpox epidemic, and although Ousamequin didn’t know this, at the time of the alliance barely three months after their arrival, almost half of the colonists and Mayflower crew had already died from diseases contracted during the Atlantic crossing.

The English had weapons and the ability to use them; the Pokanoket knew how to grow, make and find food. The military alliance was advantageous to both, since the Narragansetts were as ill-disposed towards the English as they were toward the Pokanoket, and good relations with their indigenous neighbors were essential to the survival of the colony. Without them, the Plymouth colony would quickly go the way of their countrymen at Jamestown and starve to death. As it was, they only had a place to live because they had moved into a Pokanoket village (Patuxet) left abandoned after a smallpox epidemic, and although Ousamequin didn’t know this, at the time of the alliance barely three months after their arrival, almost half of the colonists and Mayflower crew had already died from diseases contracted during the Atlantic crossing.

The alliance lasted 40 years, ending only with Massasoit Ousamequin’s death in 1661. English sources acknowledge that the colony would almost certainly have died on the vine in those difficult first few years without his invaluable aid and recognized him as a man of unimpeachable integrity, loyalty and generosity. That didn’t stop the growing colony from encroaching ever more on Pokanoket lands, of course, and as the decades passed, the alliance became increasingly strained. Under pressure from all sides, Ousamequin chose to keep the alliance together and repeatedly sold the colonists ever-larger sections of Pokanoket territory. In 1653, he and his eldest son Wamsutta sold land known as Sowams which included most of the present-day towns of Warren and Barrington, Rhode Island, and Somerset, Massachusetts, for 35 pounds sterling. The buyers were a who’s who of early New England history: Miles Standish, Josiah Winslow, William Bradford, John Winslow, et al.

One small piece of Sowams was not part of the sale: the “neck,” meaning the uplands overlooking the bay. Called Montaup, anglicized as Mount Hope, this was Ousamequin’s hometown and was to be reserved for the Pokanoket until such time as they chose to leave. After his death, he was buried there. By the end of King Philip’s War (King Philip was the English name of Massasoit Metacom, Ousamequin’s second son, who took up arms against the Plymouth Colony in 1675 to stop their untrammeled expansionism) in 1678, the surviving Pokanoket fled to Maine and Mount Hope Neck was absorbed into Warren, Rhode Island.

One small piece of Sowams was not part of the sale: the “neck,” meaning the uplands overlooking the bay. Called Montaup, anglicized as Mount Hope, this was Ousamequin’s hometown and was to be reserved for the Pokanoket until such time as they chose to leave. After his death, he was buried there. By the end of King Philip’s War (King Philip was the English name of Massasoit Metacom, Ousamequin’s second son, who took up arms against the Plymouth Colony in 1675 to stop their untrammeled expansionism) in 1678, the surviving Pokanoket fled to Maine and Mount Hope Neck was absorbed into Warren, Rhode Island.

Neglected and unprotected, Massasoit Ousamequin’s grave was destroyed during construction of the Providence, Warren and Bristol Railroad, which opened in Warren on July 4th, 1851, 190 years after Massasoit’s death. His wasn’t the only grave on the hilltop, and souvenir hunters and archaeologists (who at this time were also largely souvenir hunters) dug up the site, collecting artifacts and human remains which wound up dispersed throughout personal collections and museums.

Neglected and unprotected, Massasoit Ousamequin’s grave was destroyed during construction of the Providence, Warren and Bristol Railroad, which opened in Warren on July 4th, 1851, 190 years after Massasoit’s death. His wasn’t the only grave on the hilltop, and souvenir hunters and archaeologists (who at this time were also largely souvenir hunters) dug up the site, collecting artifacts and human remains which wound up dispersed throughout personal collections and museums.

In 1990, the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act made it federal law that grave goods and human remains held in collections, institutions of learning and museums be returned to related tribes for reburial according to their religious traditions.

Members of the Wampanoag Nation have spent 20 years tracking down the remains and artifacts of Massasoit Ousamequin. It was their “spiritual and cultural obligation,” said Ramona Peters, who coordinated the effort. […]

Ousamequin’s artifacts include a pipe, knife, beads and arrowheads.

The Rhode Island Historical Society has repatriated about 75 items to the appropriate tribes since the law’s passage, including artifacts belong [sic] to Ousamequin. They were donated as relics in the 1800s, but collections aren’t assembled in that way today, said Kirsten Hammerstrom, director of collections.

“Grave goods are not something we dig up and accept. They belong to the tribe,” she said. […]

The Wampanoags have collected hundreds of funerary objects that were removed from the burial ground on the hill and held dozens of burials for their ancestors whose graves were disturbed, Peters said.

“It is an honor and a privilege to be able to do this for our ancestors,” she said.

Now it’s Massasoit Ousamequin’s turn.