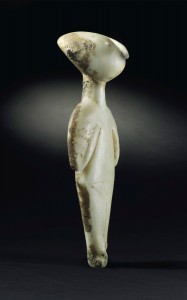

The Guennol Stargazer, an Anatolian marble idol carved in the Chalcolithic period, around 3000-2200 B.C., sold at Christie’s Exceptional Sale in New York on Friday for $14,471,500. The idol is of the Kiliya type, a stylized, geometric female figure known as “Stargazers” because their flat, wedge-shaped heads perched on slender necks give the appearance that they are looking up at the skies. They’re usually found in fragments — breaking them at the necks may have been part of a ritual burial of the figurines — and broken heads and bodies are fairly common.

The Guennol Stargazer, an Anatolian marble idol carved in the Chalcolithic period, around 3000-2200 B.C., sold at Christie’s Exceptional Sale in New York on Friday for $14,471,500. The idol is of the Kiliya type, a stylized, geometric female figure known as “Stargazers” because their flat, wedge-shaped heads perched on slender necks give the appearance that they are looking up at the skies. They’re usually found in fragments — breaking them at the necks may have been part of a ritual burial of the figurines — and broken heads and bodies are fairly common.

This example, however, is one of only about 15 complete Stargazers (it has been repaired to reattach the head to the neck), and it is widely acknowledged as the greatest of them all. She is the tallest at nine inches and is more long-limbed than her sisters, who tend towards a squatter proportion. The Schuster Stargazer, the last marble Kiliya-type idol to sell at auction, went for a bargain $1,808,000 in 2005. It’s not surprising that the Guennol Stargazer as the preeminent example of the type smashed through that ceiling. While some press outlets reported an estimated sale price of $3 million, Christie’s did not have a pre-sale estimate posted on its website like it usually does. They made one available by request only, which may be an indication that they knew the sky was the limit. Also, estimates usually rely on comparables as well as market determinations, and in terms of quality, design and provenance, the Guennol is in a category of her own.

[youtube=https://youtu.be/tqt4KcF2l_Y&w=430]

The fact that it was part of the Guennol Collection is a testament to its exceptional quality and enhances its already superlative reputation. Edith and Alastair Martin began collecting ancient works of art in 1947 when they were ensourceled into obsession by a few pieces they’d acquired. Their approach was not the usual one. They did not focus on a particular time period, geographical area or motif. They simply bought pieces that they and the experts they consulted with thought were exceptionally beautiful examples of their art. The Guennol Collection (so named because Guennol is the Welsh word for Martin, and they spent their honeymoon in Wales) was small — at around a hundred pieces — but so prestigious that the Metropolitan Museum of Art was thrilled to exhibit it in its entirety for years. Another figurine from the collection, the powerful and evocative Guennol Lioness, set a still-unbroken record for an ancient work of art when it sold in 2007 for $57.2 million. (Aww, look at my dinky old entry. And the nice picture I added just now because the original was 1) a terrible thumbnail, and 2) broken.)

There is something of a cliffhanger ending to this episode. The person who made the winning bid may or may not get his or her hands on the Stargazer after all. Culture Minister Nabi Avcı announced to the press on Friday that Turkey has opened proceedings in US court to stop the sale. The Turkish government believes the idol was unearthed in Gallipoli (Kilia, the town where the first figure of the type was found, is on the Gallipoli peninsula) and that it is therefore the legitimate owner.

Because the Martins have owned the Guennol Stargazer since 1948, comfortably before the 1970 cutoff date established by the UNESCO Convention, Turkey’s legal claim is grounded in Turkish law. There has been a law on the books since 1906, when Turkey was still the Ottoman Empire, decreeing that all antiquities discovered on private or public land are the property of the state and cannot be legally exported from the country. That decree was maintained with the adoption of the Turkish Civil Code in the newly formed Republic of Turkey in 1926. It was in effect until 1973 when a new law was written which again declared all antiquities property of the state. This was broadened in 1983 to change “antiquities” to “cultural and natural properties requiring protection.”

Because the Martins have owned the Guennol Stargazer since 1948, comfortably before the 1970 cutoff date established by the UNESCO Convention, Turkey’s legal claim is grounded in Turkish law. There has been a law on the books since 1906, when Turkey was still the Ottoman Empire, decreeing that all antiquities discovered on private or public land are the property of the state and cannot be legally exported from the country. That decree was maintained with the adoption of the Turkish Civil Code in the newly formed Republic of Turkey in 1926. It was in effect until 1973 when a new law was written which again declared all antiquities property of the state. This was broadened in 1983 to change “antiquities” to “cultural and natural properties requiring protection.”

In order to successfully pursue its case in a US court, Turkey needs to have relevant law establishing state ownership of antiquities, which it clearly has, and, the big challenge in this instance, it has to prove that the disputed artifact was unearthed within its national boundaries. The court has given Turkey 60 days to provide said proof. Minister Avcı says they have the “necessary scientific reports showing the statue belongs to Turkey” and will submit them within the two month deadline.

Meanwhile, Christie’s is enjoined from transferring the Guennol Stargazer to the buyer until the case has been decided.