Archaeologists working near Pompeii’s Porta Stabia gate have unearthed a monumental tomb with the longest funerary inscription ever discovered in the ancient city. The tomb was found by accident during maintenance and restoration work on buildings in the San Paolino area as part of the EU-funded Great Pompeii Project. A crew restoring a 19th century palazzo slated to become the new library and offices of the archaeological superintendency came across a fragment of marble while doing depth tests on the foundations. Marble is very rarely used in Pompeiian funerary monuments, so archaeologists realized immediately that this could be something special. Because a new excavation was outside the parameters of the EU funding, they had to scrounge up 200,000 euros from the regular budget to dig the find site in anticipation of discovering something of significance. They were not disappointed.

Archaeologists working near Pompeii’s Porta Stabia gate have unearthed a monumental tomb with the longest funerary inscription ever discovered in the ancient city. The tomb was found by accident during maintenance and restoration work on buildings in the San Paolino area as part of the EU-funded Great Pompeii Project. A crew restoring a 19th century palazzo slated to become the new library and offices of the archaeological superintendency came across a fragment of marble while doing depth tests on the foundations. Marble is very rarely used in Pompeiian funerary monuments, so archaeologists realized immediately that this could be something special. Because a new excavation was outside the parameters of the EU funding, they had to scrounge up 200,000 euros from the regular budget to dig the find site in anticipation of discovering something of significance. They were not disappointed.

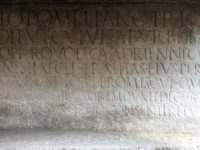

The top of the tomb was lost, likely destroyed during the construction of the palazzo in hte 19th century, but what remains is a large and imposing marble structure that is unique among Pompeiian funerary monuments. The inscription carved into the marble facade is more than four meters (13 feet) long and has seven lines eulogizing the deceased’s life and successes. He was grand even as a teenager, we are assured, when he hosted a great banquet to celerate his donning of the toga virilis (“toga of manhood”) when he was 15-17 years old. He set up no fewer than 456 triclinia (formal dining rooms) to accomodate thousands of members of the public. Not content with merely feeding everyone, he treated them to games fielding 416 gladiators. We know from inscriptions and contemporary sources that no more than 30 pairs of gladiators fought in the regular games in Pompeii, so this figure is miles out of the ordinary, the kind of spectacle you’d see in Rome, not in a modest southern Italian colony.

The top of the tomb was lost, likely destroyed during the construction of the palazzo in hte 19th century, but what remains is a large and imposing marble structure that is unique among Pompeiian funerary monuments. The inscription carved into the marble facade is more than four meters (13 feet) long and has seven lines eulogizing the deceased’s life and successes. He was grand even as a teenager, we are assured, when he hosted a great banquet to celerate his donning of the toga virilis (“toga of manhood”) when he was 15-17 years old. He set up no fewer than 456 triclinia (formal dining rooms) to accomodate thousands of members of the public. Not content with merely feeding everyone, he treated them to games fielding 416 gladiators. We know from inscriptions and contemporary sources that no more than 30 pairs of gladiators fought in the regular games in Pompeii, so this figure is miles out of the ordinary, the kind of spectacle you’d see in Rome, not in a modest southern Italian colony.

Largess is a recurring theme in the res gestae of this prominet citizen. Other subjects covered in the inscription are his wedding and its extra fancy banquet, the political and religious offices he held, the many gladiatorial games and venationes (beast hunts) he sponsored, his generous gifts of silver coin to the people and moneys in support of magistrates and guilds. He was one of the duoviri quinquennales (the two heads of the city administration elected every five years with additional powers to update the census) and was acclaimed by the people as patronus of the city, which he humbly declines in the last line of the inscription because he is unworthy of so great an hour.

Director General of the Pompeii archaeological site Massimo Osanna calls it the most important find of the last few decades, and one of the most important in the history of the site. He’s all but certain of the identity of the tomb’s occupant. The details in the biographical inscription, the luxuriousness of the monument and its location near the tombs of the Alleius family strongly suggest this was the final resting place of Gnaeus Alleius Nigidius Maius, duoviri quinquennales for 55-56 A.D. and an immensely rich and well-connected games impresario. No Pompeiian is better documented in the archaeological record. His name appears in 17 inscriptions, graffiti and edicts painted on the walls on the city.

Director General of the Pompeii archaeological site Massimo Osanna calls it the most important find of the last few decades, and one of the most important in the history of the site. He’s all but certain of the identity of the tomb’s occupant. The details in the biographical inscription, the luxuriousness of the monument and its location near the tombs of the Alleius family strongly suggest this was the final resting place of Gnaeus Alleius Nigidius Maius, duoviri quinquennales for 55-56 A.D. and an immensely rich and well-connected games impresario. No Pompeiian is better documented in the archaeological record. His name appears in 17 inscriptions, graffiti and edicts painted on the walls on the city.

One of the edicts painted on the facade of the house of A. Trebus Valens on the Via dell’Abbondanza advertises Maius’ latest gift to the people: “Twenty pairs of gladiators and their substitutes of the quinquennialis Gnaeus Alleius Nigidius Maius will fight at Pompeii. No public monies will be used.” Illustrating that any excuse will do to throw a party, another edict on the Via dell’Abbondanza announces: “For the inauguration of the paintings on wood of Gnaeus Alleius Nigidius Maius, on June 13th, there will be a parade, a hunt of wild beasts, fighters, and the velarium.” Maius died a year before the cataclysmic eruption of Vesuvius that buried Pompeii in 79 A.D.

He was very much a new man, a symbol of a society that was becoming increasingly mobile under the emperors of the 1st century. His father was a freedman who had made a fortune and had no bones about spending it on massively oversized celebrations to get his son started on a political career that would be largely based on throwing the biggest and best games in town. His humble beginnings were no deterrent to Maius’ ascent. He was a personal friend to the emperor Nero, and indeed, may have been involved in the resolution of one of Pompeii’s most explosive events before the literally explosive event that stopped the city in its tracks.

In 59 A.D., there was a giant and deadly brawl in the amphitheater between the local Pompeiians and the residents of nearby Nuceria, which had been a rival since Sulla’s conquest of Pompeii in 80 B.C. Old resentments were stirred up afresh when Nero gave some Pompeiian territories to Nuceria two years before the fight at the amphitheater. This likely played a part in things coming to blows that day, although it’s unknown exactly what sparked the conflict.

In 59 A.D., there was a giant and deadly brawl in the amphitheater between the local Pompeiians and the residents of nearby Nuceria, which had been a rival since Sulla’s conquest of Pompeii in 80 B.C. Old resentments were stirred up afresh when Nero gave some Pompeiian territories to Nuceria two years before the fight at the amphitheater. This likely played a part in things coming to blows that day, although it’s unknown exactly what sparked the conflict.

Tacitus described this riot in Book XIV of his Annals:

About the same time a trifling beginning led to frightful bloodshed between the inhabitants of Nuceria and Pompeii, at a gladiatorial show exhibited by Livineius Regulus, who had been, as I have related, expelled from the Senate. With the unruly spirit of townsfolk, they began with abusive language of each other; then they took up stones and at last weapons, the advantage resting with the populace of Pompeii, where the show was being exhibited. And so there were brought to Rome a number of the people of Nuceria, with their bodies mutilated by wounds, and many lamented the deaths of children or of parents. The emperor entrusted the trial of the case to the Senate, and the Senate to the consuls, and then again the matter being referred back to the Senators, the inhabitants of Pompeii were forbidden to have any such public gathering for ten years, and all associations they had formed in defiance of the laws were dissolved. Livineius and the others who had excited the disturbance, were punished with exile.

Before now, the Tacitus passage, a fresco in the house of Actius Anicetus and three graffiti found on walls at Pompeii were the only explicit references to the amphitheater riot of 59. The funerary inscription adds a key piece of information about this event. Thanks to the deceased’s personal relationship with Nero, he was able to persuade him to allow the two duoviri exiled as punishment for the brawl to return to Pompeii. This is the only reference to the duoviri having been exiled as well as the only reference to the intercessionary role Maius played. It opens up the possibility that he was involved in the softening and lifting of the 10-year ban on public events at the amphitheater. It’s known that some combat spectacles like animal hunts took place during the first three years of the ban, and it was lifted entirely in 62 A.D. to celebrate the restoration of the amphitheater after an earthquake.

There is no name recorded in the inscription. It was probably in a larger font on a higher panel on the tomb facade which is now lost. Archaeologists are still excavating so it’s possible we’ll receive absolute confirmation of whether this is in fact the tomb of Gnaeus Alleius Nigidius Maius. Meanwhile, the res gestae inscription on the tomb, the first of its kind ever found in Pompeii, make it as close to a sure thing as we can get.

There is no name recorded in the inscription. It was probably in a larger font on a higher panel on the tomb facade which is now lost. Archaeologists are still excavating so it’s possible we’ll receive absolute confirmation of whether this is in fact the tomb of Gnaeus Alleius Nigidius Maius. Meanwhile, the res gestae inscription on the tomb, the first of its kind ever found in Pompeii, make it as close to a sure thing as we can get.

Another first of its kind discovery was made at this remarkable site. Just in front of the tomb are two cart ruts embedded in a layer of stone debris two meters (6.5 feet) thick. The debris is from the rockfall phase of the eruption, and tracks were left by people fleeing the city. These are the first archaeological remains of Pompeiians mid-flight ever found.

This clip from the Italian television show Petrolio captures the discovery of the funerary inscription: