In May of 2014, a 100-year-old architectural gem in Glasgow was devastated by fire. The Glasgow School of Art’s Mackintosh building, was designed by Charles Rennie Mackintosh, who had attended the Glasgow School of Art as a teenager, and built between 1897 and 1909. The Mack, as it is lovingly nicknamed, seamlessly blends multiple styles — modernism, Japonisme, Art Nouveau — and was enormously influential in its day. Today it is an icon of Glaswegian architecture, receiving more than 20,000 visitors a year, and its library was widely acknowledged as one of the greatest examples of Art Nouveau architecture in the world.

In May of 2014, a 100-year-old architectural gem in Glasgow was devastated by fire. The Glasgow School of Art’s Mackintosh building, was designed by Charles Rennie Mackintosh, who had attended the Glasgow School of Art as a teenager, and built between 1897 and 1909. The Mack, as it is lovingly nicknamed, seamlessly blends multiple styles — modernism, Japonisme, Art Nouveau — and was enormously influential in its day. Today it is an icon of Glaswegian architecture, receiving more than 20,000 visitors a year, and its library was widely acknowledged as one of the greatest examples of Art Nouveau architecture in the world.

Mackintosh’s undisputed masterpiece, The students were working on their final exams when one of them inadvertently set off a chain reaction that resulted in calamity. The spray foam she was using as part of her project was sucked into a projector’s cooling fan and set alight. The fire quickly spread throughout the west wing via the wooden flues that Mackintosh had installed to keep warm air circulating, reaching from the basement to the roof.

Mackintosh’s undisputed masterpiece, The students were working on their final exams when one of them inadvertently set off a chain reaction that resulted in calamity. The spray foam she was using as part of her project was sucked into a projector’s cooling fan and set alight. The fire quickly spread throughout the west wing via the wooden flues that Mackintosh had installed to keep warm air circulating, reaching from the basement to the roof.

Thanks to the prompt action of firefighters, the 200 students and staff in the building were evacuated and unharmed. By the time the fire was put out 12 hours later, three floors of the building had been consumed in the conflagration. The hard work and dedication of firefighters limited the damage so that 90% of

Thanks to the prompt action of firefighters, the 200 students and staff in the building were evacuated and unharmed. By the time the fire was put out 12 hours later, three floors of the building had been consumed in the conflagration. The hard work and dedication of firefighters limited the damage so that 90% of  The Mack remained intact, but the 10% that was destroyed unfortunately included two of the most significant parts of the building: the Japanese-inspired Studio 58 and the Mackintosh library, famed for its original built-in wood cabinets, furniture, windows and light fixtures. A long glazed corridor at the roof level known as the “hen run” also suffered heavy damage.

The Mack remained intact, but the 10% that was destroyed unfortunately included two of the most significant parts of the building: the Japanese-inspired Studio 58 and the Mackintosh library, famed for its original built-in wood cabinets, furniture, windows and light fixtures. A long glazed corridor at the roof level known as the “hen run” also suffered heavy damage.

Faced with such terrible devastation, the Glasgow School of Art had some hard decisions to make. So much was lost that there were serious questions about what could be recovered and at what cost. The final choice was to undertake the challenges of restoration preserving as many of the original elements as could be salvaged from the smoldering rubble. Volunteers flocked to help remove everything inside the building, from relatively unscathed sculptures and other artworks to charred and water-logged architectural features, decorations and furniture.

Faced with such terrible devastation, the Glasgow School of Art had some hard decisions to make. So much was lost that there were serious questions about what could be recovered and at what cost. The final choice was to undertake the challenges of restoration preserving as many of the original elements as could be salvaged from the smoldering rubble. Volunteers flocked to help remove everything inside the building, from relatively unscathed sculptures and other artworks to charred and water-logged architectural features, decorations and furniture.

What could not be salvaged and restored would be replaced with materials as close as to the originals as possible. The conservation team went above and beyond to rescue everything they could and recreate what they couldn’t. They were able to restore 28 of the Art Nouveau light fixtures from the library out of pieces salvaged from the fire, seven more were Frankensteined together from recovered parts and new parts, and 18 new replicas were made.

What could not be salvaged and restored would be replaced with materials as close as to the originals as possible. The conservation team went above and beyond to rescue everything they could and recreate what they couldn’t. They were able to restore 28 of the Art Nouveau light fixtures from the library out of pieces salvaged from the fire, seven more were Frankensteined together from recovered parts and new parts, and 18 new replicas were made.

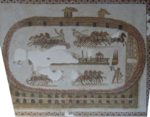

Studio 58 posed a whole other kind of challenge. It was built in Japanese-inspired style with a steep pitched roof held up by huge yellow pine beams. Because they performed an important structural function, the columns were made of massive, fine-grained timbers without weaknesses like large knot-holes and cracks. Replacing them was a dauntingly tall order.

Studio 58 posed a whole other kind of challenge. It was built in Japanese-inspired style with a steep pitched roof held up by huge yellow pine beams. Because they performed an important structural function, the columns were made of massive, fine-grained timbers without weaknesses like large knot-holes and cracks. Replacing them was a dauntingly tall order.

That’s when the historic cotton mill complex in Lowell, Massachusetts, the epicenter of the industrial revolution in the United States, came to the rescue. One of the last buildings added to the complex, the 1904 Picker Building, is in the process of being converted into affordable apartments. Last year a section of it had to be demolished, but every part of it that could be salvaged was reclaimed before the demolition. Among the salvaged elements were very high-quality, old growth southern yellow pine timbers used to frame the structure. They were recovered and stored by Longleaf Lumber, experts the salvage of historic woods.

That’s when the historic cotton mill complex in Lowell, Massachusetts, the epicenter of the industrial revolution in the United States, came to the rescue. One of the last buildings added to the complex, the 1904 Picker Building, is in the process of being converted into affordable apartments. Last year a section of it had to be demolished, but every part of it that could be salvaged was reclaimed before the demolition. Among the salvaged elements were very high-quality, old growth southern yellow pine timbers used to frame the structure. They were recovered and stored by Longleaf Lumber, experts the salvage of historic woods.

Liz Davidson, Senior Project Manager for the Mackintosh Restoration:

“The original wooden uprights had been made out of American yellow pine which we knew had come from Massachusetts. So when our contractor, Kier Construction, began the search for replacement timber they immediately looked into possible sources in the area where the original timber had come from at the turn of the 20th century.”

“We were delighted to discover that not only did Long Leaflumber have the quality yellow pine in the size that we needed, but that the wood had come from a building which had been constructed at the same time as the Mack,” she adds.

“Longleaf Lumber are truly excited and humbled to be part of such a tremendous restoration project,” a spokesperson said. “It is fitting that these beams, cut from the grand longleaf pine forests and originally milled for a factory in the birthplace of the American Industrial Revolution, have been reclaimed and repurposed in a restoration effort that pays homage to an architectural master who was influenced both by nature and the industrial changes of his time.”

Eight 13-1/2 inch x 15-1/2 inch x 23 foot beams were loaded into a shipping container in late 2016 for the trip across the Atlantic and arrived in Scotland at the beginning of this year. After testing and shaping the wood was ready for the final part of its journey from Cotton Mill to Artists studio.

Four massive replacement uprights were finally craned into the Mackintosh Building and manoeuvred into place in a delicate and complex operation. This landmark day cemented the relationship between Glasgow and Massachusetts which had begun over a century ago at the time when both the Picker Building and the Mackintosh Building were constructed.

The restoration of Mackintosh Building is a labour of love, but with more than 30 specialized subcontractors from lead glaziers to horse-hair plasterers involved, it’s far from cheap with an estimated total cost of £35 million ($43 million). A great deal of money has been raised already, but there is still a long way to go. If you’d like to donate to the fund, click here if you’re in the UK, or here if you’re in the US. If all goes according to schedule, the restoration will be completed by February 2019.