Archaeologists have discovered an ancient pre-Hispanic, pre-Inca Wari temple at the archaeological site of Espíritu Pampa in the jungles of Peru’s La Convención province. The team first found the walls shaped like a capital D, a characteristic design for Wari culture temples. A second, smaller D-shaped structure was found in the middle of the big D. Archaeologists believe this was likely an astronomical observatory, a key element of Wari worship and important section of the full temple. It may also have been used to perform religious rituals.

Archaeologists have discovered an ancient pre-Hispanic, pre-Inca Wari temple at the archaeological site of Espíritu Pampa in the jungles of Peru’s La Convención province. The team first found the walls shaped like a capital D, a characteristic design for Wari culture temples. A second, smaller D-shaped structure was found in the middle of the big D. Archaeologists believe this was likely an astronomical observatory, a key element of Wari worship and important section of the full temple. It may also have been used to perform religious rituals.

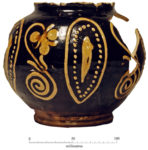

Also inside the larger temple walls, the archaeological team discovered two burial pits built with small slabs of stone. The first of these was found to contain tooth fragments from an animal. The second burial contained to large Wari ceramic vessels, a silver pectoral band and one silver crown or headdress. One of the pots was particularly striking (and very much typical of Wari craftsmanship), a stylized representation of a crowned individual with large and prominent eyes, nose and mouth. The crown is painted on and is first archaeological evidence that Espíritu Pampa was home to a ruling elite during the heyday of Wari power.

Also inside the larger temple walls, the archaeological team discovered two burial pits built with small slabs of stone. The first of these was found to contain tooth fragments from an animal. The second burial contained to large Wari ceramic vessels, a silver pectoral band and one silver crown or headdress. One of the pots was particularly striking (and very much typical of Wari craftsmanship), a stylized representation of a crowned individual with large and prominent eyes, nose and mouth. The crown is painted on and is first archaeological evidence that Espíritu Pampa was home to a ruling elite during the heyday of Wari power.

When that day no longer made hey, the last hurrah of Inca independence filled the void, and there’s evidence of that too in the physical structure of the temple. On the long edge of the D-shaped enclosure, there are architectural remains of square and rectangular design. This is Inca work. The interior confirmed this identification when archaeologists unearthed tupus, silver needles and ceramic bottles and assorted vessels used for ceremonial purposes.

When that day no longer made hey, the last hurrah of Inca independence filled the void, and there’s evidence of that too in the physical structure of the temple. On the long edge of the D-shaped enclosure, there are architectural remains of square and rectangular design. This is Inca work. The interior confirmed this identification when archaeologists unearthed tupus, silver needles and ceramic bottles and assorted vessels used for ceremonial purposes.

This second, later habitation by the Inca had a brief but significant heyday in the 16th century. As the Spanish conquest proceeded at a precipitous rate, Manco Inca Yupanqui defied the Spanish rulers who had installed him to be their puppet king. When Francisco Pizarro left his two bratty younger brothers behind in Cusco as regents (ie, the real rulers), they were so vicious and disrespectful that Manco Inca rebelled. He fought them in open combat, besieging Cusco for 10 months. He was successful at first, but eventually left the highlands to the Spanish and moved to the remote jungle were he founded the independent Neo-Inca State in his new capital of Vilcabamba in 1539.

This second, later habitation by the Inca had a brief but significant heyday in the 16th century. As the Spanish conquest proceeded at a precipitous rate, Manco Inca Yupanqui defied the Spanish rulers who had installed him to be their puppet king. When Francisco Pizarro left his two bratty younger brothers behind in Cusco as regents (ie, the real rulers), they were so vicious and disrespectful that Manco Inca rebelled. He fought them in open combat, besieging Cusco for 10 months. He was successful at first, but eventually left the highlands to the Spanish and moved to the remote jungle were he founded the independent Neo-Inca State in his new capital of Vilcabamba in 1539.

Not quite so new, as it happens. Vilcabamba and Espíritu Pampa are the same city. Manco wisely selected a spot that already had surviving ancient architecture (the Wari Empire lasted from around 600 A.D. to 1100 A.D.) to piggyback off on — a major advantage in the jungle — and then proceeded to do just that. The distant location did not keep the fledgling independent state safe. There was near-constant fighting in the hills, not just between Inca and Spanish, but between Spanish factions, the first civil war to break out between the conquistadores in Peru. It was that subconflict that ultimately led to Manco’s death. He was killed by members of the anti-Pizarro faction who were hiding out in Vilcabamba under Manco’s generous protection. In exchange for his support, they murdered him in 1544. Manco’s men returned the favor.

Not quite so new, as it happens. Vilcabamba and Espíritu Pampa are the same city. Manco wisely selected a spot that already had surviving ancient architecture (the Wari Empire lasted from around 600 A.D. to 1100 A.D.) to piggyback off on — a major advantage in the jungle — and then proceeded to do just that. The distant location did not keep the fledgling independent state safe. There was near-constant fighting in the hills, not just between Inca and Spanish, but between Spanish factions, the first civil war to break out between the conquistadores in Peru. It was that subconflict that ultimately led to Manco’s death. He was killed by members of the anti-Pizarro faction who were hiding out in Vilcabamba under Manco’s generous protection. In exchange for his support, they murdered him in 1544. Manco’s men returned the favor.

The artifacts have been recovered from the dig and are slated to get a thorough cleaning, conservation and examination by experts at the Physical Chemistry Unit of the Decentralized Directorate of Culture of Cusco.