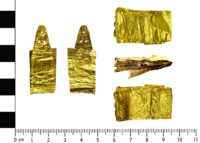

Some of Britain’s oldest gold has been declared treasure two years after it was found in a box of assorted watch parts bought by John Workman at the Berinsfield Car Boot sale in south Oxfordshire. The Oxford Coroner’s Court ruled on April 17th that the folded gold strip dating to the Early Bronze Age qualifies as treasure on the grounds of its prehistoric age and its high percentage of precious metal content.

Some of Britain’s oldest gold has been declared treasure two years after it was found in a box of assorted watch parts bought by John Workman at the Berinsfield Car Boot sale in south Oxfordshire. The Oxford Coroner’s Court ruled on April 17th that the folded gold strip dating to the Early Bronze Age qualifies as treasure on the grounds of its prehistoric age and its high percentage of precious metal content.

The number of objects of this age and type discovered in Britain can literally be counted on the fingers of one hand. They date to around 2400-200 B.C., which make them the earliest gold artifacts in Britain. The strip is now in two pieces but that happened after it was folded and lost. Even put together the two pieces do not make up the complete original and because there is no find site or any way of locating it, the odds of finding missing fragments are infinitesimally small.

There are punched dots along the edge of the tapered end and three circles pierced through another terminal in a triangular shape. These could be decorative features or evidence that the gold was once mounted to something — a scabbard, jewelry, clothing. A similar strip found near Winchester in 2000 and now in the collection of the British Museum is also perforated at the terminal in a triangular shape.

Mr Workman spotted the unusual piece and showed it to friends who had interest in metal detecting and was encouraged to get in touch with the British Museum.

[Oxfordshire Finds liaison officer Anni] Byard described the piece as ‘exceptionally rare’ and said ‘very rare doesn’t seem to do it justice’.

She added: “As soon as I heard about it I knew it was Bronze Age and realised it was pretty unusual and quite rare.

“Because they are so rare we don’t know what they would have been used for, it could have been on the side of a sword or could have been worn around the neck as jewellery. We just don’t know.”

Now that it has been ruled official treasure, the gold strip is property of the crown and will be assessed for fair market value. A local museum will be given first dibs at acquiring it for the assessed value, the award to go to the finder. The Oxfordshire Museum is keen to secure the piece for the county. The monetary value won’t be prohibitive. The Winchester strip was valued at £2,000, and while this piece is a little larger and gold has increased in value since then, it should still be well within reach of the Oxfordshire Museum. Its historic value, of course, is inestimable.