The 10th century Viking raid that destroyed the powerful Pictish hill fort of Burghead in Moray, northeastern Scotland, has the unintended consequence of preserving archaeological material that would otherwise have decayed into nothingness by now. The fire that razed the fort and ended more than three centuries of Pictish life at the largest and oldest fort in what is now Scotland charred organic remains and kept them from rotting.

Until recently, there hasn’t been a great deal of archaeological exploration of the fort site because it was presumed to have been largely obliterated. To paraphrase a famous pasquinade, Quod non fecerunt Vikingi fecerunt Scoti. When the modern town of Burghead was built between 1805 and 1809, more than half of the hill fort’s remains were destroyed. The elements and coastal erosion have been chipping away at everything else at an alarming rate.

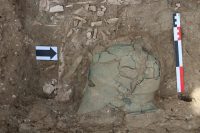

In 2015, a team of archaeologists from the University of Aberdeen began excavating inside the defensive walls and several significant discoveries were unearthed, including a Pictish longhouse and a late 9th century Anglo-Saxon coin of Alfred the Great. This April the team for the first time turned their spades and brushes on the lower citadel and the sea-facing ramparts of the upper citadel. Much to their surprise, they found wood timbers in excellent condition in both locations. The timbers in the lower citadel were part of a massive defensive wall that would have been 20 feet high in its heyday.

In 2015, a team of archaeologists from the University of Aberdeen began excavating inside the defensive walls and several significant discoveries were unearthed, including a Pictish longhouse and a late 9th century Anglo-Saxon coin of Alfred the Great. This April the team for the first time turned their spades and brushes on the lower citadel and the sea-facing ramparts of the upper citadel. Much to their surprise, they found wood timbers in excellent condition in both locations. The timbers in the lower citadel were part of a massive defensive wall that would have been 20 feet high in its heyday.

[University of Aberdeen head of archaeology] Dr Noble explains: “We are fortunate to have the descriptions of the site written by Hugh Young in 1893. He describes a lattice work of oak timbers which would have acted as an enormous defensive barrier and must have been a hugely complex feat of engineering in the early medieval period.

“In the years that have passed since he made his observations, the Burghead Fort has unfortunately been subject to significant coastal erosion and the harsh North Sea environment.

“But when we started digging, we discovered that while the destruction of the fort in the 10th century may not have been good news for the Picts, the fact that so much of it was set alight is a real bonus for archaeologists.

“We have discovered that the complex layer of oak planks set in the wall was burned in situ and that the resulting charring has actually preserved it in amazing detail when ordinarily it would have rotten away to nothing by now.”

On the other side of the size scale, Pictish jewelry has been discovered at the fort, among them a bronze ring, a mace-headed pin and a hair or dress pin with a bramble design on the head. They’ve also had the good fortune of finding the fine archaeological resource that is old garbage. The team has unearthed several midden layers from the Pictish era which will shed new light on the daily lives of a people who left no written records. Here too remains have been unusually well preserved.

On the other side of the size scale, Pictish jewelry has been discovered at the fort, among them a bronze ring, a mace-headed pin and a hair or dress pin with a bramble design on the head. They’ve also had the good fortune of finding the fine archaeological resource that is old garbage. The team has unearthed several midden layers from the Pictish era which will shed new light on the daily lives of a people who left no written records. Here too remains have been unusually well preserved.

“What’s exciting is the level of preservation here. We’ve found animal bone which rarely survives in mainland Scotland because of the acidic soil. We are already getting really nice information about what people ate within the fort and we hope to extract a level of information we’ve not had for Pictish sites before.”

Excavations are over for the season. The University of Aberdeen team plans to return next year to work the coastal area which is under dire threat from erosion. The timber wall is less than five feet from the erosion line, so the next excavation will be under the pressure of a salvage mission.

Excavations are over for the season. The University of Aberdeen team plans to return next year to work the coastal area which is under dire threat from erosion. The timber wall is less than five feet from the erosion line, so the next excavation will be under the pressure of a salvage mission.