Oxford medieval history professor George Garnett has counted 93 penises, human and equine, on the Bayeux Tapestry. The vast majority of them, 88 to be precise, are horse penises from the central panel where all the historic action takes place. The five human penises (plus one possible one) are only found in the top and bottom borders.

Oxford medieval history professor George Garnett has counted 93 penises, human and equine, on the Bayeux Tapestry. The vast majority of them, 88 to be precise, are horse penises from the central panel where all the historic action takes place. The five human penises (plus one possible one) are only found in the top and bottom borders.

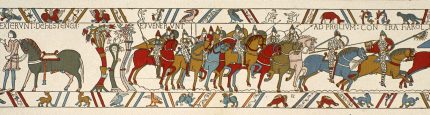

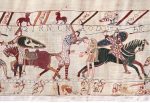

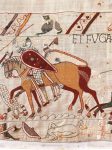

It makes sense that the equine genitalia would be so distinct and prolific. The embroiderers who created the tapestry (a misnomer, by the way, because it’s wool thread embroidered on linen panels, not a woven textile) were far more precise in their depiction of horses than of people. There are about 200 horses on the Bayeux Tapestry, embroidered with realistic color, tack, wooden saddles and stirrups. Some are destriers, some palfreys, some packhorses, all of them clearly distinguishable. Even the gaits can be identified in battle scenes.

It makes sense that the equine genitalia would be so distinct and prolific. The embroiderers who created the tapestry (a misnomer, by the way, because it’s wool thread embroidered on linen panels, not a woven textile) were far more precise in their depiction of horses than of people. There are about 200 horses on the Bayeux Tapestry, embroidered with realistic color, tack, wooden saddles and stirrups. Some are destriers, some palfreys, some packhorses, all of them clearly distinguishable. Even the gaits can be identified in battle scenes.

The penises of the horses convey rather obvious meaning about their riders. The bigger the phallus, the greater the power.

The penises depicted on certain stallions might be thought to demonstrate no more than the designer’s scrupulous anatomical accuracy. But it cannot be simply a coincidence that Earl Harold is first shown mounted on an exceptionally well-endowed steed. And the largest equine penis by far is that protruding from the horse presented by a groom to a figure who must be Duke William, just prior to the battle of Hastings.

This, the viewer is meant to infer, was the charger on which the duke fought. The clear implications are that the virility of the two leading protagonists is reflected in that of their respective mounts, and that William was in this respect much the more impressive of the two, as the denouement of what survives of the tapestry showed to be the case. Odo of Bayeux, the duke’s half-brother, plays a very important role in the action, but although he is depicted in the thick of the fray, cockily rallying the Norman forces at a critical juncture, the genitalia of his very large horse are modest indeed by comparison.

That might be thought only appropriate in a senior man of the cloth, sworn to celibacy, but it is also true of all other mounted participants in the battle, who appear to be laymen. Duke William had to be the outstanding individual in every respect, including his horse’s penis

“Cockily rallying,” eh? I see what you did there, Professor Garnett. It’s worth noting that Odo, Bishop of Bayeux, is the person who commissioned the tapestry so his horse’s modest endowment compared to his half-brother’s steed’s impressive one could have been a form of genuflection or currying favor.

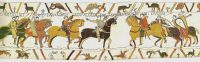

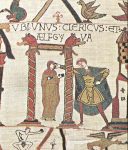

The exposed human genitals are less obvious and therefore more intriguing in their meaning. There’s a naked man with an erect phallus reaching out towards a nude woman covering her face and crotch with her hands. Emory University professor emeritus of medieval history Stephen White has posited that this could be a scene from Phaedrus’s Latin versions of Aesop’s fables, namely a tale of a father who raped his daughter. It’s at the beginning of the tapestry under the scene where Earl Harold (Edward the Confessor is still alive at this point) is taken prisoner in France and taken to Duke William. The bottom frieze designs from this scene forward feature several animals stories from the fables — the Fox and the Crow, the Wolf and the Lamb, the Bitch and her Puppies, etc. — so it’s reasonable to think the dramatic human postures were inspired the tales as well.

The exposed human genitals are less obvious and therefore more intriguing in their meaning. There’s a naked man with an erect phallus reaching out towards a nude woman covering her face and crotch with her hands. Emory University professor emeritus of medieval history Stephen White has posited that this could be a scene from Phaedrus’s Latin versions of Aesop’s fables, namely a tale of a father who raped his daughter. It’s at the beginning of the tapestry under the scene where Earl Harold (Edward the Confessor is still alive at this point) is taken prisoner in France and taken to Duke William. The bottom frieze designs from this scene forward feature several animals stories from the fables — the Fox and the Crow, the Wolf and the Lamb, the Bitch and her Puppies, etc. — so it’s reasonable to think the dramatic human postures were inspired the tales as well.

In the top frieze while the main panel is depicting the Normans ride to battle there are two sets of naked figures. One is a man whose penis is obscured by a large axe he’s holding, but his testicles are clearly visible behind him. He’s holding out something unidentifiable to a nude woman. A few inches to the right of them are a naked man and a woman. The first could refer to a fable in which a widow has a sexual relationship with the man guarding the cemetery where her husband’s body is buried. To cover up his negligence after a body is stolen when they’re having sex, the widow gives him her husband’s body to substitute for the stolen one. The second couple might be from a story in which a prostitute claims to be in love with her client and he doesn’t believe her.

The last two naked men are individuals in the bottom border. One is bent over pulling an axe out of a container or off a cloth. The other is squatting and just letting it all hang out. The first could be referring to the fable in which an axe-maker persuades trees to let him use their wood to make a handle and then chops them down once he’s made his axe. The second has no Aesopian explanation.

The last two naked men are individuals in the bottom border. One is bent over pulling an axe out of a container or off a cloth. The other is squatting and just letting it all hang out. The first could be referring to the fable in which an axe-maker persuades trees to let him use their wood to make a handle and then chops them down once he’s made his axe. The second has no Aesopian explanation.

(The sixth possible penis belongs to a dead soldier, stripped of his mail and clothes after falling on the battlefield of Hastings. It’s sort of a single curved line in the crotchal region that doesn’t connect to anything else, so while it looks like a side view of a flopped over penis, it’s difficult to confirm or deny. Please appreciate that I said “difficult,” not “hard.” Because I’m classy.)

(The sixth possible penis belongs to a dead soldier, stripped of his mail and clothes after falling on the battlefield of Hastings. It’s sort of a single curved line in the crotchal region that doesn’t connect to anything else, so while it looks like a side view of a flopped over penis, it’s difficult to confirm or deny. Please appreciate that I said “difficult,” not “hard.” Because I’m classy.)

As with all of Aesop’s fables, they come with moral lessons, ones that educated viewers would have recognized. The ones depicted in the borders of the tapestry revolve around betrayal, deceit, untrustworthiness, and were probably meant to be visual allegorical comments on the action in the main panel. With penises.