An ancient papyrus in the collection of the University of Basel has been deciphered 500 years after it made its way to Switzerland. Basel was the first university in German-speaking Switzerland one of the first German-language universities to acquire a papyrus collection. It was 1900 and large groups of papyri had only recently begun to be found preserved in the arid heat of the Egyptian desert. The 65 papyrus fragments bought by the university were written in five languages (Greek, Latin, Coptic Egyptian and hieratic) in the Late Ptolemaic, Roman and Coptic eras. They consist of everyday documents including contracts, loans, tax receipts, letters and petitions.

This was probably a disappointment to scholars exploring the nascent field of papyrology when the collection was acquired because the impetus that drove the papyrus fever of the late 19th century was the prospect of new sources for momentous historical events like the dawn of Christianity and finding the lost books of classical antiquity. A contract to transport a confiscated camel was not exactly the dream document. The collection was stashed away and forgotten until the papyri were rediscovered in two manuscript drawers in the University of Basel’s library in 2015.

Because of their long lapse into obscurity, the papyrus texts were all but unknown in the scholarly community and had never been properly recorded, researched and published. Over the past three years, an interdisciplinary team has worked in the University of Basel’s Digital Humanities Lab to analyze the papyri with imaging technology as the texts are transcribed, translated, annotated and digitized.

Part of the Basel collection are two papyri that were not purchased in 1900. They weren’t purchased in 1800. Or 1700. They were acquired in the second half of the 16th century by lawyer and avid collector Basilius Amerbach for his spectacular cabinet of curiosities. The Amerbach collection was started by his father Bonifacius. The son inherited it in 1562 and he was even more extravagant than his father in both reach and grasp. How he got his hands on papyri is not clear, but researchers think he probably bought them in Italy 300 years before the first major papyrus finds in Egypt were snapped up by the antiquities magpies in Europe. They were so rare at that time that many Western scholars saw their first papyrus in the Amerbach collection.

Part of the Basel collection are two papyri that were not purchased in 1900. They weren’t purchased in 1800. Or 1700. They were acquired in the second half of the 16th century by lawyer and avid collector Basilius Amerbach for his spectacular cabinet of curiosities. The Amerbach collection was started by his father Bonifacius. The son inherited it in 1562 and he was even more extravagant than his father in both reach and grasp. How he got his hands on papyri is not clear, but researchers think he probably bought them in Italy 300 years before the first major papyrus finds in Egypt were snapped up by the antiquities magpies in Europe. They were so rare at that time that many Western scholars saw their first papyrus in the Amerbach collection.

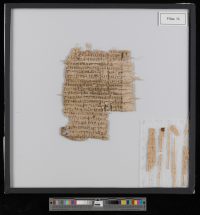

After Basilius’ death, the papyri went to the University of Basel where he had been a professor for many years. One of the two has been confounding experts ever since. It has mirror writing on both sides that nobody has been able to decipher. As part of the university’s papyrus recording and digitization project, the mystery papyrus was photographed with ultraviolet and infrared light. This revealed that the papyrus was not technically A papyrus, but rather a multi-layer composite made from several papyrus fragments that had been glued together, likely by a bookbinder during the Middle Ages, to use the thickened linen piece as a cover.

The Basel team didn’t have the chance to use a particle accelerator to read through the layers, so they turned to good ol’ fashioned human expertise and patience. They called in a specialist in papyrus restoration and he painstakingly separated the sheets with tools like a scalpel and Q-Tips. Once the sheets were singletons again, the Greek could be read for the first time in centuries.

“This is a sensational discovery,” says Sabine Huebner, Professor of Ancient History at the University of Basel. “The majority of papyri are documents such as letters, contracts and receipts. This is a literary text, however, and they are vastly more valuable.”

What’s more, it contains a previously unknown text from antiquity. “We can now say that it’s a medical text from late antiquity that describes the phenomenon of ‘hysterical apnea’,” says Huebner. “We therefore assume that it is either a text from the Roman physician Galen, or an unknown commentary on his work.” After Hippocrates, Galen is regarded as the most important physician of antiquity.

Last year, the full Basel papyrus collection got its long-awaited moment in the sun when the project team presented their research in the form an exhibition at the library. The final results of the project’s work will be published in early 2019.

With the end of the editing project, the research on the Basel papyri will enter into a new phase. Huebner hopes to provide additional impetus to papyrus research, particularly through sharing the digitalized collection with international databases. As papyri frequently only survive in fragments or pieces, exchanges with other papyrus collections are essential. “The papyri are all part of a larger context. People mentioned in a Basel papyrus text may appear again in other papyri, housed for example in Strasbourg, London, Berlin or other locations. It is digital opportunities that enable us to put these mosaic pieces together again to form a larger picture.”