Researchers at the British Museum solved a mystery both ancient and modern when they discovered the origin site of eight artifacts looted from Iraq after the fall of Saddam Hussein. Thanks to their efforts, the objects are now on their way back to Iraq.

Researchers at the British Museum solved a mystery both ancient and modern when they discovered the origin site of eight artifacts looted from Iraq after the fall of Saddam Hussein. Thanks to their efforts, the objects are now on their way back to Iraq.

The orphaned artifacts were in custody of the British Museum after having been seized in a police raid on a London antiquities dealer in  May 2003. The dealer had no proof of ownership — I guess he hadn’t gotten around to forging a “Swiss private collection” document yet — or any other documentation about the artifacts, so they were confiscated by the authorities and were in storage for almost 15 years.

May 2003. The dealer had no proof of ownership — I guess he hadn’t gotten around to forging a “Swiss private collection” document yet — or any other documentation about the artifacts, so they were confiscated by the authorities and were in storage for almost 15 years.

The cold case was heated up when the Metropolitan Police reformed its art and antiquities squad. The squad gave the objects to the British Museum this year in the hope that its experts might be able to figure out where the pieces came from so they could be repatriated. As it turned out, the British Museum was uniquely well-positioned to uncover the truth about these objects.

The cold case was heated up when the Metropolitan Police reformed its art and antiquities squad. The squad gave the objects to the British Museum this year in the hope that its experts might be able to figure out where the pieces came from so they could be repatriated. As it turned out, the British Museum was uniquely well-positioned to uncover the truth about these objects.

The eight artifacts consist of three fired clay cones with Sumerian cuneiform inscriptions, a fragment of a white gypsum mace-head inscribed in Sumerian, a polished river pebble with a cuneiform inscription in Sumerian, one red marble and one white marble stamp-seal amulet from the Jemdet Nasr period (ca. 3000 B.C.) in the form of a reclining sheep and one banded white chalcedony seal of a reclining sphinx from the Achaemenid period.

The eight artifacts consist of three fired clay cones with Sumerian cuneiform inscriptions, a fragment of a white gypsum mace-head inscribed in Sumerian, a polished river pebble with a cuneiform inscription in Sumerian, one red marble and one white marble stamp-seal amulet from the Jemdet Nasr period (ca. 3000 B.C.) in the form of a reclining sheep and one banded white chalcedony seal of a reclining sphinx from the Achaemenid period.

It was the three cones that gave the British Museum the information they needed to pinpoint the origin site. The all bore the identical Sumerian inscription, one that is also know from other inscribed ancient artifacts. It reads: “For Ningirsu, Enlil’s mighty warrior, Gudea, ruler of Lagash, made things function as they should (and) he built and restored for him his Eninnu, the White Thunderbird.” This inscription identified the cones as coming from the archaeological city of Girsu (modern-day Tello) in southern Iraq where the Eninnu temple once stood. The temple was sacred Eninnu’s patron god Ningirsu.

It was the three cones that gave the British Museum the information they needed to pinpoint the origin site. The all bore the identical Sumerian inscription, one that is also know from other inscribed ancient artifacts. It reads: “For Ningirsu, Enlil’s mighty warrior, Gudea, ruler of Lagash, made things function as they should (and) he built and restored for him his Eninnu, the White Thunderbird.” This inscription identified the cones as coming from the archaeological city of Girsu (modern-day Tello) in southern Iraq where the Eninnu temple once stood. The temple was sacred Eninnu’s patron god Ningirsu.

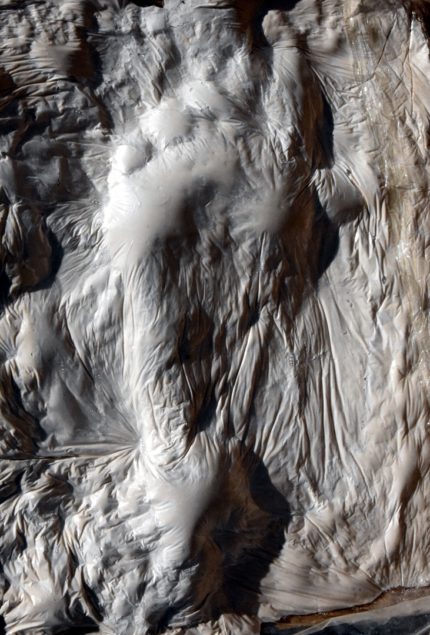

The great temple complex is in the Tell A area of Tello where ongoing excavations have found artifacts and remains elucidating the plan, size and design of the temple. Archaeologists from the British Museum have been excavating Tell A since 2016 as part of the Iraq Emergency Heritage Management Training Scheme, a program set up in response to the IS destruction of cultural patrimony that trains staff from the Iraq State Board of Antiquities and Heritage in the latest techniques of rescue archaeology. The initial survey of Tello in 2015 and 2016 found dozens of looter pits. They were shallow and appear to have been targeted, small-scale efforts probably done at night by a few individuals rather than the massive looting operations that ran roughshod over Iraq’s ancient sites in 2003.

The great temple complex is in the Tell A area of Tello where ongoing excavations have found artifacts and remains elucidating the plan, size and design of the temple. Archaeologists from the British Museum have been excavating Tell A since 2016 as part of the Iraq Emergency Heritage Management Training Scheme, a program set up in response to the IS destruction of cultural patrimony that trains staff from the Iraq State Board of Antiquities and Heritage in the latest techniques of rescue archaeology. The initial survey of Tello in 2015 and 2016 found dozens of looter pits. They were shallow and appear to have been targeted, small-scale efforts probably done at night by a few individuals rather than the massive looting operations that ran roughshod over Iraq’s ancient sites in 2003.

The British Museum team at Tello found broken cones identical to those seized in London. Their shape was an imitation of tent pegs and they were originally placed in holes in the temple wall, offerings to the Sumerian Thunderbird, the lion-headed god who roared thunder and flashed lightning bolts from his body. That’s how the researchers were able to discover not just the site where the objects had been looted from, but the actual wall they had been inserted in originally.

The British Museum team at Tello found broken cones identical to those seized in London. Their shape was an imitation of tent pegs and they were originally placed in holes in the temple wall, offerings to the Sumerian Thunderbird, the lion-headed god who roared thunder and flashed lightning bolts from his body. That’s how the researchers were able to discover not just the site where the objects had been looted from, but the actual wall they had been inserted in originally.

On Friday, August 10th, the artifacts were officially returned to the Iraqi ambassador Salih Husain Ali in a ceremony at the British Museum.

Iraqi ambassador Salih Husain Ali … said the protection of antiquities was an international responsibility and praised the British Museum and its staff “for their exceptional efforts in the process of identifying and returning looted antiquities to Iraq. Such collaboration between Iraq and the United Kingdom is vital for the preservation of Iraqi heritage.”

Iraqi ambassador Salih Husain Ali … said the protection of antiquities was an international responsibility and praised the British Museum and its staff “for their exceptional efforts in the process of identifying and returning looted antiquities to Iraq. Such collaboration between Iraq and the United Kingdom is vital for the preservation of Iraqi heritage.”

St John Simpson, the assistant keeper at the Middle East department of the museum, said: “Uniquely we could trace them not just to the site but to within inches of where they were stolen from. This is a very happy outcome, nothing like this has happened for a very, very long time if ever.”

They will be returned to the national museum in Baghdad and reunited with many objects from the recent excavations, and may eventually be loaned to a museum near the site.

Archaeologists have discovered a human footprint left 3,000 years ago at the ancient fortress of Van Castle in southeastern Turkey. The print of a right foot is just over 10 inches long, the equivalent of a modern-day men’s size 9 (US) or 42 (European), and belonged to a young man of the Iron Age Urartu civilization which dominated this region of Anatolia from the 9th through the 7th century B.C. This is the first time since excavations began in 2015 that a print directly linked to an Urartu individual has been found at the site.

Archaeologists have discovered a human footprint left 3,000 years ago at the ancient fortress of Van Castle in southeastern Turkey. The print of a right foot is just over 10 inches long, the equivalent of a modern-day men’s size 9 (US) or 42 (European), and belonged to a young man of the Iron Age Urartu civilization which dominated this region of Anatolia from the 9th through the 7th century B.C. This is the first time since excavations began in 2015 that a print directly linked to an Urartu individual has been found at the site. Van Castle was built in the 8th and 7th centuries B.C., the heyday of the Urartian kingdom, also known as the Kingdom of Van. The clifftop fortress overlooked the capital city of Tushpa but it was not a defensive installation. Rather it was an instrument of regional control, one of multiple such citadels built in Urartu territory. Van is the largest of them all.

Van Castle was built in the 8th and 7th centuries B.C., the heyday of the Urartian kingdom, also known as the Kingdom of Van. The clifftop fortress overlooked the capital city of Tushpa but it was not a defensive installation. Rather it was an instrument of regional control, one of multiple such citadels built in Urartu territory. Van is the largest of them all. The citadel was constructed of a basalt stone foundation with mud brick walls, and the houses within its walls and in Tushpa were also made of mud brick. Archaeologists believe the footprint was left in wet mudbrick during the construction of one of those homes, likely by a male between 13 and 15 years of age.

The citadel was constructed of a basalt stone foundation with mud brick walls, and the houses within its walls and in Tushpa were also made of mud brick. Archaeologists believe the footprint was left in wet mudbrick during the construction of one of those homes, likely by a male between 13 and 15 years of age.