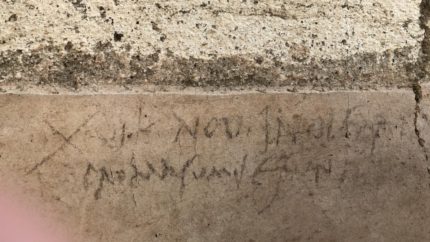

A charcoal date scribbled on the wall of a villa in Pompeii that was undergoing renovations when it was buried by the eruption of Vesuvius in 79 A.D. is the most precise contemporary evidence yet that the traditional date of the destruction of Pompeii, August 24th, is off by months. The note is dated the 16th day before the Kalends of November (November 1st), which would have been October 17th. There is no year, but the inscription wasn’t meant to be permanent. It was written in charcoal on a white wall that was probably going to be frescoed over as part of a renovation of the home and even if it hadn’t been painted, the charcoal would have quickly faded. That’s why archaeologists are so sure it was left in 79 A.D.

A charcoal date scribbled on the wall of a villa in Pompeii that was undergoing renovations when it was buried by the eruption of Vesuvius in 79 A.D. is the most precise contemporary evidence yet that the traditional date of the destruction of Pompeii, August 24th, is off by months. The note is dated the 16th day before the Kalends of November (November 1st), which would have been October 17th. There is no year, but the inscription wasn’t meant to be permanent. It was written in charcoal on a white wall that was probably going to be frescoed over as part of a renovation of the home and even if it hadn’t been painted, the charcoal would have quickly faded. That’s why archaeologists are so sure it was left in 79 A.D.

The source of the August date for the eruption is Pliny the Younger. It’s found in a letter written to his friend the historian Tacitus three decades after he witnessed Vesuvius’ fury destroy Pompeii, but the date has been questioned since the early days of Pompeiian archaeology. The discovery of organic remains of autumnal produce like pomegranates, chestnuts, grapes and of heating braziers in homes suggested the city had not been destroyed in the sweltering heat of a southern Italian August. One silver coin also provided strong evidence of a fall date. Minted by the Emperor Titus in 79 A.D., the coin is inscribed with a list of the emperor’s titles one of which notes he was acclaimed imperator 15 times. Titus’ 15th acclamation as emperor took place on September 8th.

So if the eruption took place in October, how to explain Pliny’s letter to Tacitus describing it as having happened in August? He barely escaped a cataclysm that destroyed multiple cities and claimed his uncle’s life. It’s not the sort of thing you’re likely to get so wrong, even 30 years after the event. The answer is transcription errors. Pliny’s original correspondence has not survived, obviously. The text has come down to us in various states of completion from copyists and, like a game of telephone, mistakes get transmitted and even amplified over the centuries. It’s easy to see how scribes might have confused September (the ninth month of the Julian calendar) with November (the ninth month in the ancient Roman 10-month calendar as indicated by the prefix “nov”).

Ancient sources are never as cut and dried as we might wish. There are inconsistencies with the archaeological record and even among the extant manuscripts. The August date comes from the most complete surviving copy of the letter which refers to the “nonum kal. septembres” (nine days before kalends of Septembe), not from all of them. Other copies of Pliny’s letters, including one now in the Girolamini Library in Naples, refer to the kalends of November, three days before the kalends of November and nine days before the kalends (month missing but was probably also November).