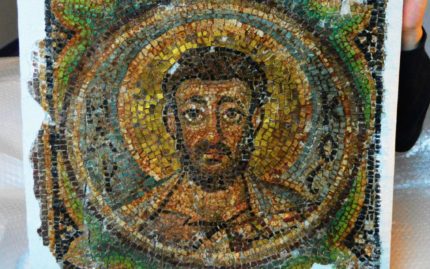

A 6th century mosaic of St. Mark torn from the walls of Panagia Kanakaria church in northern Cyprus in the wake of the 1974 Turkish invasion has been repatriated. The monastery church, originally built in the 5th century, was renown for its early Byzantine mosaics depicting Jesus, Mary and the apostles. They were extremely rare, stylistically unique and some of the most important early Christian art in the world by virtue of having survived the Iconoclastic orgy of destruction during the 8th and 9th centuries.

In the late 1970s, they were plundered and sold in pieces to unscrupulous dealers who sold them all over the world to equally unscrupulous buyers. With a great deal of work by heritage organizations, police and committed individuals, almost all of the mosaics have been found in the decades since the brutalization of Panagia Kanakaria. Most recently, the medallion of the apostle St. Andrew was repatriated this April after four years of negotiation with a recalcitrant owner. It was the 11th of the 12 stolen apostle mosaics to be located and returned to Cyprus, leaving only St. Mark still on the lam.

Arthur Brand, who runs a firm that specializes in the recovery of looted artworks and stars in a Dutch TV program called The Art Detective which follows his cases, joined the hunt for the Mark mosaic three years ago. With the support of the Church of Cyprus and the Cypriot government, he was able to follow the trail thanks to tips from informants and his own detecting skill. Finally Brand found St. Mark in Monaco.

Arthur Brand, who runs a firm that specializes in the recovery of looted artworks and stars in a Dutch TV program called The Art Detective which follows his cases, joined the hunt for the Mark mosaic three years ago. With the support of the Church of Cyprus and the Cypriot government, he was able to follow the trail thanks to tips from informants and his own detecting skill. Finally Brand found St. Mark in Monaco.

“It was in the possession of a British family, who bought the mosaic in good faith more than four decades ago,” Mr Brand said.

“They were horrified when they found out that it was in fact a priceless art treasure,” Mr Brand said.[…]

The family agreed to return it “to the people of Cyprus” in return for a small fee to cover restoration and storage costs, he added.

Arthur Brand recovered the mosaic from Monaco last week. On Friday, November 16th, he formally returned it to the Embassy of Cyprus in The Hague, The Netherlands. On Sunday, November 18th, St. Mark was home. That leaves only one piece of the Panagia Kanakaria mosaics still missing: the feet of Christ. Brand is on it.