The skeleton of a horse who died wearing an elaborate harness and saddle have been unearthed at an elite villa on the outskirts of Pompeii. This is the third set of horse remains discovered at the estate north of the city walls, the first of which was the first confirmed horse ever found at Pompeii.

The skeleton of a horse who died wearing an elaborate harness and saddle have been unearthed at an elite villa on the outskirts of Pompeii. This is the third set of horse remains discovered at the estate north of the city walls, the first of which was the first confirmed horse ever found at Pompeii.

Excavations began last March as an emergency response to looting activity. Tunnels dug underneath the villa by thieves were endangering the archaeological material. The dig brought to light a series of service areas of the grand suburban villa with artifacts preserved in exceptional condition. Amphorae, cooking utensils, even parts of a wooden bed were recovered, and a plaster cast was made of the entire bed.

One of the service areas that could be identified is the stable. Archaeologists unearthed the first horse lying on its side and were able to make a plaster cast from the cavity the horse’s body had left in the hardened volcanic rock. They then unearthed the legs of a second horse. This year the team excavated the rest of the stable, revealing the rest of the remains of the second horse and the skeleton of a third complete with its harness.

One of the service areas that could be identified is the stable. Archaeologists unearthed the first horse lying on its side and were able to make a plaster cast from the cavity the horse’s body had left in the hardened volcanic rock. They then unearthed the legs of a second horse. This year the team excavated the rest of the stable, revealing the rest of the remains of the second horse and the skeleton of a third complete with its harness.

The former was found lying on its right side, skull on top of the left front leg. It was next to charred wood pieces from a manger (also cast in plaster). The position suggests that the poor horse was tied to it and could not get away when Vesuvius’ pyroclastic fury hit the stable. The third horse was found on its left side, an iron bit clenched between its teeth. The looting tunnels exposed the cavity and cementified it made it impossible to make a plaster cast of it.

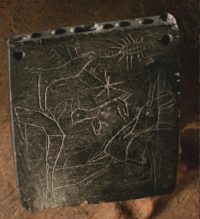

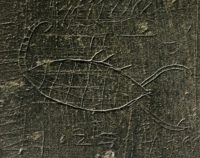

The excavation of the third horse revealed five bronze objects: four wood pieces of half-moon shape coated in bronze found on the ribs, one bronze piece made of three hooks riveted to a ring connected to a disc. It was found under the belly near the front legs. The shapes and design of these parts suggest they were part of a saddle that is described in ancient sources. It was a wooden structure with four horns, two in the front, two in the rear, covered with bronze plates. This firm saddle gave the rider stability in an era before stirrups.

The excavation of the third horse revealed five bronze objects: four wood pieces of half-moon shape coated in bronze found on the ribs, one bronze piece made of three hooks riveted to a ring connected to a disc. It was found under the belly near the front legs. The shapes and design of these parts suggest they were part of a saddle that is described in ancient sources. It was a wooden structure with four horns, two in the front, two in the rear, covered with bronze plates. This firm saddle gave the rider stability in an era before stirrups.

Saddles of this kind were used from the early imperial era particularly by members of the military. The ring junction, four for each harness, were used to connect leather straps to the saddle horns. This was rich, expensive tack that would have belonged to someone of very high rank. The artifacts found strongly indicate that this horse belonged to a Roman military officer and had been saddled likely in the hope of escaping the eruption. Vesuvius got to human and equines before they had a chance.