Greek historian Herodotus has had an enduring reputation for indulging in well, let’s just call them embellishments, ever since he wrote The Histories in the 5th century B.C. I fondly recall my 7th grade Social Studies teacher calling him Herodotus the Liar, and scholars have alternately referred to him as the Father of History and the Father of Lies. So even descriptions of things he claimed to have witnessed personally are taken with a grain of salt. His voyage to Egypt, for example, documented in Book II (Euterpe) of The Histories, has been subject of vigorous debate among historians. A number of them have questioned whether he ever stepped foot in the country given how many dubious statements are in his account.

One of those accounts has now been archaeologically verified for the first time. A shipwreck discovered in the sunken city of Thonis-Heraclion fits Herodotus’ detailed description of the construction of a “baris” vessel, a type of trading vessel that was widespread in Egypt. Here the ship as Herodotus saw it built:

One of those accounts has now been archaeologically verified for the first time. A shipwreck discovered in the sunken city of Thonis-Heraclion fits Herodotus’ detailed description of the construction of a “baris” vessel, a type of trading vessel that was widespread in Egypt. Here the ship as Herodotus saw it built:

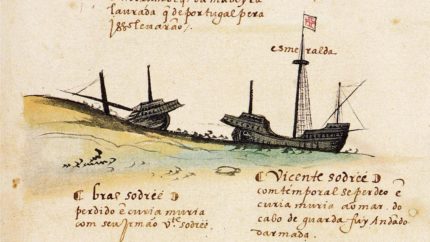

The vessels used in Egypt for the transport of merchandise are made of the Acantha (Thorn), a tree which in its growth is very like the Cyrenaic lotus, and from which there exudes a gum. They cut a quantity of planks about two cubits in length from this tree, and then proceed

to their ship-building, arranging the planks like bricks, and attaching them by ties to a number of long stakes or poles till the hull is complete, when they lay the cross-planks on the top from side to side. They give the boats no ribs, but caulk the seams with papyrus on the

inside. Each has a single rudder, which is driven straight through the keel. The mast is a piece of acantha-wood, and the sails are made of papyrus. These boats cannot make way against the current unless there is a brisk breeze; they are, therefore, towed up-stream from the shore: down-stream they are managed as follows. There is a raft belonging to each, made of the wood of the tamarisk, fastened together with a wattling of reeds; and also a stone bored through the middle about two talents in weight. The raft is fastened to the vessel by a rope, and allowed to float down the stream in front, while the stone is attached by another rope astern. The result is that the raft, hurried forward by the current, goes rapidly down the river, and drags the

“baris” (for so they call this sort of boat) after it; while the stone, which is pulled along in the wake of the vessel, and lies deep in the water, keeps the boat straight. There are a vast number of these vessels in Egypt, and some of them are of many thousand talents’ burthen.

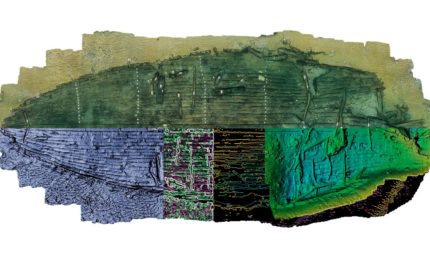

The wreck, number 17 of more than 70 vessels that have been discovered at the Thonis-Heracleion site, is larger than the one described by Herodotus. It was an estimated 28 meters (92 feet) long when intact, one of the largest ancient Egyptian trading vessels ever found. Its crescent-shaped hull made of thick planks joined with tenons matches Herodotus’ description very well.

The wreck, number 17 of more than 70 vessels that have been discovered at the Thonis-Heracleion site, is larger than the one described by Herodotus. It was an estimated 28 meters (92 feet) long when intact, one of the largest ancient Egyptian trading vessels ever found. Its crescent-shaped hull made of thick planks joined with tenons matches Herodotus’ description very well.

[Director of Oxford University’s Centre for Maritime Archaeology Dr. Damian] Robinson added: “Herodotus describes the boats as having long internal ribs. Nobody really knew what that meant… That structure’s never been seen archaeologically before. Then we discovered this form of construction on this particular boat and it absolutely is what Herodotus has been saying.”

About 70% of the hull has survived, well-preserved in the Nile silts. Acacia planks were held together with long tenon-ribs – some almost 2m long – and fastened with pegs, creating lines of ‘internal ribs’ within the hull. It was steered using an axial rudder with two circular openings for the steering oar and a step for a mast towards the centre of the vessel.

Robinson said: “Where planks are joined together to form the hull, they are usually joined by mortice and tenon joints which fasten one plank to the next. Here we have a completely unique form of construction, which is not seen anywhere else.”