A vast quantity of vessels used for feasting, many of them imports, have been unearthed from Celtic settlements and graves. The large numbers, origins and distribution of the feasting vessels have primarily been interpreted as evidence that the Celtic elite was imitating the Mediterranean practice of wine banquets, mimicking the lifestyle of southern elites north of the Alps. To determine what the Celts were actually consuming in those fine imported vessels, a research team led by scientists from Ludwig-Maximilians-Universitaet (LMU) in Munich and the University of Tübingen embarked on a large-scale examination of organic residues inside the feasting vessels.

A vast quantity of vessels used for feasting, many of them imports, have been unearthed from Celtic settlements and graves. The large numbers, origins and distribution of the feasting vessels have primarily been interpreted as evidence that the Celtic elite was imitating the Mediterranean practice of wine banquets, mimicking the lifestyle of southern elites north of the Alps. To determine what the Celts were actually consuming in those fine imported vessels, a research team led by scientists from Ludwig-Maximilians-Universitaet (LMU) in Munich and the University of Tübingen embarked on a large-scale examination of organic residues inside the feasting vessels.

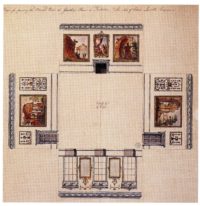

The team focused on artifacts found at one the most significant Early Iron Age sites in Western Central Europe: Vix-Mont Lassois in Burgundy, France. The site is best known for the intact princely grave unearthed in 1953 that contained the Vix Krater, an imported Greek bronze volute krater of such gargantuan proportions that at 5’4″ high, 450 lbs in weight and with a capacity of 1,100 liters, it is the largest surviving metal vessel from antiquity. Excavations have recovered hundreds of fragments of Mediterranean pottery, mainly Attic black- and red-figure, amphorae from the Greek colony of Marseille and a broad variety of other imported Mediterranean vessels.

The team focused on artifacts found at one the most significant Early Iron Age sites in Western Central Europe: Vix-Mont Lassois in Burgundy, France. The site is best known for the intact princely grave unearthed in 1953 that contained the Vix Krater, an imported Greek bronze volute krater of such gargantuan proportions that at 5’4″ high, 450 lbs in weight and with a capacity of 1,100 liters, it is the largest surviving metal vessel from antiquity. Excavations have recovered hundreds of fragments of Mediterranean pottery, mainly Attic black- and red-figure, amphorae from the Greek colony of Marseille and a broad variety of other imported Mediterranean vessels.

Organ residue analysis was performed on 99 vessels, 16 imported and 83 locally made. Of the local production, 68 are fine ware, high quality vessels on a par with the imports, and 15 are coarse ware. The vessels include both low forms — drinking cups, bowls and beakers — and high forms — amphorae and kraters used for transporting or mixing large quantities.

Organ residue analysis was performed on 99 vessels, 16 imported and 83 locally made. Of the local production, 68 are fine ware, high quality vessels on a par with the imports, and 15 are coarse ware. The vessels include both low forms — drinking cups, bowls and beakers — and high forms — amphorae and kraters used for transporting or mixing large quantities.

The finds included pottery and bronze vessels that had been imported from Greece around 500 BCE. “This was a period of rapid change, during which vessels made in Greece and Italy reached the region north of the Alps in large numbers for the first time. It has generally been assumed that this indicates that the Celts began to imitate the Mediterranean lifestyle, and that only the elite were in a position to drink Mediterranean wine during their banquets,” says LMU archaeologist Philipp Stockhammer, who led the project. “Our analyses confirm that they indeed consumed imported wines, but they also drank local beer from the Greek drinking bowls. In other words, the Celts did not simply adopt foreign traditions in their original form. Instead, they used the imported vessels and products in their own ways and for their own purposes. Moreover, the consumption of imported wine was apparently not confined to the upper echelons of society. Craftsmen too had access to wine, and the evidence suggests that they possibly used it for cooking, while the elites quaffed it in the course of their drinking parties. The study shows that intercultural contact is a dynamic process and demonstrates how easy it is for unfamiliar vessels to serve new functions and acquire new meanings.”

Chemical analysis of the food residues absorbed into the ancient pots now makes it possible to determine what people ate and drank thousands of years ago. The group of authors based at the University of Tübingen analyzed these chemical fingerprints in the material from Mont Lassois. “We identified characteristic components of olive oil and milk, imported wine and local alcoholic beverages, as well as traces of millet and beeswax,” says Maxime Rageot, who performed the chemical analyses in Tübingen. “These findings show that – in addition to wine – beers brewed from millet and barley were consumed on festive or ritual occasions.” His colleague Cynthianne Spiteri adds: “We are delighted to have definitively solved the old problem of whether or not the early Celts north of the Alps adopted Mediterranean drinking customs. – They did indeed, but they did so in a creative fashion!”

That is more than borne out by the combination of and customization of the vessels found in elite graves, most recently the princely tomb unearthed in Lauvau, Champagne, in 2015. Among the exceptional grave goods were a wine feasting service that included an Attic black figure ceramic oinochoe. The oinochoe was made in Greece, rimmed with gold decorated in Etruscan motifs and silver elements with Celtic designs. The bronze cauldron found in the Prince of Lavau’s grave is of Etruscan manufacture and is the second largest known surviving metal vessel from antiquity.

That is more than borne out by the combination of and customization of the vessels found in elite graves, most recently the princely tomb unearthed in Lauvau, Champagne, in 2015. Among the exceptional grave goods were a wine feasting service that included an Attic black figure ceramic oinochoe. The oinochoe was made in Greece, rimmed with gold decorated in Etruscan motifs and silver elements with Celtic designs. The bronze cauldron found in the Prince of Lavau’s grave is of Etruscan manufacture and is the second largest known surviving metal vessel from antiquity.

The study has been published in the open access journal PLOS ONE.