A cross-section model of HMS Victory, Admiral Nelson’s valiant flagship at the Battle of Trafalgar, has been acquired by a descendant of the man who originally designed the warship. Sir Benjamin Slade, 7th Baronet, bought the model at auction on January 8th for £450 (plus buyers premium) and took it home to Maunsel House, the family estate in Bridgwater, Somerset, where it joins two other models of Victory on display there.

A cross-section model of HMS Victory, Admiral Nelson’s valiant flagship at the Battle of Trafalgar, has been acquired by a descendant of the man who originally designed the warship. Sir Benjamin Slade, 7th Baronet, bought the model at auction on January 8th for £450 (plus buyers premium) and took it home to Maunsel House, the family estate in Bridgwater, Somerset, where it joins two other models of Victory on display there.

Thomas Slade, Surveyor of the Navy, designed HMS Victory in 1759. The hull was completed in 1760 but the ship wasn’t launched until 1765, giving the wood of its hull years to season when usually ships only got a few months. That may have played a role in its longevity. Victory is the most successful first-rate ship of the line ever built. Slade died in 1771, decades before the ship he’d designed would rise to international fame at the Battle of Trafalgar in 1805.

Victory was an inauspicious name, to put it mildly. The previous HMS Victory sank in a storm off the Channel Islands in 1744, only seven years after its launch. All 1,150 crewmen were lost. The Victory before that one had burned down in an accidental fire in 1721. Still, for whatever reason, likely because it was the only proposed name not in use, the 104-gun first-rate ship of the line was dubbed Victory and in the course of a most illustrious naval career redeemed the name for all time.

The Napoleonic Wars also advanced the fortunes of the Slade family. The 1st Baronet, Sir John “Black Jack” Slade, was given the title in 1831 in honor of his military accomplishments primarily during the Peninsular War, although he was held in active contempt by the Duke of Wellington and many of his subordinates.

The current Baronet is pretty much the Platonic form of that most deferential of euphemisms, the “eccentric millionaire.” Earlier this year the 73-year-old went on a matchmaking reality TV series to find a wife who “must be able to breed two sons” in exchange for him “showering [her] in jewels” and giving her £50,000 a month “pocket money.” Absolutely no Scorpios allowed. The year before that he featured on another reality show when bailiffs showed up at his door demanding payment on an unpaid £4,700 bill owed to, ironically, a wedding planner. Also he owns a peacock that attacked a Lexus because, Slade thinks, the peacock is gay and was attracted to the blue of the vehicle, thus forcing Slade to ban peacock blue Lexuses from Maunsel House and inspiring the truly great headline: Baronet Claims Peacock Sexually Attacked Car.

On the plus side, last year he offered to donate 50 old growth oak trees from his estate for the reconstruction of Notre Dame after the devastating fire of April 2019, a gesture that he hoped would make ammends for all the generations of Slades who went at the French with such deadly gusto.

Apparently he didn’t realize he was buying a cross-section model of HMS Victory and thought it was a full version to scale like the one five feet long that was gifted to his family by the Royal Navy in the 19th century. The dimensions are clearly stated on the catalogue page and it’s not like you can’t tell it’s a section from the picture. You literally see through it. That’s a large part of its charm, in fact, that you can see all the wee cannons and barrels and ballast and whatnot.

Apparently he didn’t realize he was buying a cross-section model of HMS Victory and thought it was a full version to scale like the one five feet long that was gifted to his family by the Royal Navy in the 19th century. The dimensions are clearly stated on the catalogue page and it’s not like you can’t tell it’s a section from the picture. You literally see through it. That’s a large part of its charm, in fact, that you can see all the wee cannons and barrels and ballast and whatnot.

“It is a bit like ordering a birthday cake online and then only getting a slice. To think that I was worried that it would not fit in my car. Well, the joke is on me, that’s for sure.

“To be honest I was prepared to pay a lot more – I got a bit of a bargain in the end. It was much smaller than I thought it would be. It’s pretty tiny. Online it looked bigger.

“It one of those small models which lets you actually see a cross section and everything that went on inside the ship. I might put it on my bar.”

As long as he keeps the peacock away from it.

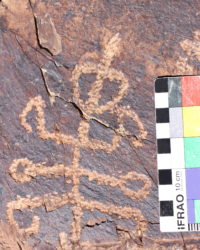

An unusual praying mantis petroglyph has been found at the Teymareh rock art site in central Iran. The carved image 5.5 inches long and 4.3 inches wide was discovered during a 2017-2018 survey by archaeologists. Its precise age is unknown because radiocarbon dating cannot be performed in Iran due to international sanctions, but the rock art at the site ranges in age from 40,000 to 4,000 years old.

An unusual praying mantis petroglyph has been found at the Teymareh rock art site in central Iran. The carved image 5.5 inches long and 4.3 inches wide was discovered during a 2017-2018 survey by archaeologists. Its precise age is unknown because radiocarbon dating cannot be performed in Iran due to international sanctions, but the rock art at the site ranges in age from 40,000 to 4,000 years old. depicted in petroglyphs, so the archaeologists collaborated with entomologists to identify the creature from its morphological features. Its six legs, large triangular head with extended vertex, curved hind legs and bent forelimbs marked it as a mantid. Iran’s Empusa genus, which inhabits hot, dry environments like the Teymareh Region, have the expanded vertex seen in the petroglyph.

depicted in petroglyphs, so the archaeologists collaborated with entomologists to identify the creature from its morphological features. Its six legs, large triangular head with extended vertex, curved hind legs and bent forelimbs marked it as a mantid. Iran’s Empusa genus, which inhabits hot, dry environments like the Teymareh Region, have the expanded vertex seen in the petroglyph.