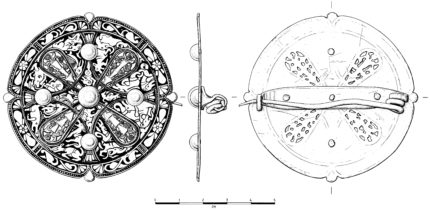

A Viking grave has been discovered under the floor of a private home in Bodø, central Norway. The Kristensens were renovating the family home and pulled the floorboards to install new insulation under the bedroom floor. After digging up a layer of sand and the stone rubble underneath that, something shiny caught their eye. At first they thought the small dark circular object might be the wheel from an old toy. A little more digging turned up a heavily corroded iron axe and a few other iron pieces.

A Viking grave has been discovered under the floor of a private home in Bodø, central Norway. The Kristensens were renovating the family home and pulled the floorboards to install new insulation under the bedroom floor. After digging up a layer of sand and the stone rubble underneath that, something shiny caught their eye. At first they thought the small dark circular object might be the wheel from an old toy. A little more digging turned up a heavily corroded iron axe and a few other iron pieces.

At this point Mariann Kristensen contacted Nordland County officials and they dispatched archaeologists from the Tromsø Museum to investigate the finds. The bead, axe and other objects appear to date to the early Middle Ages, around 950-1050 A.D. They have been transferred to the museum for study and conservation.

Archaeologists have begun a larger excavation of the find site; ie, under the Kristensens’ house. County archaeologist Martinus Hauglid thinks it’s most likely a grave from the Iron Age or Viking Age. The stones the Kristensens found under the sand layer are probably part of a burial cairn.

[Hauglid] said he had never heard of a find being made underneath a house.

“I never heard of anything like that and I’ve been in business for nearly 30 years,” he said. “They did a magificent job, they reported it to use as soon as they got the suspicion that it actually was something old.

The house had been in the family since it was built by Mariann’s great-grandfather in 1914. There is no family legend of Vikings in eternal slumber under the bedroom floor.