We know from historical sources and extant legal codes that the Anglo-Saxons practiced intentional facial mutilation as punishment, both by judicial decree and by societal custom, but because cutting off ears, noses and lips mainly affects the soft tissues, there have been no confirmed instances of it on the archaeological record. A new study of a previously unexamined cranium discovered in the 1960s has found the first direct evidence of formal facial mutilation.

We know from historical sources and extant legal codes that the Anglo-Saxons practiced intentional facial mutilation as punishment, both by judicial decree and by societal custom, but because cutting off ears, noses and lips mainly affects the soft tissues, there have been no confirmed instances of it on the archaeological record. A new study of a previously unexamined cranium discovered in the 1960s has found the first direct evidence of formal facial mutilation.

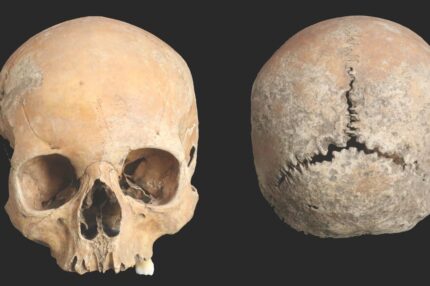

The cranium was found during a salvage excavation before construction of a housing estate in Basingstoke, England. It was unearthed accidentally by a mechanical digger working on a drainage pit and discovered in the spoil. Because the context had been disturbed, there was no additional information — no other skeletal remains, no archaeological material — to indicate if this was an inhumation burial or a head alone, perhaps displayed after decapitation. It certainly was not a cemetery burial in consecrated ground. Full body or head alone, the deceased was deliberately outcast.

For decades the cranium was held in storage by the Hampshire Cultural Trust. Researchers from University College London’s Institute of Archaeology have now analyzed it for the first time. Thankfully it had never been cleaned, and the silt from its burial context still lined the interior. That silt was specific enough to pinpoint its original location as a spot on the east side of the drainage pit. Radiocarbon dating of the skull provides a likely date range of 776–899 A.D.

Osteological examination found the cranium belonged to a young person. Most of the teeth were lost over the centuries, but of the three remaining, two were unerupted. Two of the skull sutures were unfused; one was only  beginning to fuse. Based on these features, researchers determined the individual was between 15 and 18 years of age at time of death. DNA analysis revealed that the cranium belonged to a young woman. Stable isotope analysis of the teeth was unable to identify where she was born and raised, beyond indicating that she was not local to the area.

beginning to fuse. Based on these features, researchers determined the individual was between 15 and 18 years of age at time of death. DNA analysis revealed that the cranium belonged to a young woman. Stable isotope analysis of the teeth was unable to identify where she was born and raised, beyond indicating that she was not local to the area.

There was significant peri-mortem trauma to the face: a linear cut on the forehead, angled cuts through the lower edge of the nasal aperture, a linear cut through the side edge of the nose hole, a nick on the right side of the face. These marks were left by a knife slicing from the bottom of the nose halfway up the nasal spine. The nick is from a cut through the lips made a different angle from the nose cut. This poor young woman had her nose and lips cut off, and the cut in the forehead suggests she may have been scalped too, or at least had her hair removed.

The mutilation was intended to punish by humiliation, destroying a woman’s beauty and marking her for life for her transgression. However in this case the injuries were so severe that they likely caused her death.

There can be little doubt that the victim died at the time of—or soon after—the traumatic event. The edges of the wound are sharp with no signs of remodelling that would indicate survival for even a few days afterwards. The injury to the individual’s nose could have been sufficient to cause her death, as the wound would probably have damaged the network of arteries in the back of her nose. Two plexuses of arteries supply the nose with blood (Pope & Hobbs 2005). The anterior one, known as Kiesselbach’s plexus, is responsible for the majority of nose-bleeds, with bleeding easily controlled by applying pressure. Injury to the posterior (Woodruff’s) plexus tends to cause bleeding down the throat, and can only be controlled by packing the rear of the nasal structures above the soft palate—a procedure unlikely to have been known to Anglo-Saxon practitioners. In the present case, the nasal wound probably caused profuse bleeding from the posterior plexus, leading to death by choking. Whether her death resulted directly from the mutilation or from other injuries, however, is unknowable in the absence of the post-cranial skeleton. […]

The specificity of the wounds strongly suggests that her mutilation was punitive, either at the hands of a local mob marking her perceived offence by established custom, or by local administrators applying legal prescription. In either scenario, the woman—or at least her head—was then outcast to the limit of the local territory. As noted above, the isolated nature of the cranium perhaps indicates punishment at the most local level.

The study has been published in the journal Antiquity and can be read here.