There are numerous sources for the funerary rituals and spells Egyptians used to aid the dead over the threshold of the afterlife. They were written on papyrus and linen mummy wrappings, painted on coffins and carved on walls, texts now known collectively as the Book of the Dead. Mummification was an essential part of Egyptian funerary practice, the means by which the body would be able to rejoin the soul in the afterlife, but very little written material detailing the process has survived. Egyptologists believe this was deliberate, that the sacred art was transmitted orally from embalmer to embalmer.

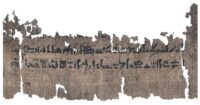

Only two papyri dedicated to mummification were previously known, but now a third has been found in an unexpected context: in the middle of a medical text on herbal treatments and swellings of the skin. Written back and front over 20 feet in length, it is second longest surviving Egyptian  medical papyrus. The Papyrus Louvre-Carlsberg (so named between it is in two parts, one in the collection of the Louvre Museum and the other University of Copenhagen’s Papyrus Carlsberg Collection) dates to around 1450 B.C., which makes it the oldest of the three mummification papyri by a thousand years. It is the earliest known Egyptian herbal treatise. The section on mummification covers details the other two never address.

medical papyrus. The Papyrus Louvre-Carlsberg (so named between it is in two parts, one in the collection of the Louvre Museum and the other University of Copenhagen’s Papyrus Carlsberg Collection) dates to around 1450 B.C., which makes it the oldest of the three mummification papyri by a thousand years. It is the earliest known Egyptian herbal treatise. The section on mummification covers details the other two never address.

University of Copenhagen Egyptologist Sofie Schiødt has translated and interpreted the papyrus for her doctoral dissertation.

“One of the exciting new pieces of information the text provides us with concerns the procedure for embalming the dead person’s face. We get a list of ingredients for a remedy consisting largely of plant-based aromatic substances and binders that are cooked into a liquid, with which the embalmers coat a piece of red linen. The red linen is then applied to the dead person’s face in order to encase it in a protective cocoon of fragrant and anti-bacterial matter. This process was repeated at four-day intervals.”

Although this procedure has not been identified before, Egyptologists have previously examined several mummies from the same period as this manual whose faces were covered in cloth and resin. […]

The importance of the Papyrus Louvre-Carlsberg manual in reconstructing the embalming process lies in its specification of the process being divided into intervals of four, with the embalmers actively working on the mummy every four days.

“A ritual procession of the mummy marked these days, celebrating the progress of restoring the deceased’s corporeal integrity, amounting to 17 processions over the course of the embalming period. In between the four-day intervals, the body was covered with cloth and overlaid with straw infused with aromatics to keep away insects and scavengers,” Sofie Schiødt says.

The papyrus is scheduled to be published in 2022.