CT scans of the mummy of 17th Dynasty pharaoh Seqenenre-Taa-II have revealed new details about his violent death. Seqenenre ruled southern Egypt at the end of the Second Intermediate Period when Egypt was occupied by the Hyksos. His reign was brief — ca. 1558–1553 B.C. — but consequential, as his death in battle helped spur the ultimate defeat of the Hyksos and reunification of Egypt in 1550 B.C. by Seqenenre’s son, founder of the 18th Dynasty Ahmose I.

CT scans of the mummy of 17th Dynasty pharaoh Seqenenre-Taa-II have revealed new details about his violent death. Seqenenre ruled southern Egypt at the end of the Second Intermediate Period when Egypt was occupied by the Hyksos. His reign was brief — ca. 1558–1553 B.C. — but consequential, as his death in battle helped spur the ultimate defeat of the Hyksos and reunification of Egypt in 1550 B.C. by Seqenenre’s son, founder of the 18th Dynasty Ahmose I.

The Hyksos, a Greek version of the Egyptian term for “foreign rulers,” occupied Egypt for about a century. They established their capital in Avaris (present-day Tell el-Dab’a) and directly ruled over Lower and Middle Egypt while extracting tribute from the Egyptian pharaohs who still ruled a much-reduced kingdom centered in Thebes. Simmering tensions finally exploded into all-out war in the reign of Seqenenre.

It all started, as so many deadly conflicts do, with a noise complaint. According to The Quarrel of Apophis and Seqenenre, a sebayt (ancient Egyptian wisdom literature meant to impart lessons) written in the 19th Dynasty, Hyksos king Apophis wrote a deliberately inflammatory letter to Seqenenre demanding that he get rid of a sacred pool of hippopotami in Thebes whose vocalizations were disturbing his sleep 400 miles away. The ending of the fable is lost, but the last surviving fragment of papyrus says Seqenenre called his high officials and every ranking soldier in his army to inform them of Apophis’ provocation, which suggests preparation for war.

Hard archaeological evidence of the 17th Dynasty Hyksos wars is thin on the ground. Inscriptions point to Deir el-Ballas, a settlement north of Thebes founded by Seqenenre, having been used as a staging ground for war, but there is nothing in the record about how it all played out between Seqenenre and the Hyksos, just about how his sons battled them concluding with Ahmose’s victory.

The mummified remains of Seqenenre were discovered at the Deir el-Bahari mortuary complex outside of Thebes in 1881. The mummy was unwrapped five years later at the Cairo Museum. Inscriptions on the linen wrappings identified it as the mummy of Seqenenre-Taa. It was clear from that initial examination that the remains were not mummified in the royal workshops. The mummification was incomplete and the remains had putrefied. Several head wounds were also evident. Later studies noted that there were five distinct head injuries and that there were no wounds anywhere else on the body.

The question whether the wounds and hasty mummification were the result of a death in battle, post-capture execution or palace assassination has been subject of debate since 1886. In 2019, researchers re-examined the mummy of Seqenenre with a CT scanner that allowed them to create a full 3D reconstruction of the body. The imaging data was then compared to five Asian Middle Bronze Age weapons from the Hyksos period that were discovered in Avaris and are now in the collection of the Egyptian Museum. The weapons — three daggers, a battle axe and a spearhead — date to around the reign of Seqenenre, so if they were found to match his wounds, it would be solid evidence that he died at the hands of the Hyksos.

The scans found that the bones within the wrappings were partly disarticulated, but researchers were nonetheless able to estimate his age at death to be around 40 years old and his height to be around 5’5″, give or take an inch. The dessicated remnants of his brain are still present on the left side of his cranium. The usual procedures of mummification removed the brain, but there is no evidence that was even attempted here. The viscera were removed, however, and resins and linen bundles packed into the cavities.

The 3D scan of the head found a profusion of injuries: a massive cut fracture of the frontal bone, a puncture fracture above the right eyebrow, fractures to the nose, right eye socket and right cheekbone caused by blunt trauma. There’s a cut wound on the left cheekbone and a fracture of the left side of the mandible. A fracture in the foramen magnum was caused by a penetrating injury through the back of the skull.

The forehead cut fracture was likely inflicted by a heavy sharp weapon like a sword or battle axe by an assailant who was above Seqenenre, for example, standing above the kneeling king or on horseback while the pharaoh was on foot. The puncture fracture above the right eyebrow was inflicted by a double-edge blade wielded by an assailant standing in front of him slightly to the right. The foramen fracture was inflicted with a long sharp weapon wielded from Seqenenre’s left side. Any one of these blows could have been fatal.

The broken nose, right eye socket and cheekbone were caused by repeated blows with a blunt object like a club or axe handle. He was struck diagonally from above. The left cheek fracture was caused by a heavy blade like a sword or axe. The bronze battle axe fit the size and shape of the wound.

We confirm in this CT study that Seqenenre’s craniofacial injuries were inflicted around the time of the King’s death (perimortem) as there is no evidence of healing. Such severe craniofacial trauma could have caused fatal shock, blood loss, and/or intracranial trauma.

The variety in attack angle, as well the wide range of weapons we believe to have caused the King’s injuries, indicate that Seqenenre was killed in battle by numerous enemy attackers. The match between weapons and the morphology of the injuries strongly suggests that Seqenenre was killed during a war between the Egyptians and the Hyksos.

Typically, when people suffer such massive injuries to the face, there are defensive wounds to the arm because people reflexively put their arms up to ward off the blows. There are no such injuries to Seqenenre’s arms, but his hands are flexed at the wrist and the fingers are stiff. Researchers believe they were tied together behind his back when he died, and the muscles became rigid in that position.

We argue that Seqenenre fought the Hyksos, was captured, and that his hands were cuffed.[…] We assume that the King was at a lower position than his assailant(s), possibly kneeling at least for some time during the attack. This position explains the high forehead injury that could have been the first blow the king received, inflicted by a sword or an ax. The strong hit must have caused the King to fall down, possibly on his back. The King may have received several attacks from the assailant with the Hyksos battle ax, possibly using its blade to inflict the fracture above the right eyebrow (right supra-orbital). Then a thick stick (possibly the handle of the ax) was used to smash the nose and the right eye of the King. The assailant hit the King’s left side of the face with the ax. Another assailant at the left side used a spear horizontally to pierce deeply the lower part of the left ear (mastoid) and reached the foramen magnum. We assume that the King was dead at this point, and that his body was rolled to lie at his left side where he received several blows to the right side of the skull possibly by a dagger. The dead King likely stayed lying down on his left side for some time enough for the body to start decomposition as the brain shifted to this dependent side.

A rare Roman millstone engraved with a phallus was discovered during highway expansion work in Cambridgeshire. It was unearthed in 2017-2018, but the was the phallus relief was not recognized until post-excavation cleaning and documentation. As utilitarian objects, millstones were rarely decorated. Of the 20,000 archaeological millstones and querns unearthed in Britain, only four are decorated.

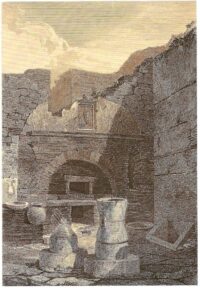

A rare Roman millstone engraved with a phallus was discovered during highway expansion work in Cambridgeshire. It was unearthed in 2017-2018, but the was the phallus relief was not recognized until post-excavation cleaning and documentation. As utilitarian objects, millstones were rarely decorated. Of the 20,000 archaeological millstones and querns unearthed in Britain, only four are decorated. The phallic symbol’s most obvious connotation was fertility which was bound to the idea of proliferation, fecundity, productivity. Thus a phallus played multiple roles for a business. It warded off evil while drawing in luck, happiness and prosperity. Pompeii provides a stellar example of this confluence in the carved relief of a phallus with the inscription “His Habitat Felicitas” found above a bakery. Felicitas means both happiness (as in “felicitations!”) and luck (as in “felicitous”), from the root word “felix” meaning “fertile.” There’s an additional layer of association between the phallus as inseminator and grains, themselves symbols of fecundity.

The phallic symbol’s most obvious connotation was fertility which was bound to the idea of proliferation, fecundity, productivity. Thus a phallus played multiple roles for a business. It warded off evil while drawing in luck, happiness and prosperity. Pompeii provides a stellar example of this confluence in the carved relief of a phallus with the inscription “His Habitat Felicitas” found above a bakery. Felicitas means both happiness (as in “felicitations!”) and luck (as in “felicitous”), from the root word “felix” meaning “fertile.” There’s an additional layer of association between the phallus as inseminator and grains, themselves symbols of fecundity.