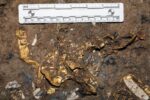

Archaeologists have discovered a mural depicting the spider god of the pre-Hispanic Cupisnique culture in the Lambayeque region of northern Peru. The mural was applied to the mud brick wall 50 feet wide 16 feet of a sacred structure. It was painted in ochre, yellow, grey against a white background. It’s hard to make out now that so much of it is lost, but the yellow zig-zag bits are the legs of the spider god. The vertical ochre stripe down the middle of the legs is the abdomen. The ochre gum-drop shape surrounded by a yellow boundary and topped by a blue rectangle is interpreted as the hilt of a knife or dagger.

Archaeologists have discovered a mural depicting the spider god of the pre-Hispanic Cupisnique culture in the Lambayeque region of northern Peru. The mural was applied to the mud brick wall 50 feet wide 16 feet of a sacred structure. It was painted in ochre, yellow, grey against a white background. It’s hard to make out now that so much of it is lost, but the yellow zig-zag bits are the legs of the spider god. The vertical ochre stripe down the middle of the legs is the abdomen. The ochre gum-drop shape surrounded by a yellow boundary and topped by a blue rectangle is interpreted as the hilt of a knife or dagger.

The spider god was associated with rainfall, fertility and hunting. Archaeologist Régulo Franco Jordán hypothesizes that this temple, which was built close to the river, was dedicated to water deities.

“The spider on the shrine is associated with water and was an incredibly important animal in pre-Hispanic cultures, which lived according to a ceremonial calendar. It’s likely that there was a special, sacred water ceremony held between January and March when the rains came down from the higher areas.”

The Cupisnique occupied the northern coast of Peru between around 2000 and 500 B.C., and several of their adobe temples have been discovered in Lambayeque. Unfortunately callous agricultural expansion has taken an enormous toll on the region’s irreplaceable cultural heritage. The Early Cupisnique brick temple at Ventarrón was consumed in a fire set by farmers burning their sugar cane fields. Its murals, radiocarbon dated to 2000 B.C., the oldest absolutely dated mural art in the Americas, were completely destroyed.

The recently-discovered huaca, dubbed Tomabalito, also suffered extensive damage when neighboring farmers attempted to expand their avocado and sugar cane cultivation. Using earthmovers, they leveled an estimated 60% of the ancient temple complex. The existence of the temple only came to light in November 2020, when Régulo Franco Jordán, discoverer of the Lady of Cao burial, was informed of the appearance of monumental mural. He inspected the find himself, and identified it as a Cupisnique construction based on the characteristic conical adobe used to make the wall. He believes it’s about 3,200 years old.

The recently-discovered huaca, dubbed Tomabalito, also suffered extensive damage when neighboring farmers attempted to expand their avocado and sugar cane cultivation. Using earthmovers, they leveled an estimated 60% of the ancient temple complex. The existence of the temple only came to light in November 2020, when Régulo Franco Jordán, discoverer of the Lady of Cao burial, was informed of the appearance of monumental mural. He inspected the find himself, and identified it as a Cupisnique construction based on the characteristic conical adobe used to make the wall. He believes it’s about 3,200 years old.

Jordán reported the discovery to regional cultural heritage authorities who initiated an emergency archaeological intervention. The aim for now is to conserve what’s left of the mural and of the site. While archaeologists are investigating, authorities have applied for the area to be declared a protected site. They have also filed a complaint against the people who bulldozed the site.

Jordán reported the discovery to regional cultural heritage authorities who initiated an emergency archaeological intervention. The aim for now is to conserve what’s left of the mural and of the site. While archaeologists are investigating, authorities have applied for the area to be declared a protected site. They have also filed a complaint against the people who bulldozed the site.