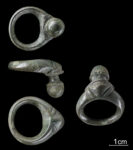

A 350-year-old ring discovered on the Isle of Man may be a mourning ring dedicated to James Stanley, 7th Earl of Derby and Lord of Man. The ring is gold with cut crystal stone on top. Embedded in the center underneath the stone are the initials “JD” spelled out in gold thread. Its style marks it as a Stuart-era mourning ring and it dates to the mid-1600s.

Allison Fox, Curator for Archaeology at Manx National Heritage said:

“The ring is small and quite delicate in form, but of a high quality and intact. The quality suggests that it was made for, or on behalf of, an individual of high status. It is unlikely that we will be able to establish for certain who owned the ring or whom it commemorated, but there is a possibility that it may have been associated with the Stanley family, previously Lords of Man.

The initials JD may refer to James Stanley, 7th Earl of Derby and Lord of Man, a supporter of the Royalist cause in the Civil War. Letters and documents from the time show that he signed his named as J Derby, so the initials JD would be appropriate for him.”

James Stanley wasn’t very involved in the political conflicts between Parliamentarians and Royalists, but when war broke out in 1642, he dedicated himself to the Royalist cause, commanding troops in many battles, most of which he lost. He was with Charles Stuart, son of the decapitated king, in September 1651 at the Battle of Worcester, the final battle of the English Civil War. He was captured as he made his way north after the defeat at Worcester and a month later was tried for treason on the grounds that he had corresponded Charles Stuart, an act that had just been classified as treason in legislation passed a month earlier. He was easily convicted and executed.

Charlotte de La Trémoille was a formidable Royalist in her own right. She held Lathom House, the last Royalist castle still standing in Lancashire, when it was besieged by Parliamentary troops in 1644. On the grounds that it would dishonor her husband, she refused the order to surrender. Instead she fortified the castle to withstand repeated bombardments and placed sharpshooters in strategic locations to pick off enemy soldiers. Lady Derby kept the wolves at bay for more than three months until Royalist forces arrived and broke the siege of Lathom House.

Charlotte was evacuated to Isle of Man for her own safety. She lived there, occasionally joined by Stanley when he wasn’t fighting in England, for the next seven years. After James Stanley’s capture in 1651, he wrote in a letter to his wife that the king was dead, the cause lost and might as well barter the Isle of Man to the Parliamentarians in return for the best possible outcome for him and his family, hopefully including his freedom. She tried but it didn’t work. The Parliamentarians negotiated with Manx rebels instead and Stanley was beheaded. The mourning ring, if it is Derby-related, would have been made at this time and given to a loved one of the deceased to remember him by.

Lady Derby was forced to surrender her two castles on the island to the rebels and was imprisoned. Her heavy losses and her and her husband’s efforts in the Royalist cause did not win her much gratitude from Charles II even after the restoration. She retired to Knowsley Hall, seat of the Earls of Derby, and died in 1668.