Researchers have discovered the first known evidence of ear surgery in a 5,300-year-old skull from the Dolmen of El Pendón, a megalithic tomb monument in the province of Burgos, north central Spain. The study has been published in the journal Scientific Reports.

Researchers have discovered the first known evidence of ear surgery in a 5,300-year-old skull from the Dolmen of El Pendón, a megalithic tomb monument in the province of Burgos, north central Spain. The study has been published in the journal Scientific Reports.

Radiocarbon analysis has determined that the dolmen was built at the beginning of the 4th millennium B.C. It consists of a central funerary chamber with a long entrance passage. The enclosure was created with large standing stones around which a mound, now gone, was built out of stone and soil that was originally more than 80 feet in diameter.

A second phase of use in the last quarter of the 4th millennium B.C. saw the transformation of the funerary chamber into a collective burial ground and ossuary. About 100 bodies were added to the chamber over the next few centuries. Bodies were disarticulated and the remains repositioned, mixing up the skeletal remains. It was not a haphazard scattering. At least 15 different groupings of skulls and pelvises were found.

By the end of the millennium, only six of the original limestone megaliths were still standing, the entrance passage structures were gone and the former mound was just a few feet in diameter. At this point its funerary uses were over, but the site was still revered as a ceremonial and community center.

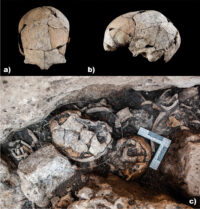

In July of 2018, archaeologists unearthed a skull from the second phase of funerary use at the Dolmen of El Pendón. It was broken and missing some parts, but the neurocranium was complete and in place, as were the nasal bone, cheek bones and lower maxilla. The skull was found lying on its right side facing the entrance of the burial chamber. Examination of the skull revealed that it belonged to a woman, likely of advanced age as she had lost all of her teeth and her thyroid cartilage was fully ossified.

In July of 2018, archaeologists unearthed a skull from the second phase of funerary use at the Dolmen of El Pendón. It was broken and missing some parts, but the neurocranium was complete and in place, as were the nasal bone, cheek bones and lower maxilla. The skull was found lying on its right side facing the entrance of the burial chamber. Examination of the skull revealed that it belonged to a woman, likely of advanced age as she had lost all of her teeth and her thyroid cartilage was fully ossified.

Osteological examination and CT scans found that the external auditory canals of both ears had been enlarged. The edges of the cavities are smooth with no fractures or calluses. These cavities were enlarged by trepanation, the oldest surgical technique on the archaeological record. Seven cut marks on the edge of the trepanation cavity on the left ear are further evidence of surgical intervention. Given the early date of this find, metal was not involved here. The trepanation and the cuts were done with stone tools.

The inner surfaces of the cavities show evidence of the bone resorption changes often seen in mastoiditis, an infection of the mastoid bone just behind the ear, and in mastoid abscesses. An untreated middle ear infection can easily spread to the porous, honeycomb-like mastoid bone, and before the advent of antibiotics, mastoiditis from ear infections was a leading cause of death in children who are more prone to middle ear infections. The damage suffered in this skull, however, lacks the features seen in childhood ear infections. This was a recent illness.

Evidence of ear bone damage from mastoiditis or abscesses has been found before in ancient skulls, but there were no signs of any attempted surgical intervention nor of bone regrowth after recovery. This skull shows clear evidence of bone regeneration and remodeling.

The hypothesis proposed in this research is that the individual to whom the skull belonged was probably surgically intervened on both ears, with an undetermined period between both interventions. Based on the differences in bone remodelling between the two temporals, it appears that the procedure was first conducted on the right ear, due to an ear pathology sufficiently alarming to require an intervention, which this prehistoric woman survived. Subsequently, the left ear would have been intervened; however, it is not possible to determine whether both interventions were performed back-to-back or several months, or even years had passed. It is thus the earliest documented evidence of a surgery on both temporal bones, and, therefore, most likely, the first known radical mastoidectomy in the history of humankind.