A funerary bundle discovered in a tomb from the Middle Sicán period (900-1050 A.D.) at the Huaca Las Ventanas archaeological site in the Lambayeque region of Peru, has been found to include a set of surgical tools indicating the deceased was a surgeon. This is the first such find ever made in Lambayeque or in northern Peru.

A funerary bundle discovered in a tomb from the Middle Sicán period (900-1050 A.D.) at the Huaca Las Ventanas archaeological site in the Lambayeque region of Peru, has been found to include a set of surgical tools indicating the deceased was a surgeon. This is the first such find ever made in Lambayeque or in northern Peru.

Funerary bundle No. 77 was unearthed by archaeologists from the Sicán National Museum in a 2010-2011 excavation of the southern necropolis of Huaca Las Ventanas. It was removed along with its soil and sand context to protect it from being eroded and washed away in flooding from the adjacent La Leche River.

The recovered material was transported to the museum where it was stored for later excavation. That turned out to be much later, a decade later, to be exact, when a National Geographic Donation Fund grant made to the museum in 2021 made it possible to fully explore Bundle No. 77.

The excavation took place between October 2021 and January of this year. Inside the bundle was a gold mask painted with cinnabar, a large bronze pectoral, gilt copper bowls and a poncho-like garment with copper plates. Under the poncho was a pottery vessel with a double spout and a curved bridge handle with a small figure at the apex representing the Huaco Rey (Huaco King).

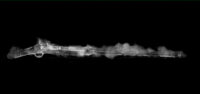

The surgical kit was of particular interest to archaeologists. It is large, containing a full set of awls, needles and knives of various sizes and configurations. There are about 50 knives in total, some with a single cutting edge. Most are a bronze alloy with high arsenic content. Some have wooden handles. There is also a tumi, a ceremonial knife with a half-moon blade. By the tumi was a metal planchette with a symbol associated with surgical instruments. Two frontal bones, one adult and one juvenile, were found next to the planchette. Marks on the bones indicate they were deliberately cut with trepanation techniques. This confirmed that the tools were intended for use in surgery.

The surgical kit was of particular interest to archaeologists. It is large, containing a full set of awls, needles and knives of various sizes and configurations. There are about 50 knives in total, some with a single cutting edge. Most are a bronze alloy with high arsenic content. Some have wooden handles. There is also a tumi, a ceremonial knife with a half-moon blade. By the tumi was a metal planchette with a symbol associated with surgical instruments. Two frontal bones, one adult and one juvenile, were found next to the planchette. Marks on the bones indicate they were deliberately cut with trepanation techniques. This confirmed that the tools were intended for use in surgery.

While the tools are unique for the region, a similar find was made in Paracas in 1929. The tools are made of different materials, however. The blades in the Paracas set were made with sharpened volcanic obsidian.

“It is the first discovery of this type here in Lambayeque and in the north of the country. It dates from the year 900 to 1050 after Christ, of Middle Sicán cultural affiliation, which speaks of the specialization and expertise that existed at this time. We are not only documenting elite cult figures linked to metallurgy but also specialists and surgical interventions”, [Sican National Museum Director Carlos Elera] highlighted.

A piece of bark from an unknown tree found in the bundle may have been used for medicinal purposes as an analgesic or anti-inflammatory infusion the same way white willow bark makes what is basically aspirin tea.

“This will be investigated to find out what species it belonged to and what use is currently given. We have to make a detailed typology of the surgical instruments to compare them with the Paracas instruments. There are some that coincide and some that don’t, but what is interesting is the case of Lambaye, where an object has the auction of the God of the Mask with Closed Eyes always present”, he mentioned.