An excavation in the waterfront Bjørvika neighborhood of Oslo has unearthed the remains of a long section of a wharf believed to have been built by a medieval king of Norway. More than 26 feet of the foundations of the pier have survived in excellent condition under the thick clay of the Oslofjord seabed.

An excavation in the waterfront Bjørvika neighborhood of Oslo has unearthed the remains of a long section of a wharf believed to have been built by a medieval king of Norway. More than 26 feet of the foundations of the pier have survived in excellent condition under the thick clay of the Oslofjord seabed.

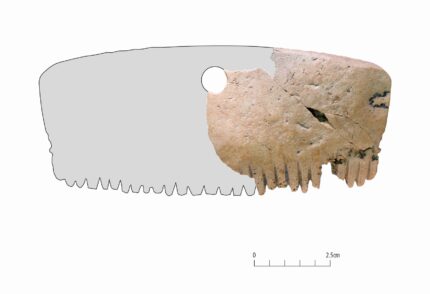

The wharf foundation was built by interlacing massive logs into bulwarks that were then embedded into the seabed. Impressions of barnacles and mussels on the logs indicate they were left exposed in the water. The structures built on top of the foundations over time pressed them deeper into the clay where they were preserved even when the surface structures were lost.

A small mystery is that inside the bulwark there are several layers of dung, food waste, fish bones and sodden peat.

“This is very mysterious,” says [NIKU archaeologist and project manager Håvard] Hegdal. “How has this come into what has been a closed construction? There has been a floor above us, and probably a building, and it shouldn’t be possible to throw food scraps and other things down here.”

“There was also a lot of dirt from a boat inside these layers. And it shouldn’t have come in here in any case. So ‘King’s wharf’ may have had a reasonably short lifespan, and that is quite strange.”

Slices will be taken from the bulwark logs so they can be dated dendrochronologically. Haakon V (r. 1299-1319) is the likeliest candidate for construction of the wharf. It was during his reign that Oslo surpassed Bergen to become capital of Norway, and it was Haakon who had the Akershus Fortress built to defend the city and as a royal residence. The foundations of the pier were found right outside the remains of the royal palace that preceded Akershus Fortress.

Slices will be taken from the bulwark logs so they can be dated dendrochronologically. Haakon V (r. 1299-1319) is the likeliest candidate for construction of the wharf. It was during his reign that Oslo surpassed Bergen to become capital of Norway, and it was Haakon who had the Akershus Fortress built to defend the city and as a royal residence. The foundations of the pier were found right outside the remains of the royal palace that preceded Akershus Fortress.

If the timbers date to after 1319, then it wasn’t a royal wharf after all because after Haakon’s death the property was given to the dean of St. Mary’s Church. A layer of blue clay covering the remains was deposited in a mudslide in the late 14th century so that’s the outside date boundary, but the wharf was built long before then.

The remains of the wharf have been scanned to create a 3D model.