The most ambitious digitization project I’ve ever heard of is halfway to its goal of putting every single publicly owned oil painting (plus tempera and acrylic) in the United Kingdom online. A joint effort of the Public Catalogue Foundation and the BBC, Your Paintings now has 104,000 artworks by the likes of Degas and Rubens uploaded to the website out of an estimated 200,000. It’s the first national online art museum ever attempted. Just to give you a sense of the scale, there are only 3,000 paintings in the immense National Gallery.

The most ambitious digitization project I’ve ever heard of is halfway to its goal of putting every single publicly owned oil painting (plus tempera and acrylic) in the United Kingdom online. A joint effort of the Public Catalogue Foundation and the BBC, Your Paintings now has 104,000 artworks by the likes of Degas and Rubens uploaded to the website out of an estimated 200,000. It’s the first national online art museum ever attempted. Just to give you a sense of the scale, there are only 3,000 paintings in the immense National Gallery.

You’d have to visit over 3,000 art galleries, museums, libraries, etc. to see the Your Paintings collection in person, and even that wouldn’t be enough. Some of the paintings are in private institutions like Bishop’s palaces and Oxford and Cambridge (they were deemed important national patrimony despite their technical private ownership) and aren’t on display. Even the ones in public museums are often in storage or being conserved. An estimated 80% of the 200,000 oil paintings in the national collection are not available for public viewing at any given time. Besides, even if you could access all of the paintings, it’s unlikely you’d get well-known actors and artists to take you on a guided tour of their favorite pieces and themes.

You can already search the website by artist, collection, location and thanks to the 5,000 members of the public (plus curators and experts) who have signed up to tag each painting with relevant subjects, soon you’ll be able to search the entire database by keyword as well. There are over a million tags already in the system. If you’d like to be a tagger too, sign up here.

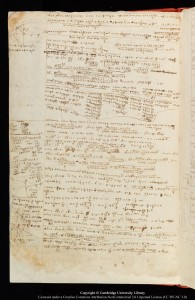

If your interests lie more on the history of science spectrum, Cambridge University Library has digitized and uploaded 4,000 pages of works by Sir Isaac Newton, including a fully annotated copy of the Principia Mathematica, drafts of his book on optics, his college notebooks and the “Waste Book,” a large volume filled with Newton’s notes and calculations, including some important work in the development of calculus, that he used when he had to leave Cambridge during the Great Plague of 1664.

Each page has been scanned individually in high resolution. You can zoom in on the smallest detail, or you can zoom out and read the transcription of the sometimes challenging handwriting. (Not all pages have transcriptions.) You can also download images of every page.

Each page has been scanned individually in high resolution. You can zoom in on the smallest detail, or you can zoom out and read the transcription of the sometimes challenging handwriting. (Not all pages have transcriptions.) You can also download images of every page.

The Cambridge Digital Library, in collaboration with the Newton Project at the University of Sussex, has been digitizing their Newton manuscripts since June 2010. They had to take their time with it because many of the works were in need of conservation before they could be scanned. These 4000 pages are just the beginning. Thousands more pages will be uploaded in the coming year. The ultimate goal is to have Cambridge’s full Newton collection online.

Once that’s done, they’ll move on to digitize their collection of works by Charles Darwin and the archive of the Board of Longitude.

What a festive post, in the spirit of Holiday Giving! It is interesting that the UK is the first nation to launch an online painting repository of this kind. Italy??? We should live so long!!!

With one salient exception, Italy’s immense cultural patrimony has the worst, I mean the worst, websites in the technologically advanced world. Have you see the Musei Vaticani site? And that mess is a recent upgrade! I can’t tell you how many times I’ve shaken my tiny fist at some atrocious contentless website that not only doesn’t do justice to the site/museum/church it describes, but actively makes it look bad.

The salient exception, of course, is the great star shining in the cybereast, a beacon for all wise webmasters to follow: the Medici Archive Project.

Someday, going to a museum will merely involve turning on your computer and going to its virtual location. That will happen eventually, thanks largely to the foresight of initiatives such as this–a necessary precursor to generate the content to facilitate that experience. This is a dominant goal and central strategy of the Smithsonian Institution as one more example.

Also collaborations with net technology companies like Google Art Project, which provides an additional value that visitors in person cannot experience: the extreme closeup zoom. That’s one aspect of the Your Paintings site that’s a little disappointing right now. Most of the pictures aren’t high resolution; some of them aren’t even modern. It’s just a baby, though. There’s plenty of room for it to grow. 🙂

“Access to images” (especially on the web) and “Access to original works of art and other objects” (by live visits to the host institutions) are two related but distinct needs. It is important that both be facilitated as much as possible–and those institutions that rise to the challenge of online access deserve our admiration and gratitude. HOWEVER, going to a museum will NEVER “merely involve turning on your computer and going to its virtual location”. And I doubt that the Smithsonian has quite that in mind–although they have been pioneers in on-line access.

I logged in and started tagging yesterday, it’s very addictive but I have to say I’m starting to give the abstract paintings a miss, there is very little one can say about monotone blocks or squiggles to help distinguish one painting from the next. 😮

😆 I know just what you mean. I’ve been doing what I usually do just for my own edification with abstract paintings: researching them thoroughly in the hope of finding an apt tag or two.

This is incredible. Since I started making Geocities pages back in the day, I knew that the internet would be the place where all of this knowledge locked away in libraries and hallways would be revealed. We started with animated skull .gifs, so really, we can only go up . . .

No kidding. 😉 Although, we can also go weirdly sideways, but that’s awesome in its own way.

I have intimate, direct knowledge of what the Smithsonian Institution intends to accomplish in the future. SI has numerous stated goals and strategies to this effect that are readily available to the public, if you look for them. The URL above provides one example of this initiative, which by the way, was developed well over a year ago. There is much more to come and SI is committed to providing access to people who cannot enjoy the the direct experience of visiting a museum. For many people, a virtual visit will be the ONLY opportunity they have because they cannot afford to see the real thing–so for them it will ALWAYS be the option of choice–and I applaud the SI for making this possible now and into the future.

True that. Screen real estate is also getting cheaper and cheaper, so what most people look at now on a 17″ monitor might soon be regularly seen on 60″ screen. It’s already fairly easily accomplished with an HDTV and an HDMI cable. What the Smithsonian and other institutions are working on now is already great for those of us who don’t have the opportunity to travel to see them in person, but they are also laying the groundwork for a future when a regular joe will get to examine something tiny in high magnification, or virtually manhandle something so delicate that in real life it can’t even be touched.

Liv; You are exactly right. I just spent 300+ hours this year working on a group project that enables researchers the world over to see in great detail thousands of invertegbrate zoology type specimens. The next challenge is to develop 360 degree rotations of selected specimens for various audiences–museum visitors, students and researchers. Digitized resources are coming faster than many people realize.

There are many advantages to the use of digitized images but also many dangers–especially when it comes to visual (especially stylistic) evidence in the fine arts. Works of art and archival documents are the objects with which I have had the most experience–and I can imagine that the use of zoological specimens involves different criteria. In recent years, it has become ridiculously easy (through the wonders of Photoshop) for people (scholars as well as art dealers)to cook the evidence. And I have seen this happen on more than a few occasions–manipulating comparative material to make paintings and drawings look alike or different in order to prove a point. When it comes to iconography or basic pictorial composition, nothing beats a quick run through a few hundred or thousand relevant images. But it is dangerously easy to lose touch with objects as physical objects, unless you have first-hand experience with original material–so that you can make the essential mental adjustments for size, media, condition, etc. A manuscript illumination and a wall fresco can look disconcertingly similar on a computer screen! Finally, there is the aesthetic issue–the fundamental difference in experience between seeing a real object and a digital image, for recreational museum goers and scholars alike… Oddly enough, scanned images of documents are often easier to read than the originals (especially with the technology that is now available for enlarging details, enhancing contrast, eliminating bleed-through)–except when they are not! Sometimes, the best method is to put the scanned image and the original document next to each other and work back and forth! It is obvious, I think, that a whole range of complex synergies is now emerging and we don’t know where much of this is going to take us. So, it is important to avoid simplistic reasoning. “Technology is the answer!” “What is the question?”

Ed; Your needs are evidently different from the vast majority of people who can benefit from increased access to knowledge through digital content. So, keep on working with your art objects and waxing eloquently over the nuances. Some people care about such subtleties. So if you’re that type of connoisseur, then go to the museum and ignore the stuff that is online.

However, actually going to the museum does not ensure that everything you see is what it is advertised to be and there are plenty of instances where fakes and forgeries have been discussed even in this blog. Just because digital content can be “Photoshopped” doesn’t mean that this type of material is inherently suspect. Nor does it mean that digital material poses some sort of danger to disconnect the unwitting from the world around them. It’s just a different medium serving a different purpose—and a different audience. To suggest that such reasoning is simplistic is disingenuous. To construe that digital content is an answer looking for a question is to miss the point. Perhaps you could expand your understanding of the advantages of digital technology by further exploring how can be applied as a tool to specifically enhance the quality of your own work.

Edward actually is something of a pioneer in digitization of historical material, Mr. Murphy. He founded one of the earliest, most ambitious projects out there: the digitization of the Medici Granduchal Archive, in my opinion hands down the greatest work done in Italy to digitize that country’s enormous cultural patrimony.

Mr. Murphy–Actually, I think that you and I agree on the principal point under discussion. We are both talking about different media serving different purposes (or in some cases, several different purposes at once.) And the range of technical options has been expanding rapidly–and with it, the range of public expectations and public needs. I have spent many years working in the area of database design and online delivery, collaborating with a variety of technical specialists and assessing feedback from a variety of users–always, however, in the area of humanities computing. That is probably why I am so interested in these particular issues and implications. Ed G.

Why do the Brits always have the awesome stuff? At least this way everyone has access. Very nice!

Once again, all hail “livius drusus” for making me aware of all these wonderful on-line archives. My health means traveling to these museums is not likely, but that doesn’t mean I can’t enjoy their bounty anyway! The world is full of wonder, and the interwebs is my window to everything amazing and beautiful; how can anyone with access ever be bored!

I think it’s great, to digitize these things. I must say, though, that I was never truly interested in art, until my first trip to the Guggenheim back in the early 2000s.

It’s awesome to be able to look at great masterpieces online, but alas, I never truly appreciated it.

When I got to the Guggenheim for the first time, the experience of seeing the ACTUAL brushstrokes, up-close, of people that are long-dead, and extremely famous, was awe-inspiring. I never realized just how much paint a lot of these paintings have used. There are some paintings that have such huge mounds of paint sticking out, that it looks as though you could easily stab someone in a hundred different places at one time by hitting them over the head with it.

😆 This is true. On the other hand, in some cases you can actually get a far better impression of an artwork by examining a digital reproduction. The Mona Lisa, for example, is behind so much protective plexiglass that you can’t get anywhere near it. Add the crowds and how tiny it is and you might as well be looking at it through a backwards telescope.

Never been to the Lourve (spelling?). But I can see your point for the really really famous pieces. However, I think most pieces world-wide are displayed in such a way, that the up close experience could beat the online experience. At least, I sure hope so.

Been to Europe on two occasions (mostly Italy) and have visited a couple of museums. I don;t remember those museums very well because, as a 12 year-old, I was bored out of my mind. I wanted to see the old buildings, not some old pictures.

I grew up in Italy, and I bitched and moaned about all the museums my parents dragged me to well into my teens. They knew what they were doing when they ignored me. Look at how I turned out!