A member of an informal group dedicated to researching local history in Ontario thinks he’s cracked the code found on the remains of a World War II carrier pigeon, the code that the Government Communications Headquarters (GCHQ), Britain’s code-breaking unit, declared virtually unbreakable just three weeks ago.

Gord Young, of Lakefield Heritage Research in Peterborough, Ontario, thought the GCHQ and Bletchley Park experts were overthinking the issue. He decided to use the World War I Royal Flying Corp aerial observers’ book he had inherited from his great-uncle to see if the pigeon’s message was more simple than anyone expected. Seventeen minutes later, he had a coherent deciphered message. To whit:

Gord Young, of Lakefield Heritage Research in Peterborough, Ontario, thought the GCHQ and Bletchley Park experts were overthinking the issue. He decided to use the World War I Royal Flying Corp aerial observers’ book he had inherited from his great-uncle to see if the pigeon’s message was more simple than anyone expected. Seventeen minutes later, he had a coherent deciphered message. To whit:

Artillery observer at ‘K’ Sector, Normandy. Requested headquarters supplement report. Panzer attack – blitz. West Artillery Observer Tracking Attack.

Lt Knows extra guns are here. Know where local dispatch station is. Determined where Jerry’s headquarters front posts. Right battery headquarters right here.

Found headquarters infantry right here. Final note, confirming, found Jerry’s whereabouts. Go over field notes. Counter measures against Panzers not working. Jerry’s right battery central headquarters here. Artillery observer at ‘K’ sector Normandy. Mortar, infantry attack panzers.

Hit Jerry’s Right or Reserve Battery Here. Already know electrical engineers headquarters. Troops, panzers, batteries, engineers, here. Final note known to headquarters.

That’s not the entire message. Gord was unable to decipher some parts of it which he thinks may be specialized World War II acronyms which his World War I code book obviously can’t cover. They could also be “fillers,” nonsense added deliberately to confuse the enemy in case the messages was interception.

As for why a World War II soldier would have been using a World War I code, Young speculates that the sender’s trainer was a World War I veteran, a “former Artillery observer-spotter.” He deduced this based on the “Serjeant” spelling of the sender’s rank, a holdover from WWI. I’ve read conflicting reports on the whole “Serjeant” issue, whether it denoted RAF over artillery or just some specialized artillery units or now this World War I trainer theory. I don’t have the expertise to weigh their plausibility.

GCHQ, who released a statement on November 22nd entitled “Pigeon takes secret message to the grave,” says it’s interested in examining Young’s work but remains insistent that they were right to give up after three weeks.

“We stand by our statement of 22 November 2012 that without access to the relevant codebooks and details of any additional encryption used, the message will remain impossible to decrypt,” he said.

“Similarly it is also impossible to verify any proposed solutions, but those put forward without reference to the original cryptographic material are unlikely to be correct.”

Somebody’s defensive. Not that Young couldn’t be completely wrong, of course, but it seems to me the odds are very slim that he’d have been able come up with something relevant and cogent if his code book was way off-base.

I’m not sure where they’re getting it, but several articles about the putative code-breaking also include new information about the sender, Sjt Stot. Apparently Sergeant William Stott was a paratrooper with the Lancashire Fusiliers. He was 27 years old when he (and some pigeons, apparently) parachuted behind enemy lines in Normandy on a mission to assess the strength of German forces. He was killed in action just weeks after the message was sent and is buried in a war cemetery in Normandy.

I’d rather buy that it’s the real deal. Seems silly that his deciphered message would be fake.

It seems unreasonable that 5 letter groups would yield what appears to be sensible plain text if the acronym code was not being used. Given how complex many WWII codes were I find it absolutely hilarious the modern GCHQ apparently made the same mistake Jerry did in 1944 and assumed it must be at a minimum a Playfair cipher.

Hats off for Sjt. Stott and all those of his ilk who used courage, Mark I eyeballs and carrier pigeons to make a difference. And hats off for Gord Young, and his excellent research.

Viewed charitably, this “solution” is improbable and at least unverifiable unless the details of the code book supposedly used were also published.

Viewed realistically, it’s complete drivel for several reasons:

a) Five letter code groups are used for two reasons: 1) It breaks up sentence structure which can tell you a lot about the message contained, 2) To make encryption less error prone. The second point suggests that an encryption algorithm was used.

b) Simple mistake by our expert. The message doesn’t contain “PABLIZ”, one of the code groups “decyphered” by out expert. It says “PABUZ.”

c) The letter frequencies look wrong for it to be a simple set of acronyms or plain English.

d) The explanation given simply doesn’t make sense. There are holes in it you could drive a bus through! Why would an artillery observer be able to make up his own code/cipher when these were standardised? The “Serjeant” spelling link to his trainer is tenuous and unproven.

e) The supposedly decrypted message contains no useful or verifiable information of any kind.

Sorry chaps. Pile of cack.

AC

“Found headquarters infantry right here. Final note, confirming, found Jerry’s whereabouts. Go over field notes.”

Wasted words to say the same thing. Military would not have trained such bloated wording. :skull:

Mike,

I was unable to find any references to Playfair in conjunction with this story but I can say with some certainty that no cryptographer would mistake the message for being a Playfair.

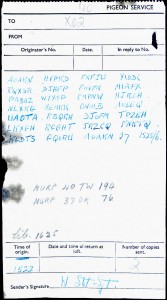

The Playfair is a digraphic cipher (two plaintext letters in combination produce two ciphertext letters). That means any message in Playfair would have to contain an even number of letters and the message is composed of 27 five letter code groups for a total of 135 letters.

In addition, when composing a message to be enciphered in Playfair the sender must separate doubled letters (ex. the double TT in leTTers) when the first of the doubled letters is at an odd numbered position in the message. This is usually done by inserting a letter (typically X) between the pair as the Playfair system does not allow for enciphering doubled letters. In addition, the enciphered message cannot contain doubled letters in odd/even positions, as this would render that letter pair indecipherable.

This message contains three sets of odd/even pairs, the YY in the 10th group, the KK in the 14th group and the GG in the 22nd group.

Some additional observations…

The 1st code group (AOAKN) is repeated at the end of the message. This might be some sort of indicator of the specific code being used or the enciphering or super-enciphering method used. In addition, it strongly suggests that if the message is in code as opposed to cipher then the code words are 5 letter groups. For radio transmissions, 5 letter groups was the norm, but this was sent by pigeon and if the code consisted of 4 letter groups then it most likely would have been written that way. In any event, the 135 letters are only divisible by 3 and 5 and if a 3 letter code was employed it would make the AOAKN repetition problematical.

If the sender was a Sergeant Stott I find it rather strange that he would have signed the message and dropped the final T from his name. Perhaps he was under duress, but that he had time to abbreviate his rank (Sjt) would indicate that he wasn’t in a panic to get the message off. That he was not under duress would be supported by the fact that the time of origin was given as 1522 (and also apparently as 1525 at the end of the message) but the identification codes for the birds as well as the writing just above the time of origin box appear to be in a slightly different colored pencil and indicate that the messages were actually sent nearly an hour later (at 1625).

Until Mr. Young produces the code book which he used to provide the decipherment for public inspection I would not venture a guess on the plausibility of his decipherment other than to say the decipherment does not appear to be consistent with what one might expect in a tactical message as it is very general in nature.

My own suggestion for a possible decipherment would be to attempt a solution employing the M-94 with the AOAKN serving as some form of M-94 cylinder placement key with the remaining 125 letters being the actual message. M-94s were used during WW II and even after they had been replaced by the M-209 Converter. An M-94 is about the size of a roll of half dollars and was very suitable for tactical messages and didn’t require a code book.

Absolute rot which has been blindly repeated by press and media across the globe. WW2 messages were routinely chopped into five-letter blocks to disguise word-lengths. Word-blocks were written and read left-to-right, not in columns. A call sign at the start (in this case AOAKN) was repeated at the end so the recipient could be sure they had the whole message. This looks exactly like every other British coded military message from the war.

OR an artillery observer in Normandy used a Royal Flying Corps code from more than 20 years earlier to send a long, rambling message as a series of acronyms to someone back at headquarters who also used the same WW1 RFC code to decipher it – even though it looks exactly like a regular WW2 coded message.

If you examine the ‘solution’ in detail, it is clear that this Canadian has missed some letters out, added some others in, and changed some others (notably reading U as W) to make it fit. Absolute rot.

He Hasn’t cracked the cipher!

I agree that he hasn’t cracked the cipher, but until someone does present a consistent and plausible translation this messsage is fair game for anyone with a notion to figure it out.