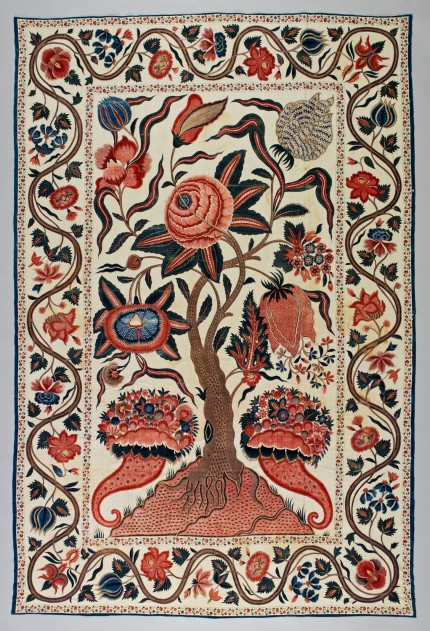

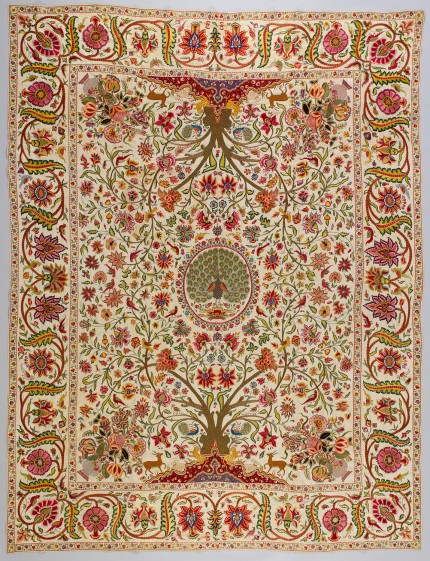

The Peabody Essex Museum (PEM) in Salem, Massachusetts has acquired a rare collection of 18th century Indian textiles that are in such spectacular condition that you’d be forgiven for thinking they were made yesterday. Made in the early 1700s for export to the Netherlands, the cotton chintz textiles include jackets, men’s dressing gowns (banyans), women’s dressing gowns (wentkes), children’s caps and bed coverlets known as palampores both hand-painted and embroidered.

There are about 170 textiles in the collection, all assembled by historian Alida Eecen-van Setten between 1927 and 1969. Some she bought from antiques dealers, others she scavenged from the trash, documenting every acquisition in her “chintz book.” She shared her collection with fabric designers who used the patterns in their creations and with other historians, keeping the chintz book current as new research suggested different dates. After her death, her granddaughter Lieke Veldman-Planten took charge of the textiles and the book. The collection is named after both women: the Veldman-Eecen Collection.

The textiles are decorated with vibrantly colored floral motifs that began as naturalistic garden scenes commissioned by Babur, the first Mughal emperor of India, in the 16th century but had become stylized botanicals by the reign of Shah Jahan, builder of the Taj Mahal, in the 17th century. They were hand-painted and fixed using mordant and resist dying techniques that ensured the bright colors of natural dyes like red madder and blue indigo held fast without fading. Nothing in Europe could compare to the intensity and durability of Indian colors.

Portuguese traders began exporting Indian textiles in the 1500s, but it was the Dutch East India Company (VOC) that began large scale exports in the 17th century. It started out as a branch of the spice trade since Indian cloth was used as currency in Indonesia and the Spice Islands. Merchants would buy textiles with European bullion, trade some of them for spices and then sell both the cloth and the spices in Europe. By the late 17th century, England, France and the Dutch Republic each imported more than a million pieces of chintz a year.

Many textile words in English are imports from India. Bandanas were Bengal handkerchiefs sold as neck cloths to sailors and laborers; chintz comes from the word “chitra” meaning “spotted.” Calico, khaki, gingham, dungarees, pyjamas, and my personal favorite, seersucker, are all Indian words for textiles and garments that became ubiquitous in Europe during the heyday of the textile trade.

The explosion of popularity of imported textiles sent local cotton producers into a tailspin. France prohibited the import of chintz in 1686; England followed suit in 1720, prohibiting not just its import but also its use in furniture, bedding and clothing. Demand remained high, however, and as inevitably happens with prohibitions of pretty much any kind, making the importation of Indian chintz illegal just created a burgeoning black market.

Ultimately it was duplication and industrialization starting in the late 18th century that killed the Indian export textile trade. Machine-printing and synthetic dyes made possible the speedy manufacture of large quantities of cheap fabrics. Expensive imports couldn’t compete.

Alida Eecen-van Setten’s interest in collecting and documenting these textiles was unusual at the time. Formerly fashionable consumer goods weren’t popular subjects for historians, and keeping 200-year-old organic fabrics from decaying is not an easy thing. There are very few 18th century chintzes available on the antiquities market (or in dumpsters) today. Her taste, persistence and dedication saved these exquisite textiles for a time when they could be appreciated as the museum pieces they are. She collected in such depth that the collection today is pretty much ideal for museum display. There are 15 chintz baby caps, for example, so the museum will be able to rotate them in and out of public view to keep them all in optimal condition.

In 2015, the Peabody Essex Museum will partner with no less illustrious an institution than the Rijksmuseum for an exhibition about the Dutch East India Company’s vast and influential trade in Asian imports. The Veldman-Eecen Collection will feature prominently in the Asia in Amsterdam exhibition that will run in Amsterdam from October 16th, 2015 until January 17th, 2016, after which it will travel to the Peabody Essex.

Salem’s Peabody Essex – a dynamic and rapidly expanding museum – is the perfect home for this stunning collection. I remember back when it was still “The China Trade Museum”. The partnership with the Rijksmuseum is certainly the right thing at the right time.

Thank you for posting! Can’t wait to see the exhibit!

I am seriously coveting those jackets. So beautiful! Thank you, Livius, for brightening a sleep deprived day.

Oh wow, those are gorgeous.

Fabulous! Such delicious photos. I kept trying to peer closely, but not enough resolution. Now on my list of must-go-to-see-soons. There are some benefits to living in Vermont, and proximity to museums like this is one of them. Will take magnifying glass for study.

I am in love with that blue and white long gown. OMG!

Gorgeous indeed.

Hurrah for Alida! :boogie:

So wanting to see this exhibit. Might not wait for 2016.

Dear Sirs,

Please find my new paper- historiography by objectives

http://www.scribd.com/doc/261605162/Sujay-Historiography-by-Objectives-Final-Final-Final

Sujay Rao Mandavilli

Thank You for Posting such a Beautiful collection,I never use to write in any blogs..But this Fabulous textiles made me to write about them…I am also collector and Dealer but i have never seen such a Fabulous Textiles..Waiting to see this exhibition..