Napoleon was by all reports a loving father to his only child, his son with Marie Louise of Austria Napoleon François Charles Joseph Bonaparte, styled at birth the King of Rome, a modified version of the traditional title, King of the Romans, granted to all heirs apparent of the Holy Roman Empire. The last time Napoleon saw his little King of Rome was in the middle of the night of January 24th, 1814, at the palace of Saint Cloud. He said his goodbyes to his wife and son before heading to the north of France to fight the encroaching Allied forces.

Napoleon was by all reports a loving father to his only child, his son with Marie Louise of Austria Napoleon François Charles Joseph Bonaparte, styled at birth the King of Rome, a modified version of the traditional title, King of the Romans, granted to all heirs apparent of the Holy Roman Empire. The last time Napoleon saw his little King of Rome was in the middle of the night of January 24th, 1814, at the palace of Saint Cloud. He said his goodbyes to his wife and son before heading to the north of France to fight the encroaching Allied forces.

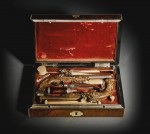

If the Roi de Rome received a goodbye present from his father, it may well have been a present his father commissioned for his son’s upcoming third birthday in March. Napoleon ordered a pair of bespoke dueling pistols from gunsmith to the French monarchs Jean Le Page. Made of blue steel with walnut and ebony stocks and inlaid with gold, the guns were custom-made to fit a young boy’s hands. Engraved on the lock of the pistols is the fateful production date, Janv. (January) 1814.

If the Roi de Rome received a goodbye present from his father, it may well have been a present his father commissioned for his son’s upcoming third birthday in March. Napoleon ordered a pair of bespoke dueling pistols from gunsmith to the French monarchs Jean Le Page. Made of blue steel with walnut and ebony stocks and inlaid with gold, the guns were custom-made to fit a young boy’s hands. Engraved on the lock of the pistols is the fateful production date, Janv. (January) 1814.

Whether the Roi de Rome received his last present from his father is not known. The pistols remained behind as Napoleon’s empire fell completely apart in a matter of weeks and he was compelled to abdicate under pressure from the Allies, first in favor of his son, and then in favor of nobody. Technically the King of Rome’s pistols were now the property of the newly restored Bourbon King of France Louis XVIII, but the new king wasn’t all that keen to keep a tight grip on the previous throne-holder’s stuff. People who wanted to buy a piece of Napoleon, and there were many such people, could do so easily on the streets of Paris. One of those people was William Bullock.

Whether the Roi de Rome received his last present from his father is not known. The pistols remained behind as Napoleon’s empire fell completely apart in a matter of weeks and he was compelled to abdicate under pressure from the Allies, first in favor of his son, and then in favor of nobody. Technically the King of Rome’s pistols were now the property of the newly restored Bourbon King of France Louis XVIII, but the new king wasn’t all that keen to keep a tight grip on the previous throne-holder’s stuff. People who wanted to buy a piece of Napoleon, and there were many such people, could do so easily on the streets of Paris. One of those people was William Bullock.

Bullock began as a jeweler and silversmith by profession, living and working in Liverpool. Conveniently located in a port city that was a trade capital of the empire, Bullock was able to acquire specimens and artifacts from sailors who had traveled all over the world. He opened his first museum of curiosities in Liverpool in 1795. He was a dedicated naturalist, an elected member of several exclusive natural history societies, an interest reflected in his collection and which gave its display an educational purpose as well. Bullock was the first in England to arrange exhibits in habitat groups, displaying specimens in some semblance of their natural surroundings.

Bullock began as a jeweler and silversmith by profession, living and working in Liverpool. Conveniently located in a port city that was a trade capital of the empire, Bullock was able to acquire specimens and artifacts from sailors who had traveled all over the world. He opened his first museum of curiosities in Liverpool in 1795. He was a dedicated naturalist, an elected member of several exclusive natural history societies, an interest reflected in his collection and which gave its display an educational purpose as well. Bullock was the first in England to arrange exhibits in habitat groups, displaying specimens in some semblance of their natural surroundings.

In 1809 he moved to London and opened the Liverpool Museum at 22 Piccadilly. It was an immediate hit, welcoming more than 22,000 visitors its first month, and 80,000 in its first six. In April of 1811, one of the visitors was the 35-year-old Jane Austen who wrote to her sister Cassandra that she and her cousin Mary Cooke “after disposing of her father and mother, went to the Liverpool Museum and the British Gallery, and I had some amusement at each, though my preference for men and women always inclines me to attend more to the company than the sight.”

By then Bullock had already begun construction of a new building to house his museum at the south end of Piccadilly (today street numbers 170-173). Designed by architect Peter Frederick Robinson who was inspired by the engravings in Description de l’Egypte, the building was the first building in England constructed entirely in Egyptian style, interior and exterior, since Egyptomania had swept Europe after Napoleon’s 1798 campaign in Egypt. The new building had a vast grand hall modeled after the Temple of Dendera that allowed exhibitions of large scale art and artifacts.

By then Bullock had already begun construction of a new building to house his museum at the south end of Piccadilly (today street numbers 170-173). Designed by architect Peter Frederick Robinson who was inspired by the engravings in Description de l’Egypte, the building was the first building in England constructed entirely in Egyptian style, interior and exterior, since Egyptomania had swept Europe after Napoleon’s 1798 campaign in Egypt. The new building had a vast grand hall modeled after the Temple of Dendera that allowed exhibitions of large scale art and artifacts.

In A Companion to Mr. Bullock’s London Museum and Pantherion, a brochure with descriptions of many of the thousands of specimens in the museum, makes it clear that when it opened in 1812, Bullock’s museum on Piccadilly was almost entirely focused on natural history. Animals dominate, with more than 100 pages dedicated to specimens from stuffed giraffes to porpoise jaws. Artifacts were mainly garments, jewelry and use objects from the South Seas, Africa, North and South America, although there is a 16-page chapter dedicated to the museum’s armoury most of which had been acquired from the estate of Dr. Richard Greene’s, a surgeon who a few decades earlier had exhibited his own museum of curiosities in two rooms of his Lichfield home.

The Egyptian Hall’s capacity was put to test in 1816 when Bullock exhibited Napoleonic artifacts while Waterloo was still fresh in the public mind. The centerpiece of the show was Napoleon’s bullet-proof travelling carriage which he had used as a home away from home during his campaigns all over Europe and which had been captured by the Prussian army after the Battle of Waterloo. In October of 1815, General Blücher arranged for the carriage to be presented to the Prince Regent who, terminally in need of money, turned around and sold it to William Bullock for around £2,500. That price won bought the carriage, its contents — Napoleon’s personal belongings including his folding camp bed and his travelling kit with 100 solid gold pieces and a million francs in diamonds stashed inside — and two of the deposed emperor’s horses.

The Egyptian Hall’s capacity was put to test in 1816 when Bullock exhibited Napoleonic artifacts while Waterloo was still fresh in the public mind. The centerpiece of the show was Napoleon’s bullet-proof travelling carriage which he had used as a home away from home during his campaigns all over Europe and which had been captured by the Prussian army after the Battle of Waterloo. In October of 1815, General Blücher arranged for the carriage to be presented to the Prince Regent who, terminally in need of money, turned around and sold it to William Bullock for around £2,500. That price won bought the carriage, its contents — Napoleon’s personal belongings including his folding camp bed and his travelling kit with 100 solid gold pieces and a million francs in diamonds stashed inside — and two of the deposed emperor’s horses.

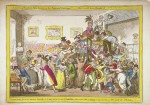

The Napoleon exhibition ran from January to August 1816 and drew massive crowds of up to 10,000 visitors a day. They crowded the Egyptian Hall, climbing all over Napoleon’s carriage and pawing through his stuff. In the final tally, about 220,000 visitors saw the Napoleon show in London and more than 800,000 people saw the carriage and associated exhibition on its traveling tour of England, Scotland and Ireland. From his initial outlay of £2,500 for the carriage, Bullock made £35,000.

The Napoleon exhibition ran from January to August 1816 and drew massive crowds of up to 10,000 visitors a day. They crowded the Egyptian Hall, climbing all over Napoleon’s carriage and pawing through his stuff. In the final tally, about 220,000 visitors saw the Napoleon show in London and more than 800,000 people saw the carriage and associated exhibition on its traveling tour of England, Scotland and Ireland. From his initial outlay of £2,500 for the carriage, Bullock made £35,000.

With visions of even sugarier plums dancing in his head, Bullock decided to open the Museum Napoleon to make even more money from the public fascination with the fallen foe. To add to the exhibition, he went to Paris in January of 1816 and purchased a myriad Napoleonic knick-knacks from the Emperor’s servants, friends and his imperial residences of Malmaison and St. Cloud. It was probably at one of the palaces where Bullock acquired the Roi de Rome’s dueling pistols.

With visions of even sugarier plums dancing in his head, Bullock decided to open the Museum Napoleon to make even more money from the public fascination with the fallen foe. To add to the exhibition, he went to Paris in January of 1816 and purchased a myriad Napoleonic knick-knacks from the Emperor’s servants, friends and his imperial residences of Malmaison and St. Cloud. It was probably at one of the palaces where Bullock acquired the Roi de Rome’s dueling pistols.

The fever for all things Napoleon couldn’t and didn’t last. By 1818, Bullock was actively looking for buyers, universities and museums, to acquire his entire collection. When the University of Edinburgh and the British Museum turned him down, he took matters into his own hands. In 1819, Bullock sold his collection, by then composed of more than 32,000 objects, in an auction that lasted 26 days and netted him £9,974. Napoleon’s carriage was sold to a coachmaker for £168. In 1843 it was bought by Madame Tussaud’s where it remained on display until it was destroyed in a fire that devastated the waxworks in 1925.

The Roi de Rome Pistols were bought at the great 1819 auction by someone identified in the documents only as “Levery.” They likely passed through several hands before they made their next appearance in the historical record in the Paris Exposition Universelle of 1900 where they were put on display by gunmakers James Purdey & Sons. The pistols soon thereafter found a home with Cora, Countess of Strafford, the rich widow of soap magnate Samuel Colgate and model for the character of Cora Crawley, Countess of Grantham, in Downton Abbey. In the 40s the pistols were acquired by William Keith Neal for his renown collection of arms and his descendants have decided to sell.

The Roi de Rome Pistols were bought at the great 1819 auction by someone identified in the documents only as “Levery.” They likely passed through several hands before they made their next appearance in the historical record in the Paris Exposition Universelle of 1900 where they were put on display by gunmakers James Purdey & Sons. The pistols soon thereafter found a home with Cora, Countess of Strafford, the rich widow of soap magnate Samuel Colgate and model for the character of Cora Crawley, Countess of Grantham, in Downton Abbey. In the 40s the pistols were acquired by William Keith Neal for his renown collection of arms and his descendants have decided to sell.

The toddler king’s wee pistols will be put on the auction block at Sotheby’s Treasures sale on July 8th. The presale estimate is £800,000-1,200,000 ($1,251,844 – 1,877,856).

“Napoleon’s carriage … was bought by Madame Tussaud’s where it remained on display until it was destroyed in a fire ..”: sic transit.

Where can I buy a print of Napoleon seated with his son? to place it on a mark?