On June 30th, 1859, French acrobat Charles Blondin was the first person to walk across Niagara Falls on a tightrope. Born Jean François Gravelet in 1824, Blondin began his career as performer of acrobatic stunts when he was five years old. Orphaned at age nine, he continued in his chosen career, constantly challenging himself to develop new stunts until he grew from child prodigy into one of the greatest funambulist in France. In 1851 he was invited to join the Ravel Troupe, a sort of acrobatic-ballet-pantomime Menudo with a revolving door of members drawn from some of the most prominent French and Italian performing families, on their tour of the United States.

On June 30th, 1859, French acrobat Charles Blondin was the first person to walk across Niagara Falls on a tightrope. Born Jean François Gravelet in 1824, Blondin began his career as performer of acrobatic stunts when he was five years old. Orphaned at age nine, he continued in his chosen career, constantly challenging himself to develop new stunts until he grew from child prodigy into one of the greatest funambulist in France. In 1851 he was invited to join the Ravel Troupe, a sort of acrobatic-ballet-pantomime Menudo with a revolving door of members drawn from some of the most prominent French and Italian performing families, on their tour of the United States.

In 1855 the Ravel Troupe was booked by café owner, caterer and theatrical impresario William Niblo to play Niblo’s Garden theater on Broadway in New York City. Always popular, the Ravel Troupe got rave reviews and had their booking extended, ultimately performing more than 300 shows from 1857 to 1859. Blondin, however, didn’t stay put. He formed a splinter troupe (this happened all the time with the Ravel groups; it wasn’t rancorous; everyone got more work that way) with one of Ravel’s lead acrobats, Julian Martinetti, and they toured the country as the Martinetti-Blondin troupe. Blondin was reviewed glowingly in the press as “the bold and fearless Mons. Blondin.” In a six degrees of separation coincidence, at Crisp’s Gaiety in New Orleans in November 1857, the Martinetti-Blondin troupe shared billing with “the popular young native tragedian, Mr. Edwin Booth.”

In 1855 the Ravel Troupe was booked by café owner, caterer and theatrical impresario William Niblo to play Niblo’s Garden theater on Broadway in New York City. Always popular, the Ravel Troupe got rave reviews and had their booking extended, ultimately performing more than 300 shows from 1857 to 1859. Blondin, however, didn’t stay put. He formed a splinter troupe (this happened all the time with the Ravel groups; it wasn’t rancorous; everyone got more work that way) with one of Ravel’s lead acrobats, Julian Martinetti, and they toured the country as the Martinetti-Blondin troupe. Blondin was reviewed glowingly in the press as “the bold and fearless Mons. Blondin.” In a six degrees of separation coincidence, at Crisp’s Gaiety in New Orleans in November 1857, the Martinetti-Blondin troupe shared billing with “the popular young native tragedian, Mr. Edwin Booth.”

After almost eight years on the road with the Ravels, Blondin’s troupe disbanded in late 1858 in Cincinnati. According to his 1862 biography by George Linnaeus Banks, the night of the troupe’s farewell dinner Blondin dreamed that he crossed “the boiling flood” of Niagara Falls “on a silken line as delicate as a thread of gossamer” to the wild acclaim of throngs of spectators. Never one to shy away from a seemingly insane proposition, Blondin went to Niagara to see if he could make his dream come true. He realized it wouldn’t work in the winter because the ice formed by the mist would make the line slippery and brittle.

After almost eight years on the road with the Ravels, Blondin’s troupe disbanded in late 1858 in Cincinnati. According to his 1862 biography by George Linnaeus Banks, the night of the troupe’s farewell dinner Blondin dreamed that he crossed “the boiling flood” of Niagara Falls “on a silken line as delicate as a thread of gossamer” to the wild acclaim of throngs of spectators. Never one to shy away from a seemingly insane proposition, Blondin went to Niagara to see if he could make his dream come true. He realized it wouldn’t work in the winter because the ice formed by the mist would make the line slippery and brittle.

Undeterred, Blondin returned to Niagara in spring of 1859 and began to plan his crossing. He and his manager Harry Colcord struggled to get the permits to string the rope. Blondin wanted it strung across Horseshoe Falls where all the drama is, but landowners protested that the mist would soak the hemp rope and make it too slick. In the end Blondin strung his cable from the trunk of an oak tree in White’s Pleasure Grounds on the American side across Niagara Gorge to a rock in front of the Clifton House on the Canadian side, near to where the Rainbow Bridge is today. The rope was 1,100 feet long and just 3.25 inches in diameter. It was poised 160 feet above the Niagara River with a slight sag in the middle 50 feet where it was impossible to attach the guy lines that kept the rest of the cable from swaying too vigorously. It took Blondin and Colcord almost five months to get the cable and lines strung.

Undeterred, Blondin returned to Niagara in spring of 1859 and began to plan his crossing. He and his manager Harry Colcord struggled to get the permits to string the rope. Blondin wanted it strung across Horseshoe Falls where all the drama is, but landowners protested that the mist would soak the hemp rope and make it too slick. In the end Blondin strung his cable from the trunk of an oak tree in White’s Pleasure Grounds on the American side across Niagara Gorge to a rock in front of the Clifton House on the Canadian side, near to where the Rainbow Bridge is today. The rope was 1,100 feet long and just 3.25 inches in diameter. It was poised 160 feet above the Niagara River with a slight sag in the middle 50 feet where it was impossible to attach the guy lines that kept the rest of the cable from swaying too vigorously. It took Blondin and Colcord almost five months to get the cable and lines strung.

At 5:00 PM on June 30th, Charles Blondin gripped his 26-feet-long ash balancing pole and walked across the tightrope from the United States to Canada. He sat down in the middle, looked around like he hadn’t a care in the world, then stood back up and kept walking. He stopped again to lay down on his back, did a back somersault and then traipsed with a gait described by one spectator as akin to that of a “barnyard cock” to the other side. The whole crossing had taken him five minutes.

At 5:00 PM on June 30th, Charles Blondin gripped his 26-feet-long ash balancing pole and walked across the tightrope from the United States to Canada. He sat down in the middle, looked around like he hadn’t a care in the world, then stood back up and kept walking. He stopped again to lay down on his back, did a back somersault and then traipsed with a gait described by one spectator as akin to that of a “barnyard cock” to the other side. The whole crossing had taken him five minutes.

Twenty minutes later, Blondin started the return trip. This time he had a Daguerreotype apparatus strapped to his back which he duly deployed 200 feet into his crossing. He tied his balancing pole to the rope, set up the camera and took a picture of the crowd waiting for him on the American side. Then he strapped the camera back onto his back and finished the crossing. That one took 23 minutes.

As soon as he was done, still basking in the acclaim of the stupefied audience of 25,000, Blondin announced he’d attempt another Niagara tightrope walk on the Fourth of July. He accomplished that one too, without a balancing pole, doing flips and tricks and the return crossing wearing a bag over his head. Blondin would make many more crossings, each with different and increasingly daring stunts. He walked it backwards, did flips all the way across, crossed at night, pushed a wheelbarrow across the rope and strapped a stove to his back so he could make an omelette midway through the crossing which he didn’t even eat himself. He lowered it on a rope to the passengers on the Maid of the Mist. He carried Henry Colcord on his back several times.

As soon as he was done, still basking in the acclaim of the stupefied audience of 25,000, Blondin announced he’d attempt another Niagara tightrope walk on the Fourth of July. He accomplished that one too, without a balancing pole, doing flips and tricks and the return crossing wearing a bag over his head. Blondin would make many more crossings, each with different and increasingly daring stunts. He walked it backwards, did flips all the way across, crossed at night, pushed a wheelbarrow across the rope and strapped a stove to his back so he could make an omelette midway through the crossing which he didn’t even eat himself. He lowered it on a rope to the passengers on the Maid of the Mist. He carried Henry Colcord on his back several times.

His Niagara Falls exploits made him internationally famous and quite wealthy. His name became synonymous with walking a tightrope, a metaphor that became painfully apt for a divided country soon after his first crossing. Abraham Lincoln was repeatedly depicted in editorial cartoons as Blondin. In 1860, when Lincoln was running for president, Vanity Fair put “Mr. Abraham Blondin De Lave Lincoln” in pantaloons and tights crossing a breaking rail with a black baby in a carpetbag. Harper’s Weekly cartoon depicted him carrying a slave — the Republican party’s position on slavery — across a tightrope with the Constitution as his balancing pole.

His Niagara Falls exploits made him internationally famous and quite wealthy. His name became synonymous with walking a tightrope, a metaphor that became painfully apt for a divided country soon after his first crossing. Abraham Lincoln was repeatedly depicted in editorial cartoons as Blondin. In 1860, when Lincoln was running for president, Vanity Fair put “Mr. Abraham Blondin De Lave Lincoln” in pantaloons and tights crossing a breaking rail with a black baby in a carpetbag. Harper’s Weekly cartoon depicted him carrying a slave — the Republican party’s position on slavery — across a tightrope with the Constitution as his balancing pole.

Lincoln embraced the comparison himself, utilizing it in response to his critics during the 1864 election.

Gentlemen, suppose all the property you were worth was in gold, and you had put it in the hands of Blondin to carry across the Niagara River on a rope, would you shake the cable, or keep shouting out to him — “Blondin, stand up a little straighter–Blondin, stoop a little more–go a little faster–lean a little more to the north–lean a little more to the south?” No, you would hold your breath as well as your tongue, and keep your hands off until he was safe over. The Government are carrying an immense weight. Untold treasures are in their hands. They are doing the very best they can. Don’t badger them. Keep silence, and we’ll get you safe across.

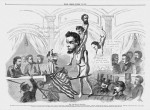

Frank Leslie’s Budget of Fun of September 1st, 1864, published a cartoon of the scene, with Lincoln carrying two men on his back this time (Secretary of the Navy Gideon Welles on Lincoln’s shoulders and War Secretary Edwin Stanton on Welles’s shoulders), pushing a wheelbarrow filled with money, Columbia and the American flag while all around him people talk smack.

Frank Leslie’s Budget of Fun of September 1st, 1864, published a cartoon of the scene, with Lincoln carrying two men on his back this time (Secretary of the Navy Gideon Welles on Lincoln’s shoulders and War Secretary Edwin Stanton on Welles’s shoulders), pushing a wheelbarrow filled with money, Columbia and the American flag while all around him people talk smack.

As for Blondin, he would go on to perform all over the world, drawing amazed and horrified crowds everywhere he went. He retired briefly in the late 1870s, but went back on the stage in 1880 and continued to walk, cycle, push lions in wheelbarrows over the tightrope until his final performance in 1896. He died just a few months later in February of 1897 at the age of 72 from diabetes.

“while all around him people talk smack”: what does that mean?

Thank you so much for publishing the paired stereo photographs. (Too frequently people publish only one of a pair.) I love seeing the 3D effect in these venerable images.

To “talk smack” is to “trash talk”, something like how boxers talk about their opponents before a big fight. The people are hurling insults at Lincoln and saying how he will lose the next election I presume.

NIAGRA FALLS! Slowly, I turned, step by step…

Thank you.

Does the Daguerreotype Blondin took while in mid-crossing still exist?

I don’t know. I searched far and wide for it when I was researching this story and could only find references to the act, not to a developed photograph.

Oddly, I just finished reading a book by a modern Irish author who used the expression “talking smack”. I sussed from the context that it must mean something like trash talk or dissing people. I

wonder if it might be Irish slang, or something derived from the Irish language. Or if, as so many colloquial terms, borrowed it from somewhere else?