A pair of dismembered mummy legs found in Queen Nefertari’s tomb (QV66) in the Valley of the Queens likely belonged to the queen herself, new research indicates.

A pair of dismembered mummy legs found in Queen Nefertari’s tomb (QV66) in the Valley of the Queens likely belonged to the queen herself, new research indicates.

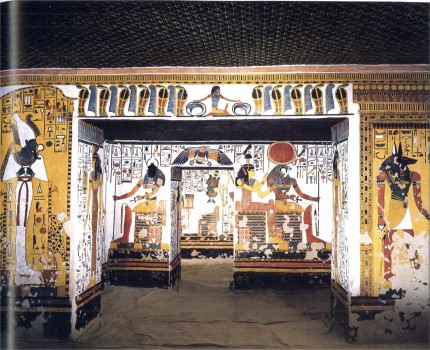

Nefertari was the second and favorite Great Royal Wife of Pharaoh Ramesses II (r. 1279-1213 B.C.). Ramesses the Great so loved Nefertari that he built a temple to her next to his at Abu Simbel. Her colossal figures are the same size as his, a symbol of the immense respect and status he granted her. His love for her is literally painted on the walls of her tomb. Poetry he wrote praising and mourning her (“My love is unique — no one can rival her, for she is the most beautiful woman alive. Just by passing, she has stolen away my heart.”) shares space with scenes from the Book of the Dead, Nefertari in he daily life and the afterlife.

Nefertari was the second and favorite Great Royal Wife of Pharaoh Ramesses II (r. 1279-1213 B.C.). Ramesses the Great so loved Nefertari that he built a temple to her next to his at Abu Simbel. Her colossal figures are the same size as his, a symbol of the immense respect and status he granted her. His love for her is literally painted on the walls of her tomb. Poetry he wrote praising and mourning her (“My love is unique — no one can rival her, for she is the most beautiful woman alive. Just by passing, she has stolen away my heart.”) shares space with scenes from the Book of the Dead, Nefertari in he daily life and the afterlife.

Queen Nefertari’s tomb was discovered in 1904 by preeminent Italian Egyptologist Ernesto Schiaparelli. (If that name rings a bell, it’s because he was a member of an illustrious family of brilliant people including his cousin astronomer Giovanni Schiaparelli who first observed the channels on Mars, and Giovanni’s niece Elsa Schiaparelli, the dazzlingly innovative fashion designer who invented much of what we take for granted in the industry today.) One of the largest tombs in the Valley of the Queens, its elaborately painted walls survive in beautiful condition earning it the moniker of the Sistine Chapel of Ancient Egypt, but the contents of the tomb had been looted and trashed in antiquity. All that was left inside were some small objects (broken pottery, 34 wood shabtis, coffer lids, a faience pommel knob bearing King Ay’s throne name “Kheper-Kheperu-Ra”), fragment of her pink granite sarcophagus, broken furniture, a pair of very fine sandals woven from vegetal fiber and two mummified human legs broken in pieces.

Queen Nefertari’s tomb was discovered in 1904 by preeminent Italian Egyptologist Ernesto Schiaparelli. (If that name rings a bell, it’s because he was a member of an illustrious family of brilliant people including his cousin astronomer Giovanni Schiaparelli who first observed the channels on Mars, and Giovanni’s niece Elsa Schiaparelli, the dazzlingly innovative fashion designer who invented much of what we take for granted in the industry today.) One of the largest tombs in the Valley of the Queens, its elaborately painted walls survive in beautiful condition earning it the moniker of the Sistine Chapel of Ancient Egypt, but the contents of the tomb had been looted and trashed in antiquity. All that was left inside were some small objects (broken pottery, 34 wood shabtis, coffer lids, a faience pommel knob bearing King Ay’s throne name “Kheper-Kheperu-Ra”), fragment of her pink granite sarcophagus, broken furniture, a pair of very fine sandals woven from vegetal fiber and two mummified human legs broken in pieces.

The remains are in three parts: one long leg piece composed of a patella and part of a femur and tibia, a medium piece composed of part of a tibia, and a short piece of a femur. Because Schiaparelli was the director of the Museo Egizio in Turin from 1894 until his death in 1928, the finds he’d made over 20 years of excavations in Egypt were added to the museum’s collection, among them the contents of QV66, including the mummy legs. Today the Museo Egizio houses more than 300,000 objects making it the second largest Egyptian museum in the world. The Egyptian Museum in Cairo is number one, of course.

The remains are in three parts: one long leg piece composed of a patella and part of a femur and tibia, a medium piece composed of part of a tibia, and a short piece of a femur. Because Schiaparelli was the director of the Museo Egizio in Turin from 1894 until his death in 1928, the finds he’d made over 20 years of excavations in Egypt were added to the museum’s collection, among them the contents of QV66, including the mummy legs. Today the Museo Egizio houses more than 300,000 objects making it the second largest Egyptian museum in the world. The Egyptian Museum in Cairo is number one, of course.

Because they were found in Nefertari’s tomb, which is thoroughly identified as such from inscriptions on the walls and surviving artifacts, the legs were believed to be the remains of the queen, but they’ve never been scientifically studied until now. A multidisciplinary team subjected the legs to radiocarbon dating, X-rays, osteological analysis, DNA testing, anthropological comparison, chemical analysis and historical research.

Because they were found in Nefertari’s tomb, which is thoroughly identified as such from inscriptions on the walls and surviving artifacts, the legs were believed to be the remains of the queen, but they’ve never been scientifically studied until now. A multidisciplinary team subjected the legs to radiocarbon dating, X-rays, osteological analysis, DNA testing, anthropological comparison, chemical analysis and historical research.

Anthropometric reconstruction and assessment of the size of the knees revealed they belonged to a woman whose stature ranged between 165 cm (5 foot 5 inches) and 168 cm (5 foot 6 inches).

The body height was also independently estimated by professor Maciej Henneberg at the University of Adelaide, Australia, who obtained the same results — a stature of about 165 cm.

“Data about women from the New Kingdom and 3rd Intermediate Period show she was probably taller than 84 percent of the women of her time,” Rühli said.

Analysis of the materials used for embalming showed they were consistent with Ramesside mummification traditions, while X-rays of the left knee pointed to possible traces of arteriosclerosis, suggesting the legs belonged to an elderly person.

“The accumulated evidence could point to an individual between 40 and 60 years old,” Rühli and colleagues wrote.

That matches the Egyptological research into Nefertari’s age and approximate time of death around the 25th year of her husband’s long, long reign. The size of the sandals found in the tomb also match the stature and dimensions of the legs. Their quality suggests royal use as well.

That matches the Egyptological research into Nefertari’s age and approximate time of death around the 25th year of her husband’s long, long reign. The size of the sandals found in the tomb also match the stature and dimensions of the legs. Their quality suggests royal use as well.

Unfortunately, no useable DNA could be extracted — the samples were too contaminated — so there will be no genetic information forthcoming. Radiocarbon dating results indicated the remains were around two centuries older than Queen Nefertari going by the current chronology.

“A discrepancy between radiocarbon dating and Egyptian chronology models has long been debated. Indeed, some question on the chronological model of the New Kingdom may now arise,” Habicht said.

“For the future, we strongly suggest radiocarbon dating of other royal and non-royal remains of the Ramesside era, in order to validate or disprove the chronology,” he added.

You can read the full study published in the journal PLOS ONE.

No DNA from inside the bones or mummified flesh? How could those areas be contaminated? Something else is going on here I’d say, or else the data they got was inconvenient for some reason?

Sounds like this could stand the test of time. Anyone? Great article interesting research.

“Patient Turin 34, Nefertari, Egyptian Mummy, born 01.01.1910” 😆 – When her husband was going to be examined and restored, and therefore was flown to Paris back in 1974, he was issued an Egyptian passport that listed his occupation as “King (deceased)”.

I remember having been invited to a massive Turkish wedding with hundreds of other attendees. Later that evening, I found myself encircled by roughly 20 young Turkish ladies in full attire, dancing in frenzy all around me, and virtually none of them was taller than 5 foot 6 inches, that is including their very elaborate hairstyles – The Wolf and the Twenty little girls

Ok, Ramesses would have had 2000 of them, at least.

And I always thought Joe Tex wrote “Skinny Legs And All” as a shot at Diana Ross? Who knew?

Very interesting article!

Rob–It could also have to do with the age of the bones too. The older the material, the harder it is to get DNA. If the bones were broken and discarded in a heap, bugs or remains from embalming materials could have gotten in contact with the bones too, which would compromise them. They only had two leg bones, and maybe not even the complete legs. In order to do a DNA test, you also need enough intact bits of DNA to run a test. Just because you have some bone doesn’t mean there’ll be enough DNA altogether to do a test.