A painted wooden crucifix by Michelangelo Buonarrotti has returned to its original home, the Basilica of Santa Maria del Santo Spirito in Florence, after a fresh restoration and a year on the road. Carved by the artist when he was 18 or so, it’s one of his earliest extant works. Not the earliest, though, because Michelangelo’s artistic gifts were evident from a very young age.

A painted wooden crucifix by Michelangelo Buonarrotti has returned to its original home, the Basilica of Santa Maria del Santo Spirito in Florence, after a fresh restoration and a year on the road. Carved by the artist when he was 18 or so, it’s one of his earliest extant works. Not the earliest, though, because Michelangelo’s artistic gifts were evident from a very young age.

Michelangelo was apprenticed to Domenico Ghirlandaio, then at the peak of his popularity and productivity, in 1488. It’s a testament to Michelangelo’s indisputably immense talent (and his irascible father’s insistence) that even though he was just 13 years old, his apprenticeship contract guaranteed him a salary, six florins for the first year, eight for the second, 10 for the third. This kind of deal was very much against custom for such a young, unproven apprentice. Michelangelo was special, though, and Ghirlandaio knew it.

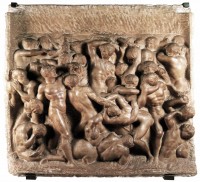

The lad didn’t end up spending three years in Ghirlandaio’s workshop as per contract anyway. In 1489, Lorenzo de’ Medici asked Ghirlandaio to send his two best students to an academy for sculptors and painters Lorenzo had founded in his palace gardens where he also maintained an extensive collection of Roman antiquities. This was a seminal period for the teenaged Michelangelo. Lorenzo took a personal interest in him, inviting him to live in the palace and exposing him to the greatest Humanist thinkers, artists and poets of the era assembled at the Medici court. He carved his first two sculptures at Lorenzo’s academy, the marble bas reliefs the Madonna of the Stairs and the Battle of the Centaurs, the latter showcasing how strongly influenced Michelangelo was by classical design already. For the rest of his life he would consider himself first and foremost a sculptor no matter how famous and in demand he became for his frescoes and paintings.

The lad didn’t end up spending three years in Ghirlandaio’s workshop as per contract anyway. In 1489, Lorenzo de’ Medici asked Ghirlandaio to send his two best students to an academy for sculptors and painters Lorenzo had founded in his palace gardens where he also maintained an extensive collection of Roman antiquities. This was a seminal period for the teenaged Michelangelo. Lorenzo took a personal interest in him, inviting him to live in the palace and exposing him to the greatest Humanist thinkers, artists and poets of the era assembled at the Medici court. He carved his first two sculptures at Lorenzo’s academy, the marble bas reliefs the Madonna of the Stairs and the Battle of the Centaurs, the latter showcasing how strongly influenced Michelangelo was by classical design already. For the rest of his life he would consider himself first and foremost a sculptor no matter how famous and in demand he became for his frescoes and paintings.

The death of Lorenzo de’ Medici on April 8th, 1492, put an abrupt end to Michelangelo’s formative idyll. He moved back in with his father, but he continued to study on his own. The Augustinian prior of the convent of Santo Spirito allowed the artist rooms to live with them from the spring of 1493 until the fall of 1494 so he could do anatomical studies of cadavers in the associated hospital of Santo Spirito. Lorenzo’s son Piero de’ Medici, called the Unfortunate, who was a big fan of Michelangelo, gave him permission to dissect and examine the hospital’s corpses, a rare opportunity for a young artist, and one he did not squander.

He carved the polychrome wooden crucifix to thank the prior for giving him lodgings and an invaluable understanding of the human body. When medical professionals examined the carving a few years ago, they determined it was an accurate and realistic reproduction of a dead youth about 14 years old. It seems Michelangelo, then just a few years older than the deceased boy who served as his unwitting model, gave Santo Spirito the very fruits of the anatomical studies it had made possible.

He carved the polychrome wooden crucifix to thank the prior for giving him lodgings and an invaluable understanding of the human body. When medical professionals examined the carving a few years ago, they determined it was an accurate and realistic reproduction of a dead youth about 14 years old. It seems Michelangelo, then just a few years older than the deceased boy who served as his unwitting model, gave Santo Spirito the very fruits of the anatomical studies it had made possible.

The sculpture hung above the high altar of Santo Spirito until the early 17th century when the altar was replaced with a more elaborate one. Michelangelo’s simple design was no longer deemed appropriate for the new setting and it was moved. After the French occupation in the late 18th century and the dissolution of the monasteries, the crucifix was considered lost. In fact, it never left Santo Spirito. It was rediscovered in 1962 by German art historian Margrit Lisner during her cataloguing of Tuscan crucifixes. It was hanging in a corridor at the convent and had been so thickly overpainted that not just its color was altered, but its form as well. With the original features dreadfully obscured in this condition, Lisner’s identification of it as the Michelangelo work was very much in doubt.

The sculpture hung above the high altar of Santo Spirito until the early 17th century when the altar was replaced with a more elaborate one. Michelangelo’s simple design was no longer deemed appropriate for the new setting and it was moved. After the French occupation in the late 18th century and the dissolution of the monasteries, the crucifix was considered lost. In fact, it never left Santo Spirito. It was rediscovered in 1962 by German art historian Margrit Lisner during her cataloguing of Tuscan crucifixes. It was hanging in a corridor at the convent and had been so thickly overpainted that not just its color was altered, but its form as well. With the original features dreadfully obscured in this condition, Lisner’s identification of it as the Michelangelo work was very much in doubt.

Nonetheless, it was cleaned and restored and put on display in the Casa Buonarrotti Museum, where it remained until December 2000 when it was returned to the basilica of Santo Spirito. While still not universally accepted, the attribution question was largely settled the next year when Umberto Baldini, director of the cultural division of Italy’s National Research Council, declared the carving the work of Michelangelo after a thorough artistic and forensic examination.

Nonetheless, it was cleaned and restored and put on display in the Casa Buonarrotti Museum, where it remained until December 2000 when it was returned to the basilica of Santo Spirito. While still not universally accepted, the attribution question was largely settled the next year when Umberto Baldini, director of the cultural division of Italy’s National Research Council, declared the carving the work of Michelangelo after a thorough artistic and forensic examination.

Now it has returned to its original stomping grounds, but in a new location. When the church reinstalled it in 2000, the crucifix was affixed to a side wall and could only be seen from the front. Today it hangs above the church’s old sacristy so people can walk beneath and around it and can view it from all sides.

This is the only fully naked representation of Christ (bar baby Christ) that I have ever seen.

O/T but entertaining.

https://www.futilitycloset.com/2017/04/04/when-in-rome-5/

Yes, he is indeed depicted naked here, by the way with a remarkably small –almost ‘classically’ designed– [you know what], but with more realistic proportions, it could all too easily break off. Therefore, the reasons for that were certainly practical ones.

Of interest is also the ‘titulus crucis’, i.e. the ‘INRI’, ‘ΙΝΒΙ’ or (tsarist) ‘ІНЦІ’ inscription in Latin, Greek and what might have been Hebrew or Aramaic.

Here, the Latin and Greek is also written from right to left, similar to that plank –the ‘original’ one of course, what else?– stored in the in the church ‘Santa Croce in Gerusalemme’, not in Florence but Rome.

There is a fully naked Christ in polychrome wood in the Hospital de Tavera in Toledo, which has been speculatively attributed to El Greco since it appears to be based on the figure of Christ in the artist’s Resurrection painting of 1603-07 in the Prado. I illustrated it on page 82 of my book The Body in Sculpture (The Body in Three Dimensions in the Abrams US imprint). It also has a vestigial penis (let’s not mince words), but originally had a removable loin cloth to protect his diminutive modesty, which Michelangelo appears not to have provided for his. I’m still sceptical about the Michelangelo attribution in the Santo Spirito figure.

Fascinating to read more about the story of this crucifix. Although I have a MA in history of art, I know most of Michelangelo’s work, including this one, through repeated readings of The Agony and the Ecstasy as a teen and I always enjoy learning more about and seeing his earlier works that don’t get as much attention as David or the Sistine ceiling.

I’m wonder to whom I can send photos of a corpus I acquired, for assistance.

Description:

Vintage European carved wooden corpus of Christ. Previously painted multiple times. Remnants of paint on corpus. Predominantly “bone white” color. Red pigment around wounds in hands, feet and side. Hints of green in some areas.

Head slightly tilted to the left; face with closed eyes; open asymmetrical “V”- arms forming a scalene traingle (no equal sides, see below); rib cage well defined with pronounced muscular fascia; perzonium tied at the hip; vertical legs, right foot superimposed on the left foot, overlapping; depicted in expired posture.

No crown of thorns. Beard not bifurcated (not bi-parted).

[I believe that the perzonium and the hand-forged “eyelet” on the backside of the corpus are critical to identifying the time and original of production. I recognize that the eyelet hanger could have been affixed at a later time than when it was sculpted.]

Dimensions:

Right hand to feet = 91.5 cm (36 inches)

Left hand to feet = 86.3 cm (34 inches)

Right hand to left hand = 58.4 cm (23 inches)

Top of head to top of perzonium = 35.6 cm (14 inches)

Top of perzonium to tip of feet = 45.7 cm (18 inches)

Chest width = 11.4 cm (4.5 inches)

Top of head to tip of beard = 15.25 cm (6 inches)

Top of head to tip of feet = 81.3 cm (32 inches)

Country or Origin: Oral history from private owner/collector uncertain but believes his recollection is that it is 1600s, a German or Flemish “Low Country” sculpture.

BTW: Romans most commonly crucified men naked. In the earliest representations, Jesus usually carries a colobium—a form of tunic. —more rarely a subligaculum (A form of underware worn by both men and women in ancient Rome, the subligaculum was one of the most basic garments. It was very similar to the perizoma employed on in nearly corpa. In ancient Roman culture the main function of the subligaculum was to cover the genitals. (Think: Roman gladiators and common workmen). During the Middle Ages, there was debate because the Gospel according to John says that the Roman soldiers share the tunic of Christ. From the 8th century, artists gradually abandoned colobium in favor of the perzonium, which was imposed around the 11th century, creating different styles of drapery.

See:

http://www.fashionencyclopedia.com/fashion_costume_culture/The-Ancient-World-Rome/Subligaculum.html