After the digitization of the World War I memorabilia, we went to the room next door where the Bruce Museum had its small but impeccable collection of World War I propaganda posters on display. About 3 dozen posters were on display, almost all of them in flawless condition with color lithography still vibrant. They were arranged in thematically-related groups, which illustrated how many angles artists used to approach the same subjects.

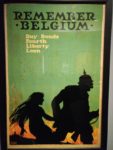

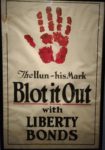

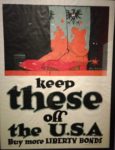

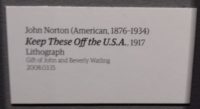

Perhaps the most compelling grouping from my perspective were the violent, disturbing ones that demonized the enemy as blood-thirsty barbarians. Some are a shock to the system, and would have doubtless been even more so in 1917-1918.

Another group of posters was dedicated to the mobilization of women as Red Cross volunteers, nurses and in the ubiquitous sale of bonds, stamps and other products devised to help finance the war. One poster stood out for me the most with its saturated color and detailed design:

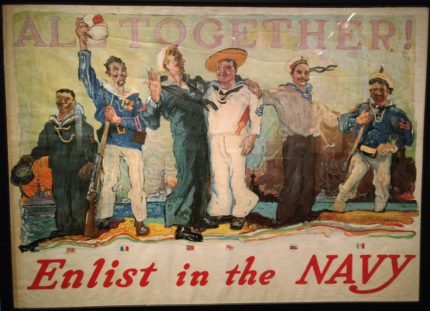

Meanwhile, over in the section where recruitment posters reached out to American men to volunteer for the services if at all possible, I was struck by a rather happy piece with a Village People sort of vibe. It calls for men to join the US Navy by showing them in cheerful comraderie with sailors from around the world.

Posters were not the only things on display in the exhibition. There were some artifacts and two multimedia stations playing propaganda films on a loop. The first was an extraordinary piece of artwork by cartoonist and animation pioneer Winsor McCay. His most famous animated movie, Gertie the Dinosaur, released in 1914, was the first moving picture to have a dinosaur in it and while it wasn’t the first animated feature ever made, it stands out for its artistry and theme and has been studied and copied extensively.

In 1918, McCay created a masterpiece of animated innovation by way of propaganda: The Sinking of the Lusitania, as 12-minute animated recreation of the torpedoing of the RMS Lusitania. The tragedy was not filmed or photographed, so McCay relied on detailed descriptions from the Hearst Corporation’s Berlin correspondent August F. Beach to create his short film. It took him just shy of two years to finish the incredibly huge amount of drawing required to make this serious, dramatic subject come alive for 12 minutes. It was the longest animated feature ever made up until that point. The picture was not a box office hit, but it did fulfill its political purpose of making the sinking of the Lusitania a rallying cry for Americans, 123 of whose countrymen died on that ship.

The second film is lighter fare, starring a characteristically sweet, insouciant Mary Pickford learning how to rein in her profligacy so she can “do her bit” and buy a Liberty Bond. It’s a propaganda film, complete with her appeal straight to the audience in the end, but it also ties in with other propaganda media covered by the Bruce’s exhibition. There’s a “Hun” poster that shames her out of buying an ice cream sundae, and the title of the short is 100% American, a common motif in the recruiting and bond drive posters.

That is an impressive Lusitania sinking animation,attempting to describe what was a relatively novel form of warfare.

I have that Joan of Arc poster on a postcard, stuck to a bookcase. 🙂 And now I have the Village People “In the Navy” song stuck in my head, thanks a lot.

The National World War I Museum in Kansas City has quite a large poster collection available on line. Also, I believe that a fair number or reproduction WW1 posters are available.

For those who didn’t notice the little flags or who might be unsure of WW1 era banners the Allied sailors, left to right, are Japanese, French, American, British, Russian, and Italian. Note that the British flag is the Royal Navy jack, not the more commonly known Union Flag.

The poster cries out for a good caption contest. The British Jack Tar seems to be saying to the American, “Dude, you’re in my personal space. Boundaries, Man!”

Winsor McCay! I know (of) him! My favorite bit about him is: ‘The great “Looney Tunes” animator Chuck Jones wrote, “The two most important people in animation are Winsor McCay and Walt Disney, and I’m not sure which should go first.’ (Quoted from this article: https://www.cincinnati.com/story/news/2014/03/19/enquirer-artist-influenced-walt-disney/6608049/.)

Disney himself acknowledged that he was heavily influenced by McCay. Comic books also owe McCay for his pioneering use of panels and speech bubbles and playing with the layout thereof.