A fingerprint believed to have been left by Leonardo da Vinci has been found on one of his drawings in the UK’s Royal Collections. It was discovered by Alan Donnithorne, formerly the head paper conservator of the Royal Collections, who found the thumbprint on a red ink anatomical drawing. Fingerprints have been found on other works by Leonardo da Vinci, but this is the most likely one to have been left by the artist himself on one of the drawings in the Royal Collections.

A fingerprint believed to have been left by Leonardo da Vinci has been found on one of his drawings in the UK’s Royal Collections. It was discovered by Alan Donnithorne, formerly the head paper conservator of the Royal Collections, who found the thumbprint on a red ink anatomical drawing. Fingerprints have been found on other works by Leonardo da Vinci, but this is the most likely one to have been left by the artist himself on one of the drawings in the Royal Collections.

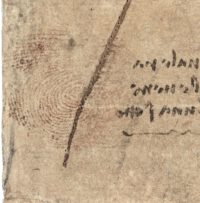

The drawing, The Cardiovascular System and Principal Organs of a Woman, was made around 1509-1510.  Donnithorne found the thumbprint on the left side of the sheet near the subject’s arm. The mark was left in the same dark red ink as Leonardo used to make the drawing. There is also a smudged print left by his left index finger on the back of the sheet.

Donnithorne found the thumbprint on the left side of the sheet near the subject’s arm. The mark was left in the same dark red ink as Leonardo used to make the drawing. There is also a smudged print left by his left index finger on the back of the sheet.

The UK is going all-out to commemorate the 500th anniversary of Leonardo da Vinci’s death on May 2nd of this year. It is taking the utmost advantage of the Queen Elizabeth II’s 550 works by the master, the largest single collection of Leonardos in the world. Remarkably, they’ve been together as a group since Leonardo died  half a millennium ago and have been in the Royal Collection since the 17th century. To mark the anniversary, there will be 12 simultaneous exhibitions of Leonardo drawings across the UK from February 1st through May 6th. Leonardo da Vinci: A Life in Drawing features 12 different drawings on display at each of the 12 museums in Southampton, Bristol, Cardiff, Birmingham, Derby, Liverpool, Sheffield, Manchester, Leeds, Sunderland, Belfast and Glasgow. The 144 drawings cover a wide range of interests pursued by the polymath: painting, sculpture, architecture, music, anatomy, engineering, cartography, geology and botany.

half a millennium ago and have been in the Royal Collection since the 17th century. To mark the anniversary, there will be 12 simultaneous exhibitions of Leonardo drawings across the UK from February 1st through May 6th. Leonardo da Vinci: A Life in Drawing features 12 different drawings on display at each of the 12 museums in Southampton, Bristol, Cardiff, Birmingham, Derby, Liverpool, Sheffield, Manchester, Leeds, Sunderland, Belfast and Glasgow. The 144 drawings cover a wide range of interests pursued by the polymath: painting, sculpture, architecture, music, anatomy, engineering, cartography, geology and botany.

The anatomical drawing and its thumbprint will go on display Friday at the National Museum Cardiff. After that, all 144 drawings will join up with a few dozen more of Leonardo’s works from the Royal Collections to go on display at The Queen’s Gallery at Buckingham Palace from May 24th until October 13th. This will be the largest exhibition of Leonardo da Vinci works in 65 years. The exhibition will travel to Scotland next where it will be exhibited at the Queen’s Gallery in the Palace of Holyroodhouse, the Queen’s official residence in Edinburgh, from November 22nd through March 15th, 2020. That will be the largest collection of Leonardo’s works ever shown in Scotland.

The anatomical drawing and its thumbprint will go on display Friday at the National Museum Cardiff. After that, all 144 drawings will join up with a few dozen more of Leonardo’s works from the Royal Collections to go on display at The Queen’s Gallery at Buckingham Palace from May 24th until October 13th. This will be the largest exhibition of Leonardo da Vinci works in 65 years. The exhibition will travel to Scotland next where it will be exhibited at the Queen’s Gallery in the Palace of Holyroodhouse, the Queen’s official residence in Edinburgh, from November 22nd through March 15th, 2020. That will be the largest collection of Leonardo’s works ever shown in Scotland.

In conjunction with the exhibitions, Alan Donnithorne has published a new scientific study of 80 of the Leonardo works in the Royal Collections. Leonardo da Vinci: A Closer Look reexamines those works in the light of the latest analytical technologies, including microscopy, ultraviolet imaging, infrared reflectography and X-ray fluorescence (XRF).

In conjunction with the exhibitions, Alan Donnithorne has published a new scientific study of 80 of the Leonardo works in the Royal Collections. Leonardo da Vinci: A Closer Look reexamines those works in the light of the latest analytical technologies, including microscopy, ultraviolet imaging, infrared reflectography and X-ray fluorescence (XRF).

One by one, Leonardo’s processes of creation are revealed, from his choice of paper and the composition of the specialist grounds used for his drawings, to his first touches in chalk, ink or metalpoint, and on to the finished compositions.

Many of these features are of course invisible to the naked eye, and have been so for centuries, ever since Leonardo took his pen from the paper. Infrared images reveal underdrawings unseen for 500 years, published here for the first time. Ultraviolet photography brings back to life now-vanished metalpoint sketches; while spectrographic analysis allows us to explore the origin and precise chemistry of Leonardo’s papers and grounds.

I really like those cats. In 1525, Dürer’s ‘Etliche underricht, zu befestigung der Stett, Schloß vndFlecken’ was printed >° °<

In the fingerprint closeup picture, you can see that the anatomical drawing has been pricked for transfer via pouncing. I wonder what Leonardo had in mind there?

I see pounce markings also, and over all the drawing following the muscles of the subject.

Maybe not Leonardo: Take into account that the hard-disks and filesystems that they were running on 500 years ago, were in fact much softer than ours. Also, they did not have those fancy online dictionaries and ‘dot-matrix printers’ were unheard of.

What they did have, contrastingly, were printers that were about to be invented, or at least more widely used, matrices, and of course needle-shaped dot pins. In addition, roughly estimated, more than 25 cadavers were spared, and there was much less odour.

:hattip:

————–

Cf. ‘De humani corporis fabrica libri septem’ (“On the fabric of the human body in seven [printed!] books”) from 1543, just a few years later than 1517. Of course, Vesalius/ Van Wesel cut his own cadavers (possibly after he had seen the measly copies of Leonardo’s works).

Maybe the anatomical drawing is the product of a pounced guide. In many places the drawing does not conform to the pouncing guides and shows numerous corrections. If it was being used to produce addition drawings I would have thought the pouncing holes would more carefully follow the lines of the drawing. Maybe Leonardo intended to produce a series of drawings of the same view as further organs were removed or exposed and this is just one.

…in which case, and if he did it himself, he would have invented the first ‘flip-book video’ –backwards, an empty cadaver being filled up with organs :boogie:

Yes, I would not completely rule out that this had been the idea. However, in this case, red-handed real medics might have indeed expected some form of Spanish Inquisition, and -I dare say- probably not without reason.

His margin notes appear to have been written backwards. Michaelangelo used sketches that were pounced when creating frescoes.