The copper alloy disc discovered in a shipwreck off the coast of Oman in 2014 has been independently verified by the Guinness Book of World Records as the world’s earliest known marine astrolabe. The disc was found in the debris field of the Esmeralda, one of the ships in the fleet Vasco da Gama took on his second voyage to India that sank in 1503. It had a hole in the middle and two raised decorations (a Portuguese royal coat of arms and the esfera armilar, King Manuel I’s personal emblem), but no unambiguous evidence of its function could be seen with the naked eye. In 2016, laser scans by Professor Mark Williams at WMG, University of Warwick, found lines etched along the edge of the upper right quadrant exactly five degrees apart, markers used by sailors to calculate their latitude. Those findings have now been confirmed by the Guinness Book researchers.

The copper alloy disc discovered in a shipwreck off the coast of Oman in 2014 has been independently verified by the Guinness Book of World Records as the world’s earliest known marine astrolabe. The disc was found in the debris field of the Esmeralda, one of the ships in the fleet Vasco da Gama took on his second voyage to India that sank in 1503. It had a hole in the middle and two raised decorations (a Portuguese royal coat of arms and the esfera armilar, King Manuel I’s personal emblem), but no unambiguous evidence of its function could be seen with the naked eye. In 2016, laser scans by Professor Mark Williams at WMG, University of Warwick, found lines etched along the edge of the upper right quadrant exactly five degrees apart, markers used by sailors to calculate their latitude. Those findings have now been confirmed by the Guinness Book researchers.

The exact date of the astrolabe’s manufacture could not be determined, but it had to have been made after 1495 when Manuel became King of Portugal and before 1502 when the ship departed Lisbon. Before this discovery, the oldest known astrolabe was found on a Portuguese shipwreck that sank off the coast of Namibia in 1533. The Esmeralda‘s bell dating to 1498 has also been confirmed as the oldest known ship’s bell, beating the previous record-holder the venerable Mary Rose, the Tudor flagship that sank in the Solent in 1545.

Oceanographer David Mearns of Blue Water Recoveries who led the diving team that discovered the wreck, University of Warwick researchers Mark Williams and Jason Warnett have published their findings on the astrolabe in the International Journal of Nautical Archaeology. It’s a great paper for layperson and scholar alike. It lays out the archaeological record of marine astrolabes, how rare they are overall and how almost none of them were excavated archaeologically which makes determining their provenance and background extremely challenging. Only ten were known in 1957 when the first astrolabe register was created by David Waters, curator of navigation and astronomy at the National Maritime Museum at Greenwich. As of publication, there are 105 astrolabes and four alidades (sights used on astrolabes) on the current list, which you can see a cool (but alas too small) picture of on page two of the paper. The Sodré astrolabe (named after Vicente Sodré who commanded the Esmeralda) is number 108.

Oceanographer David Mearns of Blue Water Recoveries who led the diving team that discovered the wreck, University of Warwick researchers Mark Williams and Jason Warnett have published their findings on the astrolabe in the International Journal of Nautical Archaeology. It’s a great paper for layperson and scholar alike. It lays out the archaeological record of marine astrolabes, how rare they are overall and how almost none of them were excavated archaeologically which makes determining their provenance and background extremely challenging. Only ten were known in 1957 when the first astrolabe register was created by David Waters, curator of navigation and astronomy at the National Maritime Museum at Greenwich. As of publication, there are 105 astrolabes and four alidades (sights used on astrolabes) on the current list, which you can see a cool (but alas too small) picture of on page two of the paper. The Sodré astrolabe (named after Vicente Sodré who commanded the Esmeralda) is number 108.

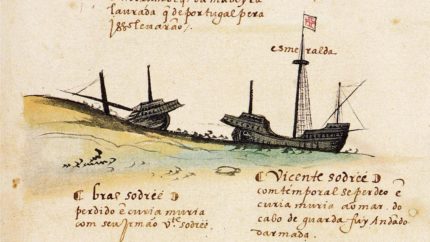

It also explains the whole story of how and why the Sodré brothers and their ships wound up in pieces off the coast of an Oman island and covers the excavation in which more than 2,800 objects were recovered, an incredible wealth of archaeological material that lends invaluable insight into Portuguese navigation in the Age of Discovery.

The paper goes into the astrolabe’s discovery and the results of years of study, but it also explains its significance in the larger context of the invention and earliest use of astrolabes.

What can be made of the observation that the Sodré astrolabe was only marked at 5-degree intervals and not with the 1-degree gradations seen in all other mariner’s astrolabes? Is it possible that at the time it was created the Portuguese, or at least the maker of this particular specimen, had not refined or standardized the design of their instruments to allow measuring altitude to the precision of 1-degree? Cline (1990: 130) claims that prior to the development of the heavy, open-wheel types, the early navigators were unable to take measurements within four to five degrees even on a ship that was not rolling. This might explain the absence of individual degree marks in the Sodré astrolabe if 5-degree divisions were deemed to be adequate by the navigators, presuming they could always estimate the position of the alidade between scale marks. Considering the general corroded state of the undecorated side and perimeter of the Sodré astrolabe, it is equally possible, however, that the individual gradations have been eroded away and that the faint traces of the 5-degree gradations were preserved because of their position further from the perimeter or possibly because the maker had scored them to a greater depth. […]

The astrolabe is unique in the archaeological record in a number of ways. It is the only known solid disc (type 0) mariner’s astrolabe with a verifiable provenance and age. This suggests it might be a transitional instrument in the development of mariner’s astrolabes.[…]

The Sodré astrolabe is also unique in that, of the 104-known instruments, it is the sole specimen decorated with a national symbol: the royal coat of arms of Portugal. Together with Manuel’s esfera armilar, these decorations dominate one side of the Sodré astrolabe. Their conspicuous placement, in relief, ensures that they stand out and would appear to mark the astrolabe as an object of the state. This is significant in light of Manuel’s use of royal symbolism to project his power at the precise time Portuguese ships were discovering new lands and his country was on the cusp of building the world’s first global empire.

Seriously, this is a page-turner, one of the most interesting, content-rich and comprehensible research papers I’ve read in a long time.

So much history and findings and the Portuguese government dont want to participate in anything.

Seems he’s ashamed with his history.

Thanks for teh sharing

Well, Nuno, I am not sure whether the Portuguese government does want to participate, or whether the work is being done essentially by the finders.