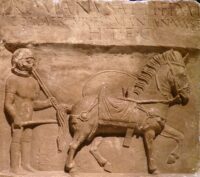

There are no Roman cavalry saddles surviving intact today. Depictions of them can be found on statues and monuments — grand reliefs like that cavalry battle on the Mausoleum of the Julii in Saint-Rémy-de-Provence (the two in southern France where Vincent van Gogh painted The Starry Night during his stay in the local asylum) as well as modest gravestones like that of Lucius Romanus, a Roman cavalryman of Illyrian origin who died while serving in what is now Cologne — so we know what they looked like.

There are no Roman cavalry saddles surviving intact today. Depictions of them can be found on statues and monuments — grand reliefs like that cavalry battle on the Mausoleum of the Julii in Saint-Rémy-de-Provence (the two in southern France where Vincent van Gogh painted The Starry Night during his stay in the local asylum) as well as modest gravestones like that of Lucius Romanus, a Roman cavalryman of Illyrian origin who died while serving in what is now Cologne — so we know what they looked like.

The iconography shows that Roman saddles consisted of a padded seat with four horns, two in front projecting to the sides over the rider’s thighs, and two straight ones behind the rider supporting the buttocks. The horns served to distribute the weight of the rider away from the horse’s spine to its flanks in an era before stirrups. Because archaeological remains of saddles have so far been limited to metal horn plates and fragments of leather from the cover, the construction framework of the Roman cavalry saddle is still up for debate.

Roman military historian Peter Connolly pioneered research into the construction of the saddle, publishing papers on the subject in the 1980s and 90s and creating dozens of experimental models. Based on contemporary depictions and his analysis of stress patterns from extant leather saddle covers, Connolly argued for a rigid wood frame topped by metal horn stiffeners and a leather casing. The problem with the solid wood frame solution is that it is heavy and there are stability issues.

A new study proposes a stuffed and padded structure rather than one of wood. The author first gathered information from 40 reenactors who ride on saddles that use the Connolly design. They confirmed, as Connolly had found, that the saddle works well for experienced riders at a walk, trot, canter and gallop (less so for inexperienced riders at a trot), but if you have to lean out of the saddle to use a weapon, stability plummets and constrains the range of motion.

Following up on these results, the author’s dissertation compared modern saddles of varying flap design (the part against which the rider’s thigh rests) and the flapless Roman saddle which utilises horns in front of and behind the rider on each corner of the saddle seat instead of stirrups. The fifteen participants in this follow-up project rode in four different saddle designs in walk, trot and canter, the Connolly saddle being one of these. […]

The Roman saddle compared favourably with the three modern saddles, but comments given by the participants of the saddle study referred more to the rigidity of the Connolly design rather than their ability to ride the horse. The main comment made was that the wooden side boards of the Connolly reconstruction prevented the riders from wrapping their leg around the horse and thereby influencing their stability.

Armed with this feedback, the study author made a saddle relying on flexible stuffing and padding for structure instead of wood. Inspired by 19th century California Vaquero saddles, the reconstructed Roman saddle was built with thatching straw stuffed into linen. The panels of the seat were made with pig skin; the horns with goat skin. The unwashed, lanolin-rich waterproof fleece of the Cotswold Lion, a sheep breed introduced to Britain by the Romans, was stuffed into the panels and horns.

Armed with this feedback, the study author made a saddle relying on flexible stuffing and padding for structure instead of wood. Inspired by 19th century California Vaquero saddles, the reconstructed Roman saddle was built with thatching straw stuffed into linen. The panels of the seat were made with pig skin; the horns with goat skin. The unwashed, lanolin-rich waterproof fleece of the Cotswold Lion, a sheep breed introduced to Britain by the Romans, was stuffed into the panels and horns.

The completed reconstruction saddle was inspected by a British Master Saddler and passed fit for form and function. This means that the saddle conformed to the principles of saddle design for the requirements of correct fit for the comfort of the horse. The saddle was then tested for rider comfort and utility on the mechanical horse in a comparison test with the Connolly saddle. A volunteer male rider of approximately 6ft in height, to satisfy Vegetius’ description of a cavalryman in Part 1 of his De re militari, rode in walk, trot and canter in each saddle.

It was noted that the contours of the new reconstruction’s panels were better at moulding themselves to the horse and there was no “bridging” of the panels, a feature to be avoided in modern saddle fitting. This bridging effect is where the panels do not conform to the horse’s back causing discomfort and riding problems. This bridging was present in the Connolly saddle and could only be rectified by adding a saddle pad with shims to level the saddle on the horse’s back. The rider also commented that the Connolly saddle held him in place like a cradle whereas the straw/fleece reconstruction did not fix him in place. The wooden horns of the Connolly saddle – which are known to break – were also uncomfortable after a period of cantering.

During the riding trials it was found that the new reconstruction’s horns were too flexible and highlighted the case for “stiffeners”, the bronze saddle horn covers found in the archaeological record. This was also noted when the rider adopted a light or half seat, that is rising out of the saddle from the strength of the thighs only as if making a sword or spear thrust. The requirement of bronze “stiffeners” to reinforce the wooden construction produced by Connolly has been questioned but it is clear from this reconstruction without wood that they would be necessary for the stability of the rider.

The new saddle construction weighs less than the Connolly saddle yet retains rigidity which is seen as a positive for the horse since it must also carry an armoured and armed rider. There is a need for further research to optimise the new reconstruction for girth placement and “stiffeners” before field trials can be conducted with live horses. A saddle cover has not yet been made to complete the reconstruction as the author is sourcing a blacksmith to manufacture “stiffeners” so that further experiments can be conducted.