A carved and inscribed ancient Greek marble plaque in the collection of the National Museums Scotland has been translated and published for the first time. It is a list of ephebic friends, close classmates who went through the ephebate in Athens, a year of rigorous military and civic training, during the reign of the Emperor Claudius (41-54 A.D.).

A carved and inscribed ancient Greek marble plaque in the collection of the National Museums Scotland has been translated and published for the first time. It is a list of ephebic friends, close classmates who went through the ephebate in Athens, a year of rigorous military and civic training, during the reign of the Emperor Claudius (41-54 A.D.).

Ephebic training began in the 4th century B.C. as a requirement for all young men eligible for admission as Attic citizens. If they were 18 years old of Attic parentage on both sides, the youths would be de jure citizens, but to actually exercise those rights (vote, be party to a lawsuit, attend the assembly), first they had to sign up for two years of military studies. The requirement was ultimately dropped, and by the 2nd century B.C., ephebic training was open to foreigners and the study of literature and philosophy was added to the curriculum. From around 39 A.D., anybody from anywhere who graduated from an ephebia was deemed an Attic citizen.

Lists of ephebic classmates have been found going back to the beginning of the program, but they reached peak popularity during the reign of Claudius with the proliferation of philoi lists, names of select ephebes who were particularly close classmates.

Lists of ephebic classmates have been found going back to the beginning of the program, but they reached peak popularity during the reign of Claudius with the proliferation of philoi lists, names of select ephebes who were particularly close classmates.

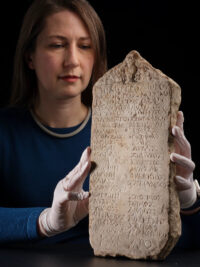

The inscription was published as part of the Attic Inscriptions in UK Collections (AIUK), an ambitious digitization project to add all ancient Attic inscriptions in UK collections and institution to the Attic Inscriptions Online (AIO) database. The stele’s precise origins are unknown. It was donated to the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland in 1887 by Scottish author and musician Alexander Wood Inglis, but there are no records explaining its previous history or how Inglis acquired it. AIUK researchers found a reference to the plaque in the National Museums Scotland catalogue and first thought it was a copy of a list from the same period now in the Ashmolean Museum in Oxford. When they retrieved it that it was a previously undocumented ephebic list.

Dr Peter Liddel, professor of Greek history and epigraphy at the University of Manchester, who led on the discovery, said: “Because of lockdown we were not able to travel to the museum until July 2021, and on seeing it we realised that this was not a copy of an already known inscription but it was a completely unique new discovery which had been in the storerooms of the NMS for a very long time, since the 1880s, and it listed a group of young men who called themselves co-ephebes or co-cadets and friends.

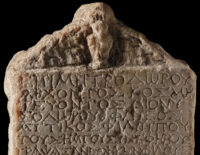

The top of the plaque is peaked and a worn relief believed to depict a small oil amphora of the type ephebes would have used in the school gymnasium. Under the relief the inscription begins:

The top of the plaque is peaked and a worn relief believed to depict a small oil amphora of the type ephebes would have used in the school gymnasium. Under the relief the inscription begins:

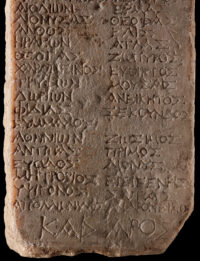

In the archonship of Metrodoros, when the superintendent was Dionysodoros (son of Dionysodoros) of Phlya, Attikos son of Philippos, having inscribed his own fellow ephebes (and) friends, dedicated (this).

The 31 names are inscribed in two columns under the dedication. Attikos’ select bros in the ephebate were Aiolion, Dionysas, Anthos, Herakon, Theogas, Charopeinos, Tryphon, Dorion, Phidias, Symmachos, Athenion, Antipas, Euodos, Metrobios, Hypsigonos, Apollonides, Hermas, Theophas, (H?)elis, Atlas, Zopyros, Euthiktos, Mousais, Aneiketos, Sekoundos, Zosimos, Primos, Dionys, Eisigenes, Sotas and Androneikos.

Dr. Liddel again:

“It turned out to be a list of the cadets for one particular year during the period 41-54 AD, the reign of Claudius, and it gives us new names, names we’d never come across before in ancient Greek, and it also gives us among the earliest evidence for non-citizens taking part in the ephebate in this period.

Several of the names are actually shortened versions (Theogas for Theogenes, Dionysas for Dionysodoros), conveying the lack of formality and camaraderie between the classmates. There appears to be a hierarchical element in the arrangement of names. Three of the young men at the top of the list are known from other inscriptions to have been the scions of prominent Attic families, and another one of the five (Dionysas, the second on the list) was the son of the superintendent.

The last name on the list wasn’t an ephebe at all. It was Caesar.

The word is in the genitive, signifying that the dedication was made in his reign, but also more broadly under his tutelage. In the Roman period, many of the ephebes’ activities emphasised veneration of the Roman emperor as a central part of Athenian identity.

That is a significant marker of the tectonic cultural shift from the origins of the ephebate as military training for young citizens of Attic city-states — direct civic engagement in the political structure of their native city transformed into elite schooling under the aegis of and beholden to the emperor in Rome.