Maritime archaeologists have discovered the remains of a 17th century trading vessel on the bed of the Trave River near the Baltic port city of Lübeck, Germany. The ship’s remains were first spotted in February 2020 during a routine survey of the Trave’s shipping channels when sonars detected an anomaly on the riverbed at a depth of 36 feet. Divers were finally able to explore the site in August 2021, and they alerted Lübeck cultural heritage authorities that they’d identified a likely shipwreck. Archaeologists from the Institute of Prehistoric and Protohistoric Archaeology at Kiel University were commissioned to examine the wreck site in detail in November 2021.

Maritime archaeologists have discovered the remains of a 17th century trading vessel on the bed of the Trave River near the Baltic port city of Lübeck, Germany. The ship’s remains were first spotted in February 2020 during a routine survey of the Trave’s shipping channels when sonars detected an anomaly on the riverbed at a depth of 36 feet. Divers were finally able to explore the site in August 2021, and they alerted Lübeck cultural heritage authorities that they’d identified a likely shipwreck. Archaeologists from the Institute of Prehistoric and Protohistoric Archaeology at Kiel University were commissioned to examine the wreck site in detail in November 2021.

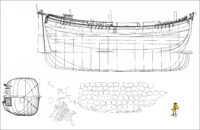

Over the last eight months, archaeologists have made 13 dives for a total of 464 minutes, photographing, filming and mapping all of the site. There were no cannons, so researchers were able to eliminate the possibility that it was a warship. They determined it was a sailing vessel carrying at least 150 large barrels of cargo. About 70 of them were found in their original location on the ship. The other 80 were adjacent to them. That means the ship sank straight down and stayed upright. It never listed or capsized.

The wooden planking was dated to around 1650, the late Hanseatic period when Lübeck was a center of maritime trade in northern Europe. This type of medium-sized sailing ship was a workhorse of the Baltic Sea trade network, but equivalent wrecks have only been found in the eastern Baltic Sea region. This is the first one found in the western Baltic.

The wooden planking was dated to around 1650, the late Hanseatic period when Lübeck was a center of maritime trade in northern Europe. This type of medium-sized sailing ship was a workhorse of the Baltic Sea trade network, but equivalent wrecks have only been found in the eastern Baltic Sea region. This is the first one found in the western Baltic.

The wood of the cargo barrels has rotted away, but happy archaeological coincidence, we know what they contained: lime, because it hardens to a rock-hard solid in contact with water, so while the barrels disintegrated, the cargo has survived for centuries. Lime was a key building material used to produce mortar and plaster in the Middle Ages and Early Modern era. The ship was probably loaded up with lime at a Scandinavian point of origin and then sailed for Lübeck but didn’t quite make it.

The wreck was found in the middle of the canal at a bend in the river which was notoriously challenging to navigate. It’s not clear what caused the vessel to sink. Archaeologists believe it may have run aground at the ben and sprang a leak. It sank on an even keel (probably thanks to being so effectively ballasted by its heavy lime cargo) and landed upright on the riverbed.

The remains of the ship and cargo are under threat today from erosion and shipworm. It is only a matter of time before it disappears completely, so Kiel University researchers are working the City of Lübeck to protect the wreck. The default posture is in situ preservation whenever possible, but with the rapid deterioration of this wreck, experts are looking at the possibility of salvaging the timbers and cargo and preserving them on terra firma.

Raising the ship from the riverbed will give archaeologists a chance to fully investigate the hull and its construction, and perhaps identify its origin. “The salvage will probably also uncover previously unknown parts of the wreck that are still hidden in the sediment,” [the head of Lübeck’s archaeology department Manfred] Schneider said, such as rooms for the ship’s crew in the stern that may still hold everyday objects from the 17th century.

Although Lübeck was a center for Baltic trade during the Hanseatic period, very few authentic maritime objects from that time had survived, Schneider said, so the discovery of almost an entire ship from this era is remarkable. “We have something like a time capsule that transmits everything that was on board at that moment,” he said. “It throws a spotlight on the trade routes and transport options at the end of the Hanseatic period.”

Here is raw video taken of the wreck during a dive:

what a great find . I love Lübeck and have spent some wonderful time wondering around the city . The Schiffersgeselshaft is particularly wonderful . It is a still functioning restaurant which has been in existence since at least the 17 the century and is decorated with ship models made by sailors when they visited the port the dining room has booths which were reserved for sailors from different ports and they could come and meet up and eat and be merry . Just wonderful. The worn away seats and the patina of such an ancient place are just wonderful.

Hello Eunice . I have been there too . Its wonderful . what is even more amazing is that My name is Cassuben and my mothers name is Eunice Cassuben . We never thought to find another person of that name

The “Schiffergesellschaft” also harbours a real Inuit kayak from 1605 that allegedly had been “picked-up” by the Danish.

However, it seems as if the seafaring route to Europe had already been discovered by them 2000 years ago, and maybe this also explains, why there was an “India” expected in the West.

Contrastingly, the Periplus of the Erythraean Sea had been known to the Romans.

However…

When, according to Pliny the Elder, Quintus Metellus Celer had been the Roman proconsul in Gallia, it seems, the chieftain of the Suebi people sent him as a “gift” (“donum”) a bunch of “Indians” that had been washed ashore in Germany as traders (“commercii causa navigantes”). Similar kayaks later seem to have ended up in places like Ireland or Scotland.

:hattip:

————-

“idem Nepos de septentrionali circuitu tradit Quinto Metello Celeri, Afrani in consulatu collegae, sed tum Galliae proconsuli, Indos a rege Sueborum dono datos, qui ex India commercii causa navigantes tempestatibus essent in Germaniam abrepti. sic maria circumfusa undique dividuo globo partem orbis auferunt nobis, nec inde huc nec hinc illo pervio tractu. quae contemplatio apta detegendae mortalium vanitati poscere videtur, ut totum hoc, quicquid est, in quo singulis nihil satis est, ceu subiectum oculis quantum sit ostendam.”

————-